#16,547

Fifteen years ago avian flu - primarily Asian H5N1 - was viewed as a plausible pandemic threat as it spread globally via migratory birds, causing sporadic human infections and occasional larger outbreaks. The virus killed roughly 50% known humans infected, and sparked the first serious round of pandemic prep in the first decade of the 21st century.

By 2013, H5N1 appeared on the decline in much of the world, but it was suddenly joined by a serious contender; H7N9 - which would spark 5 significant waves of human infection in China before it was brought under control in 2017 using a new H5+H7 poultry vaccine.

Over 2013-2014, we saw a general resurgence in avian flu, with the emergence of H10N8 in China, H5N8 in South Korea (which spread globally in 2015 and has reassorted into various H5Nx subtypes), H6N1 in Taiwan, along with a short list of other H7Nx viruses (H7N2, H7N4, etc.).

2015 saw the last major H5N1 epidemic, in Egypt (see EID Dispatch: Increased Number Of Human H5N1 Infection – Egypt, 2014-15), but the following year (2016), we saw major reassortment in H5N8 roll across Europe, sparking the worst avian epizootic (to that point) on record.

While HPAI H5N8 clade 2.3.4.4b wasn't viewed as a serious zoonotic threat, it was suddenly more pathogenic in wild birds, and was spinning off into new subtypes (H5N1, H5N3, H5N5, etc.).

After a 30 month lull between 2017 to 2020, we've seen the return of avian HPAI H5 epizootics to Europe and Asia, this year in dominated by an HPAI H5N1 virus. Unlike its Asian counterpart, until a year ago, Eurasian H5N1 wasn't considered a zoonotic threat.

But over the past 12 months we've seen sporadic reports of mild human infection with this HPAI lineage, including 7 cases in Russia, cases in Nigeria, and last month a human infection in the UK (see WHO DON & Risk Assessment On Human H5 Infection In the UK).

While currently posing nowhere near the human threat of the old Asian H5N1, or China's current H5N6 virus, the Eurasian H5Nx virus continues to take baby steps towards better adaptation to mammals (see Netherlands DWHC Reports another Mammal (Polecat) Infected With H5N1), and that is a concern.

And this all comes as the virus continues to spread across Europe, Asia, Africa, the Middle East - and over the past few weeks - has turned up in North America for the first time in nearly 6 years.

Even without its potential to evolve into a bigger human threat, HPAI H5 can devastate poultry holdings, and kill off large populations of wild and migratory birds. We're we not in a coronavirus pandemic, the HPAI epizootics in Europe and Asia would undoubtedly be getting a lot more attention.

So today a roundup of recent reports from the Eurosurveillance Journal, DEFRA, the USDA, and Canada's CFIA on the progress of HPAI H5 in North America, and around the world.

First, from Eurosurveillance, a detailed report on the UK's first human H5 infection by the Eurasian lineage. A link and excerpt follow:

Rapid communication Open Access

A case of avian influenza A(H5N1) in England, January 2022

Isabel Oliver1 , Jonathan Roberts2 , Colin S Brown1 , Alexander MP Byrne3 , Dominic Mellon2 , Rowena DE Hansen3 , Ashley C Banyard3 , Joe James3 , Matthew Donati2 , Robert Porter4 , Joanna Ellis1 , Jade Cogdale1 , Angie Lackenby1 , Meera Chand1 , Gavin Dabrera1 , Ian H Brown3 , Maria Zambon1

We present a case report of the first confirmed human case of avian influenza A(H5N1) in England in January 2022 following identification of the strain in a duck flock kept at their residence. We describe the clinical epidemiological and virological aspects, and discuss the importance of surveillance through an asymptomatic testing programme.

An outbreak of high pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 was confirmed by the United Kingdom (UK) chief veterinary officer in a flock of ca 125 Muscovy ducks in a domestic setting in South West England on 22 December 2021. After the death of one bird on 18 December, followed by additional deaths and clinical signs of illness in the flock on 20 December, 20 Muscovy ducks were sampled on 21 December and samples submitted to the National Reference Laboratory at the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), Weybridge, UK with 19 live birds testing positive for H5N1 HPAI virus.

(SNIP)

Discussion

We report the first human case of avian influenza A(H5N1) in Europe. Although transmission from birds to humans is rare, there is a risk that these viruses may adapt and become able to infect and gain the ability to spread from person to person, therefore, early identification of human infection is of great public health importance.

In the context of a high prevalence of infection in birds in England, in 2021 UKHSA strengthened its surveillance to include testing of asymptomatic, potentially exposed contacts in addition to those who report symptoms following a potential exposure event. The aim of the asymptomatic testing programme is to ensure timely and effective detection of any possible case of transmission to humans. The programme will also provide intelligence to help refine public health risk assessment and facilitate case and situation management, given these recent changes in avian influenza epidemiology. This case reported here, confirmed by PCR testing followed by WGS, was detected through this testing programme but uptake was low among the case’s contacts who used PPE. The experience from this case will be incorporated into learning for future asymptomatic swabbing programmes in Great Britain.

The wider public health risk from this particular case was assessed to be very low. The affected individual remained asymptomatic throughout the event. Virological investigations indicated low infectivity and the individual reported very limited contact with other people. Importantly, the circumstances regarding exposure to birds were unusual, with a high degree of close contact with a large number of infected birds and a virus-contaminated enclosed domestic environment which resulted in infection. The spill-over infection to the human contact did not lead to any detected genetic changes in the virus that might be associated with increased zoonotic risk. This case demonstrates the increased risk posed by this kind of close contact but does not change the overall assessment that the risk to the general public from avian influenza virus remains very low.

This case reported no symptoms at any point in time during the event. Seroprevalence studies suggest that subclinical and clinically mild human A(H5N1) virus infections are uncommon [10]. Individuals may have immunity because of prior exposure, or prompt administration of prophylactic antiviral drugs could have tempered disease progression. Focussing testing on people who develop symptoms consistent with influenza will miss some infections, with consequent risk to public health. Testing asymptomatic people accompanied with active surveillance of individuals following a high-risk exposure to the virus without any PPE protection is recommended. Such investigations increase our knowledge of the zoonotic risk posed by influenza A viruses and provide important evidence help strengthen One Health responses, particularly given the unusual infection pressure in avian populations and extensive global spread of this particular strain of H5N1.

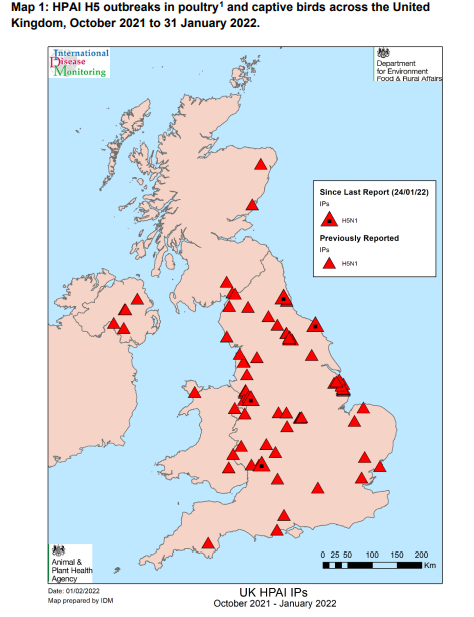

The UK's DEFRA has also released a new weekly update on their record-breaking HPAI H5 epizootic, which began last fall, along with a summary of avian flu activity across Europe.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in the UK and Europe

31 January 2022 Ref: VITT/1200

HPAI in the UK and Europe Disease Report

Since our last outbreak assessment on 24 January 2022, there continue to be reports of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5 both in Europe and in the United Kingdom (UK). This includes four further outbreaks in domestic poultry and captive birds in the UK.

There have been a further four confirmed outbreaks in Great Britain (GB) of HPAI H5N1 in domestic poultry and captive birds since our last assessment, all of which have been in England. One outbreak has affected a commercial turkey premises in Cheshire, while the other three outbreaks have occurred in a backyard premises in Gloucestershire, a city farm in Tyne and Wear, and a wildlife rescue centre in North Yorkshire. There have been no further HPAI H5N1 outbreaks in Northern Ireland since 24 January 2022 (DAERA 2022).

According to the OIE, HPAI H5N1 reports have continued in Europe over the past week. Since 24 January 2022, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands and Poland have reported further outbreaks of HPAI H5N1, Bulgaria has reported further outbreaks of HPAI H5 and Moldova has reported an outbreak of H5N1 in domestic poultry for the first time this HPAI season.

Wild bird HPAI H5 cases continue to be reported in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, the Republic of Ireland, Russia, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden. The highest number of cases was reported in Germany (71) which included a case of HPAI H5N3.

Moving over to this side of the pond, Canada's CFIA has published an update on the detection of H5N1 in Nova Scotia, which I reported on last Tuesday (see Canada: Media Reporting Another H5N1 Detection (Nova Scotia)).

Detection of high pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) in Newfoundland and Labrador 2021 and Nova Scotia 2022

Update on current investigation

February 3, 2022

On February 1, 2022, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) confirmed the presence of high pathogenic avian influenza (AI), subtype H5N1, in a backyard flock in central Nova Scotia. This backyard flock does not produce birds for sale and is considered a non-poultry detection.

This follows several confirmed detections of the same strain of AI in wild birds in Newfoundland and more recently in a wild goose found in central Nova Scotia.

As per the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) guidance, Canada's 'free from AI' status remains in place.

While these additional detections should have no impact on trade, this situation serves as a strong reminder that AI is spreading across the globe in wild birds as they migrate to and from Canada, and that anyone with farm animals, including birds, should practice good biosecurity habits to protect them from animal diseases.

2022 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza

Last Modified: Feb 3, 2022

Through its ongoing wild bird surveillance program, APHIS collects and tests large numbers of samples from wild birds in the North American flyways. It is not uncommon to detect avian influenza in wild birds, as these viruses circulate freely in those populations without the birds appearing sick. The recent detections of this strain of Eurasian H5 avian influenza in wild birds serve as an early warning system for bird owners in the U.S. to review and stay vigilant about their biosecurity practices to protect poultry and pet birds from avian influenza.

While the Eurasian HPAI H5 virus is admittedly still a few mutations short of posing a serious public health threat, it is already wreaking havoc with poultry producers in Europe, and Asia, and - for the first time since 2016 - is knocking on North America's door.