#17,502

Influenza A viruses - which are believed native to aquatic waterfowl - are categorized by the two proteins they carry on their surface; their HA (hemagglutinin) and NA (neuraminidase), producing subtypes like H1N1, H3N2, or H5N1.

These numbers can, and do, change. When I began blogging about flu 18 years ago there were only 15 recognized HA subtypes, and 9 NA. In 2005, however, a 16th HA subtype was characterized by Fouchier and Osterhaus after its detection in black-headed gulls in Sweden.

A little over a decade ago, the discovery of a 17th HA was announced (see A New Flu Comes Up To Bat) - albeit quite unusually, this detection was in a South American bat species - not in a bird. Its neuraminidase (NA), and internal genes, were also highly divergent from previously known influenzas.

Two years later (2013) another new subtype (H18N11) was identified, again in South American Bats (see PLoS Pathogens: New World Bats Harbor Diverse Flu Strains), leading to speculation that these mammalian-adapted flu viruses might someday jump to other species.While H17 and H18 influenza A viruses have never been detected outside of bats, in recent years we've seen avian-origin influenza subtypes showing up in bats (see Preprint: The Bat-borne Influenza A Virus H9N2 Exhibits a Set of Unexpected Pre-pandemic Features).

Genetic characterization of a new candidate hemagglutinin subtype of influenza A viruses

Sasan Fereidouni, Elke Starick, Kobey Karamendin, Cecilia Di Genova, Simon D. Scott,

Yelizaveta Khan, show all

Abstract

Avian influenza viruses (AIV) have been classified on the basis of 16 subtypes of hemagglutinin (HA) and 9 subtypes of neuraminidase. Here we describe genomic evidence for a new candidate HA subtype, nominally H19, with a large genetic distance to all previously described AIV subtypes, derived from a cloacal swab sample of a Common Pochard (Aythya ferina) in Kazakhstan, in 2008.

Avian influenza monitoring in wild birds especially in migratory hotspots such as central Asia is an important approach to gain information about the circulation of known and novel influenza viruses. Genetically, the novel HA coding sequence exhibits only 68.2% nucleotide and 68.5% amino acid identity with its nearest relation in the H9 (N2) subtype. The new HA sequence should be considered in current genomic diagnostic AI assays to facilitate its detection and eventual isolation enabling further study and antigenic classification.

Introduction

Metapopulations of wild aquatic birds (waterfowl and shorebirds) represent the primary natural reservoir of avian influenza A viruses (AIVs) of which 16 hemagglutinin (HA) and nine neuraminidase (NA) subtypes are currently known. Two further subtypes, H17 and H18, were recently discovered in Little yellow-shouldered (Sturnia lilium) and a flat-faced fruit bats (Artibeus planirostris) respectively, but not in any avian species or human to date [1-2]. The most recent IAV subtype identified in an avian species was the H16 subtype which was isolated from a Black-headed gull in 2005 [3]. An important part of our knowledge regarding low pathogenicity avian influenza viruses (LPAIVs) has been acquired via wildlife monitoring studies. Such wild bird studies have been carried out over the past few decades, especially after emergence and geographical expansion of high pathogenicity AIVs (HPAIVs) of the H5Nx subtype since 2005. Yet, no evidence for another new AIV subtype has been reported since, until now [4-12].

We have examined approximately 8000 oropharyngeal and cloacal samples in the framework of an AIV monitoring program in wild birds in Kazakhstan from 2006 to 2011. Molecular screening of samples and subsequent sequencing of AIV positive samples revealed a number of known AIV subtypes but a single influenza A virus HA sequence could not be classified within the existing subtypes. Here we describe sequence analyses of this sample providing genomic evidence for a novel HA subtype of AIV from a Common Pochard (Aythya ferina). With more than 30% genetic distance [3,13], based on the HA coding region nucleotide sequence, to its closest relatives in the H9 subtype, the novel sequence represents a potential candidate new subtype, nominally H19.

(SNIP)

The HA of this virus is genetically significantly divergent from all known AIVs, and appears to represent a separate monophyletic group established as a sister clade to the H9 phylogenetic branch. The H9 HA sequence obtained from bats in Egypt is likewise close to the root of H9, although it is reported to represent a true H9 subtype with an identity of 73% to avian H9 viruses [22]. The full HA coding region of Kz52 showed only 68.2% sequence homology with closest related H9 subtypes viruses.

In addition, as the genetic distance on the basis of amino acid sequences from other known subtypes was more than 30%, in accordance with current AIV subtype classification [3,13], thus we suggest the Kz52 as a potential candidate for a new subtype, although antigenic classification is essential to confirm this, as described in WHO guidelines [24].

Nevertheless, this represents the first new avian HA sequence as substantially distinct from all other subtypes, as of the most recent additions, H16 AIV in 2005 [3], and two bat-origin influenza viruses identified a decade ago [H17, H18: 1-2].

(Continue . . . )

While this discovery is primarily of academic interest, this paper is reminder that there is still a lot we still don't know about the viral world around us. A decade ago, in mBio: A Strategy To Estimate The Number Of Undiscovered Viruses, we saw an estimate that there were at least 320,000 unidentified mammalian viruses awaiting discovery.

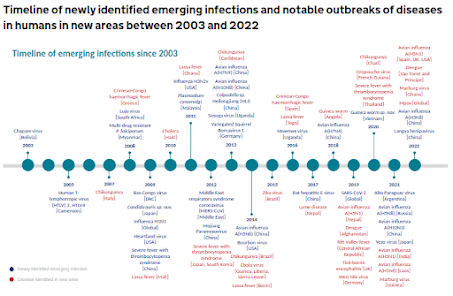

Every few months we learn about new or expanding threats in the wild (see UK HAIRS Timeline below), and if anything, this trend appears to be accelerating.Most are expected to be benign or of little consequence, but among them are probably scores of high consequence pathogens.