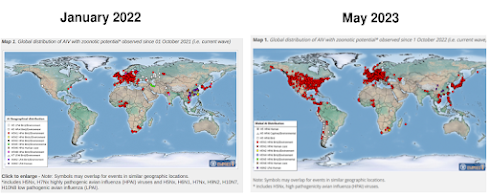

North and South America are now heavily impacted, joining both Europe and East Asia.

Remarkably, even though H5N1 emerged in Southeast Asia more than 25 years ago, and has been widely reported across much of the Indonesian archipelago for decades, the virus has never managed to get a foothold in Oceania.The only large land masses not reporting avian flu are Australia, New Zealand, New Guinea (aka `Oceania') and Antarctica.

These stark faunal differences also extend to birds, reptiles, and even insects.

Importantly for avian flu, very few migratory birds appear to cross the Wallace line (see The Australo-Papuan bird migration system: another consequence of Wallace's Line).

That said, there were brief reports in 2007 of H5N1 being detected in poultry in both West Papua and the Maluku Islands; both of which lie on the Eastern side of the Wallace line. Details (and sequences) are limited, since the Indonesian government was notoriously refusing to share bird flu information at the time.

The recent move of H5N1 into previously unaffected avian species, however, may provide new opportunities for the virus to make it into Australia and surrounding areas. This was a concern addressed 15 years ago in the following paper published in Ecology & Society.

Australia is separated from the Asian faunal realm by Wallace’s Line, across which there is relatively little avian migration. Although this does diminish the risk of high pathogenicity avian influenza of Asian origin arriving with migratory birds, the barrier is not complete. Migratory shorebirds, as well as a few landbirds, move through the region on annual migrations to and from Southeast Asia and destinations further north, although the frequency of infection of avian influenza in these groups is low.

Nonetheless, high pathogenicity H5N1 has recently been recorded on the island of New Guinea in West Papua in domestic poultry. This event increases interest in the movements of birds between Wallacea in eastern Indonesia, New Guinea, and Australia, particularly by waterbirds. There are frequent but irregular movements of ducks, geese, and other waterbirds across Torres Strait between New Guinea and Australia, including movements to regions in which H5N1 has occurred in the recent past. Although the likelihood of avian influenza entering Australia via an avian vector is presumed to be low, the nature and extent of bird movements in this region is poorly known.

So far, Oceania's luck continues to hold, but as the following update from Wildlife Health Australia explains, the risks of seeing H5N1 are higher today than ever before. I've only posted the link and an excerpt from the 13-page PDF report, so follow the link to read it in its entirety.

Key points

• Outbreaks of high pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) have occurred in both poultry and wild birds in Asia, Europe, Africa and North and South America.

• From 2021, the frequency and geographic range of overseas outbreaks has increased.

• These pathogenic strains of avian influenza virus have not been detected in Australia.

• The risk of HPAI strains being introduced into Australia from overseas has previously been considered low.

• The return of migratory birds from the northern hemisphere to Australia during spring (September to November) represents a period during which there is an increased chance of introduction of HPAI viruses into Australia. The current global situation means there is likely a higher chance for an introduction of HPAI viruses into Australia during this period, compared to previous years.

Introductory statement

Avian influenza (AI) is an infectious disease of birds caused by influenza virus type A strains. Avian influenza viruses (AIVs) are found worldwide in numerous bird species. Species in the avian orders Anseriformes (waterfowl) and Charadriiformes(shorebirds and gulls) are the main natural reservoirs for these viruses.

Outbreaks of high pathogenicity AI (HPAI) H5 have occurred in Asia since 2003, in both poultry and wild birds, spreading to Europe, Africa and North America. Since 2021, the frequency and geographic range of outbreaks occurring overseas has increased, and outbreaks have been recorded for the first time in wild birds and poultry in North and South America. These pathogenic strains have not been detected in Australia [1] .

Low pathogenicity AIVs have been detected in wild birds in Australia, however mortality due to AIVs have not been reported in feral or native free-ranging birds [2] .

The role of wild birds in the epidemiology of AIV has been investigated in detail over recent decades, with extensive global surveillance programs targeting the main avian reservoir hosts. Previous research and risk analyses have determined the risk of HPAI strains being introduced to Australia via migratory birds to be low [3-6] . However, with increased frequency and geographic range of overseas outbreaks, there is likely a higher chance for an introduction of HPAI viruses into Australia compared to previous years. The period of concern is when migratory birds return from the northern hemisphere to Australia during spring (September to November)