$16,909

Since early April (see UK HSA: Investigating An Unusual Increase In Hepatitis In Children) we've been following the detection of a spike in acute hepatitis in children of unknown origin - first reported in the UK - and now reported in nearly 3 dozen countries around the world.

Yesterday the UK released an update, and their 4th Technical Briefing on this outbreak. While the exact cause remains unknown, both focus on potential link to Adenovirus Associated Virus 2 (AAV2) for this outbreak.

Since AAV2 by itself is normally a benign virus in humans, its role in the disease remains unknown, but is assumed to be part of a multi-faceted process.

First the update from the UK HSA, followed by a link and some excerpts from the 56-page technical briefing.The CDC is also closely investigating cases here in the United States (see CDC website Children with Acute Hepatitis of Unknown Cause), and currently cites 354 PUIs (persons under investigation) across 43 states and jurisdictions.

Hepatitis (liver inflammation) cases in children – latest updates

Regular UKHSA updates on the ongoing investigation into higher than usual rates of liver inflammation (hepatitis) in children across the UK.

From: UK Health Security Agency Published 6 April 2022Last updated 28 July 2022 — See all updates

Latest

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) has published its fourth technical briefing, detailing investigations into a rise in cases of sudden onset hepatitis in children.

As of 19 July, there have been 270 confirmed cases of hepatitis in children aged 10 and under. Of these children, 15 have received a liver transplant; none has died. The rate at which new cases are reported has now declined.

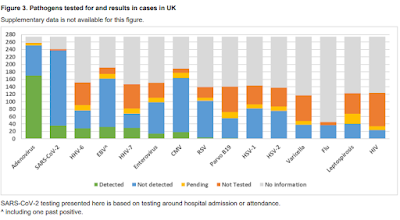

The technical briefing looks at 274 confirmed and possible cases up until 4 July. Adenovirus remains the most frequently detected potential virus in cases. Amongst 274 UK cases, 258 have been tested for adenovirus, of which 170 (65.9%) had adenovirus detected.

A UK-wide case-control study has also found a strong association between adenovirus infection and this cluster of cases. Routine surveillance data shows particular increases in adenovirus detection and positivity in laboratory reports in young children before and after those affected by the outbreak reported symptoms. Similar increases were not seen in older children or adults.

The technical briefing includes details of a study by the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research (CVR) and the Royal Hospital for Children in Glasgow. It is in partnership with Public Health Scotland and International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infections Consortium (ISARIC) WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol UK (CCP-UK) – and a second studying cases from across all 4 UK nations at Great Ormond Street Hospital and the UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health (UCL GOS ICH), in partnership with UKHSA.

The studies used metagenomics, studying samples taken from those affected, to take an unbiased approach to seeking other viruses that may be involved in the cause of the outbreak. In addition to supporting the finding on adenovirus, both studies detected adenovirus associated virus 2 (AAV2) in the majority of cases studied, but absent (or at low levels) in samples taken from people unaffected by the outbreak as part of the study (known as controls). AAV2 does not typically cause illness itself and needs a ‘helper’ virus to be able to divide in the body. There are also some early findings which suggest that differences in people’s immune systems could potentially be playing a role. At the moment, it is too early to say how these findings interact and which ones are significant in context of the outbreak.

The role that coronavirus (COVID-19) may have played has been further investigated – 4.4% of cases were positive for SARS-CoV2 in the 2 weeks leading up to hospital admission, compared to 4% in a random age-matched sample of A&E admissions. To understand whether prior COVID-19 infection was playing a role, cases who had COVID-19 positive tests at any point prior to hepatitis symptoms were studied. This found that 11.9% cases had a COVID-19 positive test, compared to 15.6% in the random sample – the difference is not statistically significant. In addition, analysis of blood samples from cases revealed no significant difference in the presence of SARS-CoV2 antibodies in cases compared to age-matched NHS patient controls. This evidence, in conjunction with data published by researchers at the University of Glasgow and University College London, suggests that the rise in hepatitis cases is unlikely to be linked to prior COVID-19 infection.

Dr Meera Chand, Director of Clinical and Emerging Infections, said:

Untangling the cause of the rise in childhood hepatitis cases observed in 2022 is complex and multiple strands of investigation point towards the possibility that several different factors have combined to cause severe illness in some children.

It’s important to remember that it’s very rare for a child to develop hepatitis and new cases associated with this outbreak have now declined. UKHSA continues to work with academic and international partners to understand why this cluster occurred and any future risks.

Technical briefing 4

26 July 2022

SummaryThis briefing is produced to share data useful to other public health investigators and academic partners undertaking related work. Although a detailed clinical case review is also taking place, that data is not shared here as, given the small number of cases, there are some risks to confidentiality.CasesAs of 4 July 2022, there have been 274 cases of acute non-A to E hepatitis with serum transaminases greater than 500 IU/L identified in children aged under 16 years old in the UK, since 1 January 2022. This is the result of an active case finding investigation commencing in April which identified retrospective as well as prospective cases. Fifteen cases have received a liver transplant; no cases resident in the UK have died.While new cases continue to be identified across the UK, including cases that meet the case definition and reported cases that are pending classification, there is an overall decline in rates of cases, even allowing for reporting lags.Cases pending classification are usually those in which laboratory testing to rule out known causes of hepatitis is incomplete.Associated pathogens and proposed hypothesesAdenovirus remains the most frequently detected potential pathogen in cases. Amongst 274 UK cases, 258 have been tested for adenovirus, of which 170 (65.9%) had adenovirus detected.In a UK-wide frequency matched case-control study, multivariable regression analyses with 74 cases and 225 controls indicate that cases have statistically significant higher odds of concomitant adenovirus infection compared to controls (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 35.27, 95% CI 15.23 to 81.68). This finding is supported by routine surveillance data, in particular increases in adenovirus detection and positivity in laboratory reports in young children (but not older children and adults) preceding and corresponding to the alert of the clinical phenomenon.SARS-CoV-2 has been detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing around the time of admission in 36 out of 237 (15.2%) UK cases with available results, although in English cases only the proportion positive was lower (9.9%). To further explore the potential role of concurrent or preceding SARS-CoV-2 infection in England, analyses comparing positivity in cases to community controls in the same time period were undertaken. A comparison between cases and a random age-matched sample of emergency department admissions in children did not show any significant differences in PCR positivity. Similarly, the weekly swab positivity in cases was consistent with NHS Pillar 1 (testing based on clinical need) and community rates from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Coronavirus Infection Survey. Furthermore, on comparing Acute hepatitis of unknown aetiology: technical briefing 4 6 nucleocapsid or spike protein antibody seropositivity to SARS-CoV-2 in cases to NHS agegroup matched community controls, no significant differences were found.While the association between adenovirus infection and cases is helpful in guiding further investigations into the aetiology, the lack of apparent direct toxic effect of the virus on liver tissue and other results suggests this is part of a multiple-step process. Other hypotheses are being investigated, including exposure to environmental toxins (for example, mycotoxins found in food), other viruses, and genetic factors as other ‘triggers’ for this phenomenon.As mentioned in the previous technical briefings, analysis of a small number of blood and liver samples with metagenomics showed a strong association with adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV2). Their role in this acute hepatitis syndrome remains unclear and investigations continue. UKHSA and Public Health Scotland have collaborated with academic partners to take forward this part of the investigation.