#17,184

We're we not already in the third year of a deadly COVID pandemic, and simultaneously battling an array of re-emerging respiratory viruses (RSV, Influenza, Strep A, etc.), the biggest infectious disease story would undoubtedly be the unprecedented spread, and persistence, of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses in wild birds around the globe.

Prior to the 2016/17 avian H5N8 epizootic, the impact of HPAI H5 in Europe had been relatively small, usually involving anywhere from a handful to a few dozen widely scattered outbreaks in poultry each year.

But as the above chart illustrates, Europe saw a record setting epizootic in 2016-2017, after the clade 2.3.4.4b H5Nx virus reassorted - probably in China or Russia - and became more pathogenic in some avian species, while increasing its carriage in others.

Three relatively quiet years, and several mutations later, the virus returned in 2020, producing another record epizootic. It remained at very low levels over the summer of 2021, only to return even stronger in the fall.

Meanwhile, HPAI H5 has greatly expanded its geographic range, has shown a worrisome ability to infect - and kill - mammalian wildlife, and has racked up an impressive number of `1sts' over the past year, including:Since then - while it did decrease somewhat over the summer of 2022 - it has never really gone away, sparking concerns that it has (or will) become endemic in European birds.

The 2022-2023 avian flu season in on track to become be even bigger still and while the virus hasn't (yet) proven to be a serious threat to human health, it continues to evolve in unpredictable ways. Over the past few months many countries and public health entities issued public health & surveillance guidance due to human health concerns over HPAI's spread.

- The first human infections (In the U.S., England & Spain)

- Its designation last May as a zoonotic virus by the CDC and the ECDC

- Its crossing of both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans to North America via migratory birds

- The very first detection of HPAI H5 in South America (Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela & Chile).

- Its first detection in the Arctic (see HPAI Detected In Arctic (Svalbard) For the First Time)

- Infections reported in foxes, porpoises, and bears (among other mammals), often with severe neurological manifestations.

- Its unusual persistence over the summer months (see Ain't No Cure For the Summer Bird Flu)

- Its Unprecedented `Order Shift' In Wild Bird H5N1 Positives In Europe & The UK

This week the ECDC/EFSA has published their latest quarterly overview of the avian flu situation in Europe, and around the world. Among their findings, 8 new genotypes have appeared in Europe over the past 3 months (note: we've seen similar rapid evolution in North America as well).

Avian influenza overview September – December 2022

Monitoring

20 Dec 2022

Publication series: Avian influenza overview

Time period covered: September 2022 – December 2022.

This scientific report provides an overview of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus detections in poultry, captive and wild birds as well as noteworthy outbreaks of low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) virus in poultry and captive birds, and human cases due to avian influenza virus that occurred in and outside Europe between 10 September and 2 December 2022.

Executive summary

Between October 2021 and September 2022 Europe has suffered the most devastating highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) epidemic with a total of 2,520 outbreaks in poultry, 227 outbreaks in captive birds, and 3,867 HPAI virus detections in wild birds. The unprecedent geographical extent (37 European countries affected) resulted in 50 million birds culled in affected establishments. In the current reporting period, between 10 September and 2 December 2022, 1,163 HPAI virus detections were reported in 27 European countries in poultry (398), captive (151) and wild birds (613). A decrease in HPAI virus detections in colony-breeding seabirds species and an increase in the number of detections in waterfowl has been observed.

The continuous circulation of the virus in the wild reservoir has led to the frequent introduction of the virus into poultry populations. It is suspected that waterfowl might be more involved than seabirds in the incursion of HPAI virus into poultry establishments. In the coming months, the increasing infection pressure on poultry establishments might increase the risk of incursions in poultry, with potential further spread, primarily in areas with high poultry densities.

The viruses detected since September 2022 (clade 2.3.4.4b) belong to eleven genotypes, three of which have circulated in Europe during the summer months, while eight represent new genotypes. HPAI viruses were also detected in wild and farmed mammal species in Europe and North America, showing genetic markers of adaptation to replication in mammals. Since the last report, two A(H5N1) detections in humans in Spain, one A(H5N1), one A(H5N6) and one A(H9N2) human infection in China as well as one A(H5) infection without NA-type result in Vietnam were reported, respectively. The risk of infection is assessed as low for the general population in the EU/EEA, and low to medium for occupationally exposed people.

- EN - [PDF-3.09 MB]

While this report is focused on Europe, many other parts of the world - including North America and Asia - are reporting record outbreaks of avian flu as well. The latest from the USDA finds more than 15 million captive birds have been killed in the past 3 months.

Much like in Europe, avian flu never completely vanished over the summer in the United States and Canada, raising concerns that it is becoming endemic here as well.

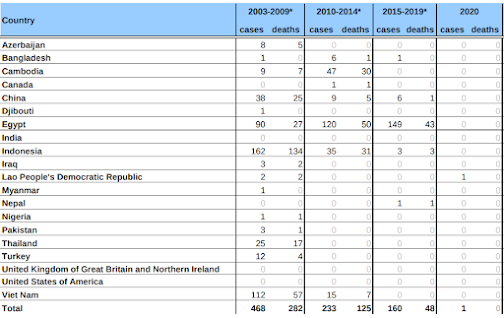

While this particular clade (2.3.4.4b) of HPAI has - to our knowledge - never seriously sickened a human, other closely related clades of H5N1 and H5N6 have, resulting in hundreds of infections and deaths, primarily in Asia and the Middle East (see WHO chart below).

Note: This chart doesn't include the 80+ cases of H5N6 reported by China, the 1500+ cases of H7N9, or any of the other occasional spillovers of avian flu (H9N2, H3N8, H10N8, etc.) that often go unreported.

While the future evolution of these avian viruses is unknowable - and there may even be a `species barrier' that prevents an H5 virus from sparking a human pandemic (see Are Influenza Pandemic Viruses Members Of An Exclusive Club?) - public health agencies like the CDC, ECDC, and WHO are taking the threat seriously.

If not H5N1, something else will surely come along, probably sooner rather than later.

Which is why we need to be getting ready for the next pandemic now, while there is still time to make meaningful preparations.