#17,301

Prior to 2016, carriage of HPAI H5N1 by most wild birds was limited (see PNAS: The Enigma Of Disappearing HPAI H5 In North American Migratory Waterfowl), but as HPAI H5 continues to evolve and spread around the world we've seen major changes in the types of wild birds it now infects.

Last summer, in DEFRA: The Unprecedented `Order Shift' In Wild Bird H5N1 Positives In Europe & The UK, we saw the dramatic shift (see graphic above) from migratory water birds to native, sedentary wild bird species, including seabird populations.

(Translated)

Alert to bird flu in black-headed gulls

February 20, 2023

At the moment - mid-February 2023 - there are signs that highly pathogenic avian flu is leading to increased mortality among black-headed gulls in France, Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. We would like to call on everyone to be alert to this and to report any finds of sick or dead black-headed gulls. Vulnerable situations can arise, especially in sleeping areas and in breeding colonies, which become occupied from March onwards, because large numbers of birds stay here close together with many opportunities for virus transmission. Early warnings, informing local site managers and clearing carcasses can help limit mortality in these types of places.

Since the last week of January, the number of reports of sick and dead black-headed gulls received by DWHC and Sovon has increased. Highly pathogenic bird flu has now been confirmed in a total of five dead black-headed gulls in the vicinity of Rotterdam, Dordrecht, the Europoort and Leiden (all in South Holland) and near Ermelo (Gelderland). Entries from Flevoland, Limburg, North Brabant, North Holland, Overijssel and Utrecht are currently being examined.

Significant deaths in black-headed gulls were also observed elsewhere in Europe in early 2023, such as in France. [ https://www.francetvinfo.fr/sante/maladie/grippe-aviaire/grippe-aviaire-les-mouettes-sont-decimees-par-la-maladie_5640599.html .] Last breeding season, the species was also sensitive for the highly pathogenic H5N1 virus, but this rate of mortality was not established in the Netherlands at the time.

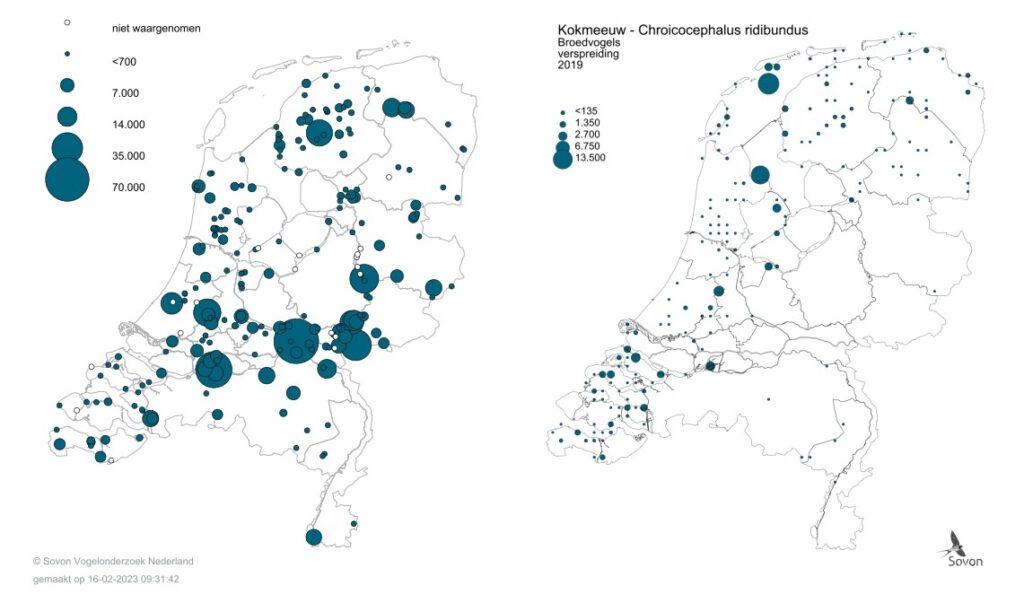

Sleeping places of black-headed gulls are often in open water and breeding colonies are often in hard-to-reach places, such as on islands or in open swamps. There is currently no complete picture of the situation there.Location of gull roosts where black-headed gulls have been counted since 2000 (left) and breeding colonies of black-headed gulls in 2019 (right).

Carcasses of infected birds can be a source of contamination for their environment. There are indications that disposing of these carcasses helps to mitigate the effects of avian flu outbreaks, for example from experiences during the mass deaths in sandwich tern colonies in the Netherlands, Dalmatian pelicans in Greece and black-footed penguins in Namibia. However, more research is needed to indicate to what extent and in which species these efforts help reduce exposure of healthy wildlife to highly pathogenic avian influenza.First-year (front) and adult Black-headed Gulls (behind) can still be distinguished from each other at the moment. If a dead Black-headed Gull is found, also state its age, so that we gain more insight into the impact of bird flu on the population. (Photo: Roy Slaterus)

However, knowing what is going on is a requirement to be able to take action at all. If you have observed sick or dead birds, please report this, even if it concerns other species than black-headed gulls. You can report via the websites of the DWHC or Sovon . For more information about cleaning up dead birds, please refer to https://dwhc.nl/vragen/#opruimen .

As avian flu continues to expand its host range, it is likely to find additional opportunities to evolve and adapt, potentially in unexpected and unwelcome directions.

While we understandably worry most about spillovers into mammals (see WOAH: Statement on Avian Influenza and Mammals), what happens in other avian species may provide a pathway for equally unexpected developments.