As the chart above illustrates - prior to 2019 - avian epizootics were rare, and sporadic events in Europe. Over the past 3 years, however, the virus has become endemic, persisting (albeit at lower levels) throughout the summer.

The HPAI H5 threat has changed substantially over the past 7 years, starting out with H5N8 in 2016, then transitioning (via reassortment) to H5N6 in 2018, and then finally to H5N1 in 2020. And with these changes in subtype came changes in its behavior.

While H5N1 is the dominant subtype, there dozens of genotypes circulating in Europe, with even more globally. Some of these genotypes are likely more dangerous, or better adapted to mammals, than others.

Over time, the virus has also expanded its host range, both in mammals and wild bird species (see chart below), moving from primarily affecting waterfowl (in blue) to heavily impacting shorebirds (in green).

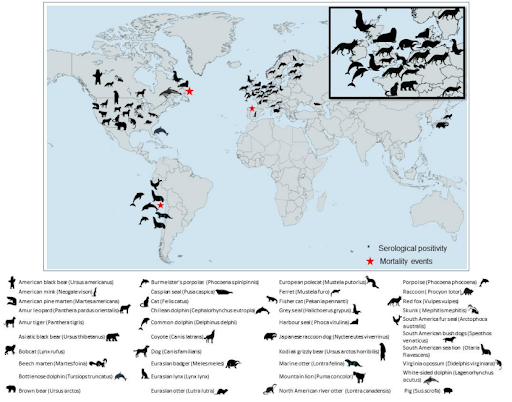

Even more concerning, we've seen a record number of mammalian spillover events around the world, causing - in several cases - mass mortality events. Surveillance and reporting from many regions of the world being limited, these likely represent only a fraction of the actual number of spillover events.

While none of this tells us whether H5N1 has what it takes to spark a human pandemic, it does tell us that the virus continues to evolve, and with greater diversity and increased geographic range come more opportunities to adapt to humans.

This latest ECDC/EFSA overview runs 45 pages, so I'll just post the abstract and a couple of excerpts, and invite you to follow the link to download the full document.

Avian influenza overview March – April 2023

European Food Safety Authority, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, European Union Reference Laboratory for Avian Influenza, Cornelia Adlhoch, Alice Fusaro, José L Gonzales, Thijs Kuiken, Grazina Mirinaviciute, Éric Niqueux, Karl Stahl, Christoph Staubach, Calogero Terregino, Alessandro Broglia, Lisa Kohnle and Francesca Baldinelli

Between 2 March and 28 April 2023, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5Nx) virus, clade 2.3.4.4b, outbreaks were reported in domestic (106) and wild (610) birds across 24 countries in Europe. Poultry outbreaks occurred less frequently compared to the previous reporting period and compared to spring 2022. Most of these outbreaks were classified as primary outbreaks without secondary spread and some of them associated with atypical disease presentation, in particular low mortality.

In wild birds, black-headed gulls continued to be heavily affected, while also other threatened wild bird species, such as the peregrine falcon, showed increased mortality. The ongoing epidemic in black-headed gulls, many of which breed inland, may increase the risk for poultry, especially in July August, when first-year birds disperse from the breeding colonies.

HPAI A(H5N1) virus also continued to expand in the Americas, including in mammalian species, and is expected to reach the Antarctic in the near future. HPAI virus infections were detected in six mammal species, particularly in marine mammals and mustelids, for the first time, while the viruses currently circulating in Europe retain a preferential binding for avian-like receptors.

Since 13 March 2022 and as of 10 May 2023, two A(H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b virus detections in humans were reported from China (1), and Chile (1), as well as three A(H9N2) and one A(H3N8) human infections in China. The risk of infection with currently circulating avian H5 influenza viruses of clade 2.3.4.4b in Europe remains low for the general population in the EU/EEA, and low to moderate for occupationally or otherwise exposed people.

(SNIP)

2.6 ECDC risk assessment

The risk assessment remains valid and unchanged:

Overall, the risk of infection with avian influenza viruses of the currently circulating clade 2.3.4.4b in Europe for the general public in EU/EEA countries is considered to be low. The risk to occupationally or otherwise exposed groups to avian influenza infected birds or mammals has been assessed as low to moderate.

The viral genotype does not predict the viral phenotype and therefore a high uncertainty is associated with any assessment of the risk for humans, particularly due to the high variability and diversification of the avian influenza viruses of clade 2.3.4.4b with many reassorted subtypes and genetic lineages co-circulating in Europe and globally as well as the sporadic occurrence of various mutations that could increase the transmission to and replication in humans. Reassortment events will likely continue globally leading to a more complex situation.

While H5N1 is current at the top of our hit parade, it isn't the only pandemic threat out there.

The CDC actively follows 23 subtypes of Zoonotic Influenza on their IRAT List, and as we discussed yesterday in China: Emergence of a Novel Reassortant H3N6 Canine Influenza Virus, new subtypes with pandemic potential continue to emerge.

Today's report also addresses recent human infections by H3N8, H5N6, and H9N2 as well.