Six weeks ago, in UKHSA Reports 2 (Travel Related) Lassa Fever Cases - 1 Additional Suspected, we looked at the initial report of a `travel related' family cluster of Lassa fever cases reported in the UK.

While Lassa is classified as a Viral Hemorrhagic Fever - and can be deadly - it is generally not considered to be as serious as many other VHFs (e.g. Ebola, Marburg, Nipah, CCHF, ect.).

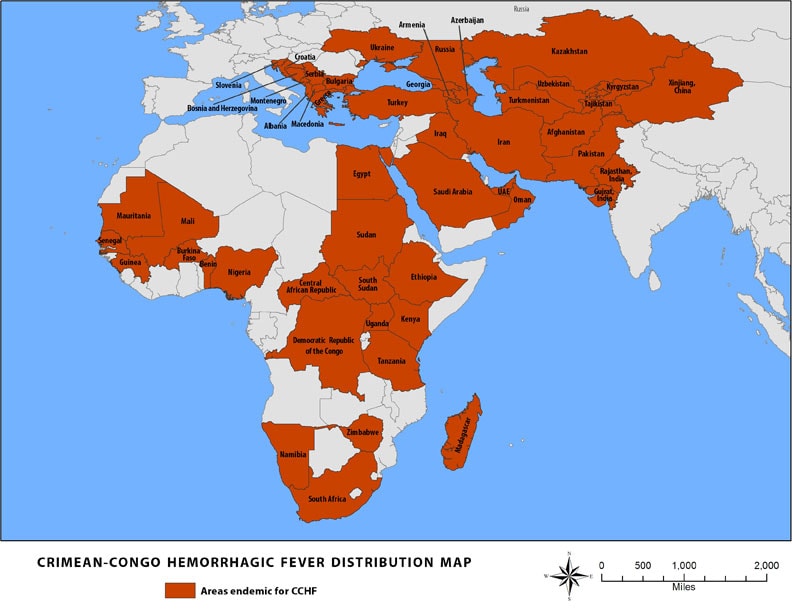

Today the UK reports another imported VHF - this time involving a more serious Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHF) - diagnosed in a woman who had recently traveled to Central Asia. Per usual, the UKHSA is providing few details, but we'll undoubtedly learn more in the days ahead.

Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever case identified in England, following travel to Central Asia

Latest updates on a case of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever identified in England.

From: UK Health Security Agency

Published 25 March 2022

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) can confirm that a case of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF) has been confirmed in England. The woman had recently travelled to Central Asia.

CCHF is a viral disease usually transmitted by ticks and livestock animals in countries where the disease is endemic.

The patient was diagnosed at Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and is receiving specialist care at the Royal Free Hospital in London.

Dr Susan Hopkins, Chief Medical Advisor at UKHSA said:

It’s important to be aware that CCHF is usually spread by tick bites in countries where the disease is endemic, it does not spread easily between people and the overall risk to the public is very low.

We are working with NHS EI to contact the individuals who have had close contact with the case prior to confirmation of their infection, to assess them as necessary and provide advice.

UKHSA and the NHS have well established and robust infection control procedures for dealing with cases of imported infectious disease and these will be strictly followed.

Dr Sir Michael Jacobs, consultant in infectious diseases at the Royal Free London, said:

The Royal Free Hospital is a specialist centre for treating patients with viral infections such as CCHF. Our high level isolation unit is run by an expert team of doctors, nurses, therapists and laboratory staff and is designed to ensure we can safely treat patients with these kind of infections.

Prior to this case, there have been 2 cases of CCHF imported to the UK, in 2012 and one in 2014. There was no evidence of onward transmission from either of these cases.

The principal carriers of CCHF are Hyalomma ticks, these are not established in the UK and the virus has never been detected here in a tick.

People living in or visiting endemic areas should use personal protective measures to avoid contact with ticks, including:

- avoiding areas where ticks are abundant at times when they are active

- using tick repellents

- checking clothing and skin carefully for ticks

While it is possible for this Hemorrhagic virus to be transmitted from human-to-human, the risk is relatively low. The CDC describes the transmission of CCHF on their VHF website.

Ixodid (hard) ticks, especially those of the genus, Hyalomma, are both a reservoir and a vector for the CCHF virus. Numerous wild and domestic animals, such as cattle, goats, sheep and hares, serve as amplifying hosts for the virus. Transmission to humans occurs through contact with infected ticks or animal blood. CCHF can be transmitted from one infected human to another by contact with infectious blood or body fluids. Documented spread of CCHF has also occurred in hospitals due to improper sterilization of medical equipment, reuse of injection needles, and contamination of medical supplies.

One of the realities of life in this third decade of the 21st century is that the world is vastly smaller than was a couple of generations ago. Vast oceans and extended travel times no longer offer us much protection, and there is no technological shield that we can erect that would keep an emerging pandemic virus out.

Most viral infections have a 2 to 7 day incubation period, giving an infected traveler a fairly long asymptomatic `window' for travel. As a result, over the past decade we've seen a growing number of exotic, often highly dangerous diseases being carried to new regions by travelers around the globe.

As we've seen with MERS-CoV, Monkeypox, H5N1, and Ebola - most of these introductions fail to take root - but the rapid global spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in early 2020 illustrates how quickly a highly contagious disease can conquer the world.

While not quite as dramatic, over the past couple of decades we've seen a number of high-impact geographic expansions of exotic diseases due to infected travelers, including.

- The arrival of West Nile Virus in New York in 1999

- In 2003 SARS spread from China, to Canada, and then on to more than a dozen more countries.

- The reintroduction of Dengue to South Florida in 2009

- The introduction of Chikungunya to the Caribbean in the fall of 2013

- The spread of Zika to South America in 2015

Which makes the funding and support of international public health initiatives like the World Health Organization, animal health initiatives like the FAO and OIE , and disease surveillance grows more important with every passing year.The place to try to stop the next pandemic is not at the airport gate, but in the places around the world where they are likely to emerge.