#17,343

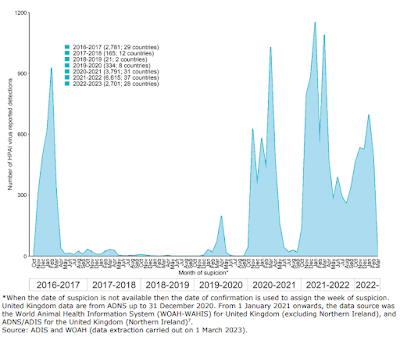

In 2016, Europe saw its first major HPAI H5 (clade 2.3.4.4b) epizootic (see chart above). Prior to that, there had been scattered bird flu outbreaks going back a dozen years, that only rarely exceeded a few dozen cases each winter.

Following the 2016 outbreak, there was nearly a 3-year lull (2017-2020).

After a brief blip in the spring of 2020, avian flu went quiet again over the summer, only to return in the fall with a record-setting epizootic - even bigger than 2016 - that never quite went away the following summer.

The HPAI H5 virus had changed over these five years, starting out as H5N8 in 2016, then transitioning (via reassortment) to H5N6 in 2018, and then finally to H5N1 in 2020. And with these changes in subtype came changes in its behavior.

The new virus was more easily carried by some migratory birds, increasing its ability to travel long distances, and it found its way into resident birds as well, enabling its persistence over the summer. Equally concerning the virus was beginning to spill over into mammals (see Netherlands: Two Foxes Test Positive For (non-Zoonotic) Avian H5N1).

H5N1 returned with a vengeance in the fall of 2021, and it is remained a constant threat since them - not only in Europe and Asia - but making its way to both North and South America. Adding to the concern, we've now seen rare, but occasionally severe, human infections.

Today the ECDC/EFSA has published their latest quarterly overview of the avian flu situation in Europe, and around the world. First the link and the summary for the 43-page document, after which we'll look at a couple of excerpts.Avian influenza overview December 2022 – March 2023

Surveillance report

13 Mar 2023

Between 3 December 2022 and 1 March 2023 highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) virus, clade 2.3.4.4b, was reported in Europe in domestic (522) and wild (1,138) birds over 24 countries. An unexpected number of HPAI virus detections in sea birds were observed, mainly in gull species and particularly in black-headed gulls (large mortality events were observed in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Italy). The close genetic relationship among viruses collected from black-headed gulls suggests a southward spread of the virus.Moreover, the genetic analyses indicate that the virus persisted in Europe in residential wild birds during and after the summer months. Although the virus retained a preferential binding for avian-like receptors, several mutations associated to increased zoonotic potential were detected.

The risk of HPAI virus infection for poultry due to the virus circulating in black-headed gulls and other gull species might increase during the coming months, as breeding bird colonies move inland with possible overlap with poultry production areas.Worldwide, HPAI A(H5N1) virus continued to spread southward in the Americas, from Mexico to southern Chile. The Peruvian pelican was the most frequently reported infected species with thousands of deaths being reported. The reporting of HPAI A(H5N1) in mammals also continued probably linked to feeding on infected wild birds.In Peru, a mass mortality event of sea lions was observed in January and February 2022. Since October 2022, six A(H5N1) detections in humans were reported from Cambodia (a family cluster with 2 people, clade 2.3.2.1c), China (2, clade 2.3.4.4b), Ecuador (1, clade 2.3.4.4b), and Vietnam (1, clade 2.3.4.4b), as well as two A(H5N6) human infections from China.The risk of infection with currently circulating avian H5 influenza viruses of clade 2.3.4.4b in Europe is assessed as low for the general population in the EU/EEA, and low to moderate for occupationally or otherwise exposed people.

Download

Avian influenza overview December 2022 – March 2023 - EN - [PDF-2.49 MB]

There is always a lot to unpack in these technical briefings, but one of the things we are watching closely is the continued evolution of the H5Nx virus as it treks around the globe. In their last assessment (Sept-Dec 2022) the ECDC/EFSA reported:

The viruses detected since September 2022 (clade 2.3.4.4b) belong to eleven genotypes, three of which have circulated in Europe during the summer months, while eight represent new genotypes.

Their latest analysis finds the expansion in genotypes, and its spread to new species, has continued.

Since October 2020, 6 subtypes (A(H5N1), A(H5N2), A(H5N3), A(H5N4), A(H5N5), A(H5N8)) and more than 60 different genotypes have been identified in Europe. While the 2020-2021 epidemiological year was dominated by the H5N8-A/Duck/Chelyabinsk/1207- 1/2020-like genotype, the 2021–2022 epidemiological year was mainly driven by three H5N1 genotypes, H5N1-A/Eurasian_Wigeon/Netherlands/1/2020-like, H5N1- A/duck/Saratov/29-02/2021-like and H5N1-A/Herring_gull/France/22P015977/2022-like.

Differently from the previous epidemics in Europe and based on the available genetic data, no new virus incursions seem to have occurred in Europe during the 2022-2023 epidemiological year.

Since October 2022, 16 distinct genotypes have been identified among the characterized viruses. Four of them have been circulating from the 2021-2022 epidemiological year, while the remaining 12 genotypes have newly emerged very likely from reassortment events with AIVs circulating in Eurasian wild bird populations. The majority of the characterized viruses belong to genotype H5N1-A/duck/Saratov/29- 02/2021-like, which has been the most prevalent since the beginning of 2022. However, starting from December 2022, a rapid increase in the number of detections of the H5N1 A/Herring_gull/France/22P015977/2022-like genotype has been recorded.

We are also closely following the continued spill over of HPAI H5 into mammals. The following describes only cases reported within the EU/EEA.

Genetic diversity of A(H5N1) viruses in mammals

Since October 2020, complete genome sequences of 57 HPAI A(H5) viruses of clade 2.3.4.4b collected from 12 distinct mammalian species (badger, cat, coati, ferret, fox, lynx, mink, otter, polecat, porpoise and seal) in 13 European countries were generated.

The characterized viruses belong to 8 different A(H5N1) and A(H5N8) genotypes previously identified in birds, with most of the viruses (75%) belonging to the two most widespread genotypes in birds in Europe (H5N1 A/Eurasian_Wigeon/Netherlands/1/2020-like, H5N1 A/duck/Saratov/29-02/2021-like).

Mutations identified in A(H5N1) viruses from mammals

About half of the characterized viruses contain at least one of the adaptive markers associated with an increased virulence and replication in mammals in the PB2 protein (E627K, D701N or T271A) (Suttie et al., 2019). These mutations have never (T271A) or rarely (E627K, D701N) been identified in the HPAI A(H5) viruses of clade 2.3.4.4b collected in birds in Europe since October 2020 (<0.5% of viral sequences from birds).

This observation suggests that these mutations with potential public health implications have likely emerged upon transmission to mammals. Moreover, the viruses collected in October 2022 from a HPAI A(H5N1) outbreak in intensively farmed minks in northwest Spain (Aguero et al., 2023) shows mutations in the NA protein which cause disruption of the second sialic acid binding site (2SBS). This feature is typical of human-adapted influenza A viruses, which may favour the emergence of mutations in the receptor binding site of the HA protein (de Vries and de Haan, 2023). These same mutations were detected also in seven A(H5N1) viruses from birds.

Although the ECDC's current assessment puts the risks of HPAI infection for the general public as being LOW, they do provide some caveats in the fine print.

(Excerpt)

While the future evolution of these avian viruses is unknowable, there are an awful lot of viral pieces in motion, and most of their activity occurs in places where we have little or no visibility.However, the expansion of mammal species identified infected with A(H5N1) viruses as well as the detection of viruses carrying markers for mammalian adaptation in other genes such as the PB2 that correlated with increased replication and virulence in mammals, is of concern.

The additional reports of transmission events to and potentially between mammals, e.g. mink, sea lion, seals, foxes and other carnivores as well as seroepidemiological evidence of transmission to wild boar and domestic pigs, associated with evolutionary processes including mammalian adaptation are of concern and need to be closely followed up.

With the wide geographical distribution of avian influenza viruses and high number of detections also in wild birds and mammals, sporadic human cases infected with HPAI viruses cannot be ruled out whenever people are exposed to infected sick or dead birds. The likelihood of travel-related importation of human avian influenza cases from countries where the viruses are detected in poultry or wild birds is considered to be very low.

The uncertainty of this risk assessment is high due to the high variability and diversification of the avian influenza viruses of clade 2.3.4.4 with many reassorted subtypes and genetic lineages co-circulating in Europe and globally. Reassortment events will continue and zoonotic transmission of avian influenza viruses cannot be fully excluded in general when avian influenza viruses are present in birds.