#17,009

The recent spillover of a novel avian H3N8 virus into 2 children in China last spring quickly attracted the global attention of scientists , as H3N8 has been on our radar as a virus with human pandemic potential for quite some time.

H3N8 remains a plausible cause of a global influenza pandemic that spread out of Russia in 1889-1900, although some researchers now suspect a novel coronavirus instead.

But over the past 50 years we've also seen it jump to horses (in the 1960s), and then to dogs in 2004 (see EID Journal article Influenza A Virus (H3N8) in Dogs with Respiratory Disease, Florida), and more recently to marine mammals (see mBio: A Mammalian Adapted H3N8 In Seals).

On Wednesday The Lancet published another review - this time focusing on the second, milder case - reported in a 4 year-old last May in Hunan province. I've only reproduced the summary from what is a much larger, and highly detailed, report.

Follow the link to read it in its entirety. I'll have a brief postscript after the break.

Rengui Yang, BS * Prof Honglei Sun, PhD * Prof Feng Gao, PhD * Kaiwei Luo, MD * Zheng Huang, MD * Qi Tong, PhD et al.

Open Access Published:September 14, 2022 DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00192-6

Summary

Background

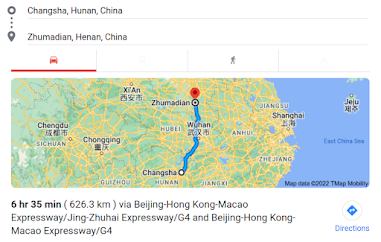

The H3N8 avian influenza virus (AIV) has been circulating in wild birds, with occasional interspecies transmission to mammals. The first human infection of H3N8 subtype occurred in Henan Province, China, in April, 2022. We aimed to investigate clinical, epidemiological, and virological data related to a second case identified soon afterwards in Hunan Province, China.

Methods

We analysed clinical, epidemiological, and virological data for a 5-year-old boy diagnosed with H3N8 AIV infection in May, 2022, during influenza-like illness surveillance in Changsha City, Hunan Province, China. H3N8 virus strains from chicken flocks from January, 2021, to April, 2022, were retrospectively investigated in China. The genomes of the viruses were sequenced for phylogenetic analysis of all the eight gene segments. We evaluated the receptor-binding properties of the H3N8 viruses by using a solid-phase binding assay. We used sequence alignment and homology-modelling methods to study the effect of specific mutations on the human receptor-binding properties. We also conducted serological surveillance to detect the H3N8 infections among poultry workers in the two provinces with H3N8 cases.

Findings

The clinical symptoms of the patient were mild, including fever, sore throat, chills, and a runny nose. The patient's fever subsided on the same day of hospitalisation, and these symptoms disappeared 7 days later, presenting mild influenza symptoms, with no pneumonia. An H3N8 virus was isolated from the patient's throat swab specimen. The novel H3N8 virus causing human infection was first detected in a chicken farm in Guangdong Province in December, 2021, and subsequently emerged in several provinces.

Sequence analyses revealed the novel H3N8 AIVs originated from multiple reassortment events. The haemagglutinin gene could have originated from H3Ny AIVs of duck origin. The neuraminidase gene belongs to North American lineage, and might have originated in Alaska (USA) and been transferred by migratory birds along the east Asian flyway. The six internal genes had originated from G57 genotype H9N2 AIVs that were endemic in chicken flocks. Reassortment events might have occurred in domestic ducks or chickens in the Pearl River Delta area in southern China. The novel H3N8 viruses possess the ability to bind to both avian-type and human-type sialic acid receptors, which pose a threat to human health. No poultry worker in our study was positive for antibodies against the H3N8 virus.

Interpretation

The novel H3N8 virus that caused human infection had originated from chickens, a typical spillover. The virus is a triple reassortment strain with the Eurasian avian H3 gene, North American avian N8 gene, and dynamic internal genes of the H9N2 viruses. The virus already possesses binding ability to human-type receptors, though the risk of the H3N8 virus infection in humans was low, and the cases are rare and sporadic at present. Considering the pandemic potential, comprehensive surveillance of the H3N8 virus in poultry flocks and the environment is imperative, and poultry-to-human transmission should be closely monitored.

H3N8 is far from being the only novel flu virus with pandemic potential (see CDC IRAT List) - and while it would probably not produce as severe of a pandemic as H5 or H7 avian flu - it does tick a lot of the boxes.

As we've discussed often (see Are Influenza Pandemic Viruses Members Of An Exclusive Club?) - the progression of human influenza pandemics over the past 130 years appears to have been H2, H3, H1, H2, H3, H1, H1 . . . .

Credit ECDC – 125 years of Pandemic History

For whatever reasons, H1, H2, and H3 viruses appear to be more likely to spark human pandemics than other subtypes, which make the emergence of a new, apparently `fit', H3 virus worthy of our attention.In 1968, another H3 virus emerged out of China, sparking the 3rd influenza pandemic of the 20th century, and its descendants (H3N2) continue to spread as seasonal flu 54 years later.

We'll have to wait to see if history repeats itself, but whether it is sparked by H3N8 - or some other emerging subtype - another flu pandemic is inevitable.

It's just a matter of time.