#16,813

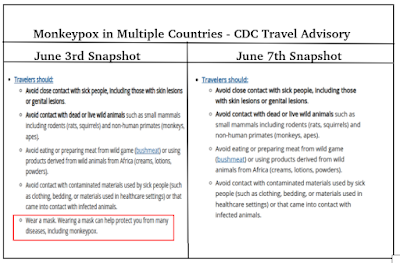

Earlier this week the CDC abruptly removed their `mask recommendation' from their Monkeypox travel advisory (see comparison above), and has recently changed their Infection Prevention and Control of Monkeypox in Healthcare Settings guidance, which on May 21st, called for:

. . . . standard, contact, and droplet precautions, the isolation of all suspected Monkeypox cases, and also warns of the theoretical risk of airborne transmission, and advises HCWs use fit-tested N95 respiratory protection.

Isolate patients suspected of having monkeypox in a negative air pressure room as soon as possible.

The new guidance (minus the above graphic), now only calls for a private room (no special air handling required) and de-emphasizes the potential airborne spread of Monkeypox, leaving some people delighted and others scratching their heads.

Changes in guidance are common, particularly in the early days of an outbreak of a novel or exotic disease. As more is learned, often less draconian measures can be safely recommended.

But as we saw with COVID-19, sometimes the opposite occurs. Hence we saw the 180 degree turnaround by the CDC on the public's wearing of face covers in April of 2020. It would take months before COVID's airborne transmissibility would be accepted by major public health entities.

We are still learning about the spread, and clinical presentation, of Monkeypox (see IJID: Increased Outbreaks of Monkeypox Highlight Gaps in Actual Disease Burden in Sub-Saharan Africa), and it is possible that over time we may find that some of our current assumptions are wrong.

With the caveat that as more is learned, changes may be required, yesterday the CDC issued the following press release providing their current understanding of how the Monkeypox virus is transmitted.

CDC Monkeypox Response: Transmission

Media Statement

For Immediate release: Thursday, June 9, 2022

Contact: Media Relations

(404) 639-3286

Monkeypox virus is a completely different virus than the viruses that cause COVID-19 or measles. It is not known to linger in the air and is not transmitted during short periods of shared airspace. Monkeypox spreads through direct contact with body fluids or sores on the body of someone who has monkeypox, or with direct contact with materials that have touched body fluids or sores, such as clothing or linens. It may also spread through respiratory secretions when people have close, face-to-face contact.

In the current monkeypox outbreak, we know that those with disease generally describe close, sustained physical contact with other people who are infected with the virus. We continue to study other possible modes of transmission, such as through semen.

Prior studies of monkeypox outbreaks show that spread of monkeypox virus by respiratory secretions appears uncommon. Most cases of monkeypox report close contact with an infectious person. While we do not know with certainty what role direct physical contact has versus the role of respiratory secretions, in instances where people who have monkeypox have travelled on airplanes, no known cases of monkeypox occurred in people seated around them, even on long international flights.

There are important differences between airborne transmission and transmission via respiratory secretions. Airborne transmission occurs when small virus particles become suspended in the air and can stay there for periods of time. These particles can spread on air currents, or sometimes even infect people who enter a room after the infected person has left. In contrast, monkeypox may be found in droplets like saliva or respiratory secretions that drop out of the air quickly. Long range (e.g., airborne) transmission of monkeypox has not been reported.

CDC currently recommends that people infected with monkeypox wear a mask if they must be around others in their homes if close, face-to-face contact is likely. In a healthcare setting, a patient with suspected or confirmed monkeypox infection should be placed in a single-person room; special air handling is not required. Any procedures likely to spread oral secretions (such as intubation and extubation) should be performed in an airborne infection isolation room.

Examples where monkeypox can spread:

As we learn more about this outbreak, we will update recommendations to help people protect themselves and to prevent the spread of monkeypox.

- No: Casual conversations. Walking by someone with monkeypox in a grocery store. Touching items like doorknobs.

- Yes: Direct skin-skin contact with rash lesions. Sexual/intimate contact. Kissing while a person is infected.

- Yes: Living in a house and sharing a bed with someone. Sharing towels or unwashed clothing.

- Yes: Respiratory secretions through face-to-face interactions (the type that mainly happen when living with someone or caring for someone who has monkeypox).

- Maybe/Still learning: Contact with semen or vaginal fluids.

- Unknown/Still learning: Contact with people who are infected with monkeypox but have no symptoms (We think people with symptoms are most likely associated with spread, but some people may have very mild illness and not know they are infected).

For more information about the monkeypox outbreak, visit: Transmission | Monkeypox | Poxvirus | CDC.