#17,938

Last week, in Denmark SSI: Marked Increase In Parrot Fever Cases Over the Past 60 Days, we looked at reports of an unusual number of Psittacosis cases being reported by Denmark's SSI, along with similar media reports from Sweden.

Psittacosis - often called parrot fever - is a rarely reported, atypical bacterial pneumonia caused by Chlamydia psittaci, which is often carried by wild or captive birds.

Most infections are mild, and usually respond to antibiotic treatment, although untreated it can progress to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. While likely under-reported, the U.S. reports roughly 10 cases per year.

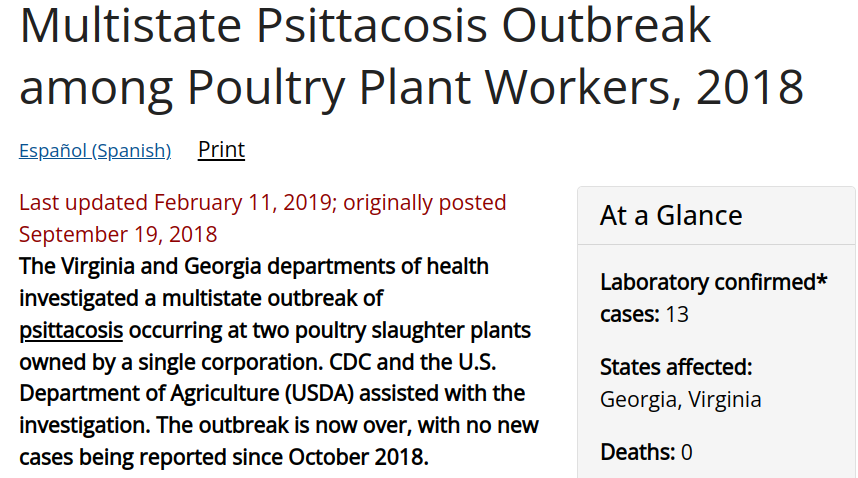

Psittacosis (aka `Parrot Fever') has occasionally sparked small outbreaks around the wolrd, such as the following CDC report on an outbreak at two U.S. poultry plants in 2018.

In 1929, before the advent of modern antibiotics, the United States experienced a short-lived `Parrot Fever Epidemic', spread by infected birds sold by a pet store in Maryland. By the time it was over, at least 169 cases were reported across several states, along with 33 deaths.

While normally spread by (direct or indirect) bird-to-human transmission, in recent years we've seen a few documented instances strongly suggesting human-to-human transmission.

- In 2012, the journal Eurosurveillance carried a report called Psittacosis outbreak in Tayside, Scotland, December 2011 to February 2012, involving four family members and a health-care worker, which suggested human-to-human transmission.

- The following year, in Sweden Reports Rare Outbreak Of Parrot Fever, we saw a credible report of human transmission of parrot fever, where a 75 year old man who died in Kronoberg appeared to have spread the infection to at least 8 close contacts, including healthcare personnel.

- In 2014, the ECDC's Eurosurveillance Journal carried a follow up report expanding the Swedish outbreak to 10 secondary cases.

- And in 2018 we saw another example, in PLoS Currents: A Psittacosis Outbreak Among Office Workers With Little Or No Bird Contact - UK.

Due to its length, I've only posted some excerpts. Follow the link to read the full report.

5 March 2024

Situation at a Glance

In February 2024, Austria, Denmark, Germany, Sweden and The Netherlands reported through the Early Warning and Response System (EWRS) of the European Union, an increase in psittacosis cases observed in 2023 and at the beginning of 2024, particularly marked since November-December 2023. Five deaths were also reported.

Exposure to wild and/or domestic birds was reported in most of the cases. Psittacosis is a respiratory infection caused by Chlamydophila psittaci (C. psittaci), a bacteria that often infects birds. Human infections occur mainly through contact with secretions from infected birds and are mostly associated with those who work with pet birds, poultry workers, veterinarians, pet bird owners, and gardeners in areas where C. psittaci is epizootic in the native bird population.

The concerned countries have implemented epidemiological investigations to identify potential exposures and clusters of cases. Additionally, implemented measures include the analysis of samples from wild birds submitted for avian influenza testing to verify the prevalence of C. psittaci among wild birds. The World Health Organization continues to monitor the situation and, based on the available information, assesses the risk posed by this event as low.

(SNIP)

Epidemiology

Chlamydophila psittaci is a bacterium that causes the zoonotic disease of psittacosis in humans. Human infections are generally associated with those who work with pet birds, poultry workers, veterinarians, pet bird owners, and gardeners in areas where C. psittaci is epizootic in the native bird population.

C. psittaci is associated with more than 450 avian species and has also been found in various mammalian species, including dogs, cats, horses, large and small ruminants, swine, and reptiles. However, birds, especially pet birds (psittacine birds, finches, canaries, and pigeons), are most frequently involved in causing human psittacosis. Disease transmission to humans occurs mainly through inhalation of airborne particles from respiratory secretions, dried faeces, or feather dust. Direct contact with birds is not required for infection to occur.

In general, psittacosis is a mild illness, with symptoms including fever and chills, headache, muscle aches and dry cough. Most people begin developing signs and symptoms within 5 to 14 days after exposure to the bacteria. Prompt antibiotic treatment is effective and allows avoiding complications such as pneumonia. With appropriate antibiotic treatment, psittacosis rarely (less than 1 in 100 cases) results in death.

WHO Risk Assessment

Overall, five countries in the WHO European region reported an unusual and unexpected increase in reports of cases of C. psittaci. Some of the reported cases developed pneumonia and resulted in hospitalization, and fatal cases were also reported.

Sweden has reported a general increase in psittacosis cases since 2017, which could be associated with the increased use of more sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panels. The increase in reported psittacosis cases across all countries requires additional investigation to determine whether it is a true increase in cases or an increase due to more sensitive surveillance or diagnostic techniques.

While birds that carry this disease could be crossing international borders, there is currently no indication of this disease being spread by humans nationally or internationally. Generally, people do not spread the bacteria that causes psittacosis to other people, so there is a low likelihood of further human-to-human transmission of the disease. If correctly diagnosed, this pathogen is treatable by antibiotics.

WHO continues to monitor the situation, and based on the available information, assesses the risk posed by this event as low.

WHO Advice

WHO recommends the following measures for the prevention and control of psittacosis:

- increasing the awareness of clinicians to test suspected cases of C. psittaci for diagnosis using RT-PCR.

- increasing awareness among caged or domestic bird owners, especially psittacines, that the pathogen can be carried without apparent illness.

- quarantining newly acquired birds. If any bird is sick, contact the veterinarian for an examination and treatment.

- conducting surveillance of C. psittaci in wild birds, potentially including existing specimens collected for other reasons.

- encouraging people with pet birds to keep cages clean, position cages so that droppings cannot spread among them and avoid over-crowded cages.

- promoting good hygiene, including frequent hand washing, when handling birds, their faeces, and their environments.

- standard infection-control practices and droplet transmission precautions should be implemented for hospitalized patients.