#17,520

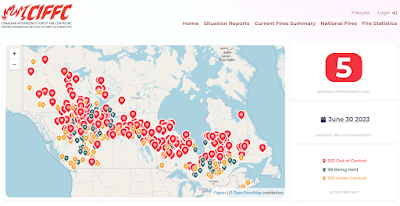

Canadian wildfires continue to rage after getting an early start this year, which saw the CIFFC's National Preparedness Level raised to its highest level (5) in the 2nd week of May, and the number, and intensity of fires has only increased since then.

We've seen studies (see here and here) suggesting poor air quality in China may be a factor driving the severity of their yearly flu seasons. Particularly, but not exclusively, the effects of fine particles less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter (PM2.5).Today, there are roughly 500 wildfires burning, with half `out of control', and the immense amount of smoke being generated poses potential health hazards, both in Canada and in the United States.

The Impact of PM2.5 on the Host Defense of Respiratory System

Liyao Yang, Cheng Li and Xiaoxiao Tang*

The harm of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) to public health is the focus of attention around the world. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2015 (GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators, 2016) ranked PM2.5 as the fifth leading risk factor for death, which caused 4.2 million deaths and 103.1 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) loss, representing 7.6% of total global deaths and 4.2% of global DALYs.

Epidemiological studies have confirmed that exposure to PM2.5 increases the incidence and mortality of respiratory infections. The host defense dysfunction caused by PM2.5 exposure may be the key to the susceptibility of respiratory system infection.

Yesterday the CDC released a HAN Advisory - for clinicians, public health officials, and the public - outlining the threats, and providing advice (excerpts below). I'll have brief postscript after the break.

Wildfire Smoke Exposure Poses Threat to At-Risk Populations

Distributed via the CDC Health Alert Network

June 30, 2023, 1:30 PM ET

CDCHAN-00495

Summary

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is reminding healthcare professionals seeing patients affected by wildfire smoke to be alert to the possible adverse effects of smoke exposure, particularly among individuals at higher risk of severe outcomes. The acute signs and symptoms of smoke exposure can include headache, eye and mucous membrane irritation, dyspnea (trouble breathing), cough, wheezing, chest pain, palpitations, and fatigue. Wildfire smoke exposure may exacerbate respiratory, metabolic, and cardiovascular chronic conditions like asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and congestive heart failure.

Background

Climate change is increasing the vulnerability of many forests to wildfires and is also projected to increase the frequency of wildfires in certain regions of the United States. Wildfires produce high volumes of smoke each year, leading to unhealthy air quality levels, sometimes hundreds of miles away from the fire. Wildfire smoke is a mix of gases and fine particles from burning trees, plants, buildings, and other material. Patients who are very near the fire source may have smoke inhalation injury, which is caused by thermal (superheated gases), chemical (e.g., particulate matter and other irritants), and toxic (e.g., carbon monoxide, cyanide) effects of the products of combustion.

Wildfire smoke can affect people even if they are not near the fire source, due to exposure to particles of PM2.5, which are inhalable air pollutants with aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 microns.

Individuals especially at risk after exposure to wildfire smoke include people with:Children, older adults, or those who are pregnant are also especially at risk for severe outcomes.

- asthma,

- COPD, or

- cardiovascular disease (e.g., ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure)

Medical management consists of carefully assessing signs and symptoms, providing supportive and symptomatic care for smoke exposure, and treating possible existing respiratory and cardiovascular illness. Increased emergency department visits for respiratory and cardiovascular conditions can occur during the days immediately following wildfire smoke exposure, with increases in associated morbidity and mortality.

Appropriate and prompt treatment is crucial to reduce morbidity from wildfire smoke exposure. Counseling patients on protective measures, including being aware of current and predicted air quality levels, staying indoors, using air filtration, and using properly fitted N95 respirators when outdoors is also important for mitigating adverse effects.

Recommendations for Clinicians

- For patients who are very near the fire source who may have burns and/or smoke inhalation injury, follow Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines and consult your regional burn center.

- Consider smoke exposure in patients who live in wildfire smoke-affected areas identified on AirNow presenting with any of the signs and symptoms noted above, paying particular attention to those at higher risk of developing complications. Treatment is supportive and based on clinical presentation.

- Monitor healthcare capacity closely and plan for a possible increase in patient visits due to asthma, COPD, and metabolic and cardiovascular disease exacerbations.

- Proactively counsel patients on strategies to avoid or reduce smoke exposure, especially among individuals with asthma, COPD, or cardiovascular disease, children, older adults, and those who are pregnant. These strategies include, during times of poor air quality:

- Staying indoors, including clospoor air qualitying windows and doors, and using HVAC systems effectively to minimize exposure to wildfire smoke.

- Preventing further indoor air pollution by not smoking or using candles, gas, or aerosol sprays; not frying or broiling meat; and not vacuuming.

- Staying aware of current and predicted local air quality conditions using AirNow or other tools.

- Using a portable air cleaner or creating a cleaner air room in the home.

- Going to a designated cleaner air shelter (such as a school gymnasium, buildings at public fairgrounds, or a civic auditorium) during times of poor air quality.

- Selecting and using an N95 respirator when it is not possible to avoid exposure to wildfire smoke.

- Advise patients at higher risk for severe outcomes to monitor their symptoms more closely and ensure that their medication prescriptions are up-to-date and available.

Recommendations for Public Health Authorities

Recommendations for the Public

- Identify public places that can be used as clean air shelters.

- Relay information about local air quality to the public so people can make decisions about how to protect their health. Include approaches to reach members of at-risk populations.

- Use activity guidance to support decisions to postpone, relocate, or cancel outdoor activities and events.

- Advise the public about staying safe while cleaning up ash.

- Assess for a possible healthcare utilization surge related to wildfire smoke exposure.

- For additional guidance and strategies, please refer to Wildfire Smoke: A Guide for Public Health Officials.

For More Information

- Stay indoors and keep smoke outside by following the strategies outlined above.

- Limit your time outdoors. If you must go outside when smoke is visible or can be smelled, reduce your smoke exposure by wearing an N95 or P100 respirator.

- Keep track of smoke near you using AirNow’s “Fire and Smoke Map” or the AirNow app or by listening to the Emergency Alert System (EAS) and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Weather Radio.

- Call your regional poison center if you have questions about wildfire smoke exposure (1-800-222-1222).

- If you have a medical condition like asthma, COPD, or metabolic and cardiovascular disease that puts you at risk for a severe outcome from wildfire smoke exposure, monitor your symptoms, seek medical care when needed, and ensure that your prescriptions are up-to-date and that you have an adequate supply on hand.

- CDC Wildfires

- CDC Community Respirators and Masks

- CDC Climate Effects on Health: Wildfires

- Wildfire Smoke and Your Patients’ Health (web-based training for clinicians)

- Cascio WE. Wildland fire smoke and human health. Sci Total Environ. 2018 May 15;624:586-595. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.086. Epub 2017 Dec 27. PMID: 29272827; PMCID: PMC6697173.

- Directory of Local Health Departments – NACCHO

- CDC Wildfire Smoke Guidance for Public Health Officials & Professionals

- CDC Data Tool for Planning: National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network (Wildfires)

While we are currently enjoying a summer lull in influenza and COVID infections, excessive PM2.5 exposures now could be reducing our defenses against whatever viral, bacterial, or fungal threat comes in the fall.

All of which makes taking reasonable steps to protect your lungs against heavy wildfire smoke well worth considering.