#17,008

Antivirals - like antibiotics and antifungals - have an Achilles' heel. Over time, and if frequently used enough, the pathogens (viruses, bacteria, or fungi) they were designed to suppress can evolve or mutate enough to render them ineffective.

When I began flu blogging in 2005, Amantadine - which had been around since the 1960s - was still being used as an influenza antiviral, and was favored by many countries over the newer, and more expensive Tamiflu (tm) (Oseltamivir) developed in 1996.Sometimes that process takes decades. Sometimes far less time.

But by late 2005 Amantadine began to lose its effectiveness against the H3N2 seasonal flu virus and some strains of the H5N1 bird flu, possibly as a result of the prophylactic use of the drug by Chinese poultry farmers who routinely included it in their chicken feed for several years.

In January of 2006 the CDC issued a warning to doctors not to rely on Amantadine or Rimantadine to treat influenza. Tamiflu (Oseltamivir), while far more expensive, became the new treatment standard.

But within two years seasonal H1N1 began to show growing resistance to Tamiflu as well (although H3N2 remained sensitive). By the spring of 2009 - in the space of just about a year – seasonal H1N1 had gone from almost 100% sensitive to the drug to nearly 100% resistant.

While it seemed as if antiviral crisis was inevitable, in a Deus Ex Machina moment a new swine-origin H1N1 virus - one that happened to be sensitive to Oseltamivir - swooped in as a pandemic strain in the spring of 2009, supplanting the older resistant H1N1 virus.

Oseltamivir remains effective against most strains of influenza, but in 2018 the FDA approved Xofluza : A New Class Of Influenza Antiviral, giving us a much needed backup.

Currently there are no FDA approved antivirals for use against Monkeypox, however one experimental drug - TPOXX (tm) (aka tecovirimat) - is available for use during this emergency. The FDA explains:

Currently, there are no FDA-approved treatments for monkeypox; however, TPOXX (tecovirimat), an antiviral medication, is being made available through a randomized controlled clinical trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and also through the CDC under an FDA authority called Expanded Access, or “compassionate use.”

The FDA goes on to say:

TPOXX as a treatment for monkeypox infections:

The safety and efficacy of TPOXX to treat monkeypox in humans has not been established. Conducting randomized, controlled trials to assess TPOXX’s safety and efficacy in humans with monkeypox infections is essential. We don’t currently know if TPOXX will be beneficial in treating patients with monkeypox, since drugs that are effective in animal studies are not always effective in humans.

On September 8, 2022, NIAID opened a randomized, controlled clinical trial to assess the safety and efficacy of TPOXX for the treatment of monkeypox infection. Health care providers should encourage their patients with monkeypox infection to be evaluated for enrollment in this trial. For patients for whom enrollment in this trial is not feasible (e.g., a clinical trial site is not geographically accessible), use of tecovirimat under CDC’s expanded access protocol should be consistent with applicable guidelines for tecovirimat use.

Yesterday, the FDA published a statement on the potential for this new antiviral to be thwarted by mutations in the Monkeypox virus.

Viruses can change over time. Sometimes these changes make antiviral drugs less effective at combating the virus they are targeting, meaning those drugs won’t work as well or might not work at all.

TPOXX works by inhibiting a viral protein, called VP37, that all orthopoxviruses (e.g., smallpox virus, monkeypox virus, vaccinia virus) share. However, as noted in the drug label, TPOXX has a low barrier to viral resistance. This means small changes to the VP37 protein could have a large impact on the antiviral activity of TPOXX.

CDC scientists are actively monitoring for changes in the monkeypox virus that could make the virus less susceptible to TPOXX. Because of the potential for the virus to become resistant to TPOXX, it is important the drug be used in a judicious manner.

Patients should enroll in NIAID’s randomized, controlled clinical trial when feasible to facilitate assessment of the safety, efficacy, and resistance profile of TPOXX. For patients for whom enrollment in a randomized clinical trial is not feasible (e.g., a clinical trial site is not geographically accessible), use of TPOXX under CDC’s expanded access protocol should be consistent with applicable guidelines for TPOXX use.

Information for the Scientific Community:

On September 12, 2022, the FDA released additional information in publicly posted reviews supporting approval of the new drug application for tecovirimat to describe specific changes in the VP37 proteins of orthopoxviruses (e.g., vaccinia virus and monkeypox virus) that are associated with tecovirimat drug resistance.

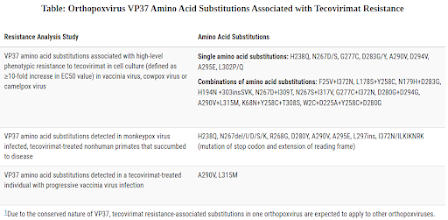

As described in the FDA reviews, multiple independent studies characterized tecovirimat resistance development in orthopoxviruses in cell culture studies, in animal studies, and in an anecdotal human case of progressive vaccinia. These studies identified several genetic pathways for orthopoxviruses to become resistant to tecovirimat, which involves the emergence of amino acid substitutions in the viral VP37 drug target (see Table below). Many of the resistance pathways require only a single amino acid change in VP37 to cause a substantial reduction in tecovirimat antiviral activity.

Collectively, these studies indicate tecovirimat has a low barrier to resistance, and this must be considered in the context of the current monkeypox public health emergency because there is a risk that tecovirimat resistant virus could emerge and possibly spread.

The FDA is releasing this information to aid the scientific community’s genomic sequencing efforts to support national surveillance of the current monkeypox virus outbreak in the U.S. The FDA believes releasing this additional information will further facilitate the ability to monitor for the development and spread of tecovirimat-resistant virus and therefore is important in promoting public health.

Granted, it may not be inevitable that Monkeypox will evolve to evade TPOXX (tm), but it is obviously a legitimate concern. Although it can take a decade or longer to develop and test a new therapeutic, it can be rendered obsolete practically overnight by the `right' mutation.

Each year we draw a little closer to a dreaded, but highly plausible `post-antibiotic era', where even common infections become resistant to most antibiotics, and something as simple as a scraped knee, or elective surgery, could be deadly.Whether it is vaccines, antibiotics, or antivirals, we are engaged in an endless `arms race' with countless thousands of constantly evolving pathogens whose very survival depends on evading our medical armamentarium.