#18,002

While the risk of human infection is still believed to be quite low, the CDC is encouraging public health officials, and clinicians, to be alert to the possibility of H5N1 spilling over into humans (see CDC HAN #00506: HPAI A(H5N1) Virus: Identification of Human Infection and Recommendations for Investigations and Response).

As we've discussed previously, identifying cases of novel flu infection in the community isn't always possible. Every year a dozen or more novel swine variant infections are reported in the United States, but they are assumed to represent just the tip of the iceberg.

Since some individuals may only experience mild or moderate flu symptoms, many cases are likely never reported. During a small outbreak (n=13) of of H3N2v a dozen years ago, researchers estimated that fewer than 1 in every 200 cases was identified (see CID Journal: Estimates Of Human Infection From H3N2v (Jul 2011-Apr 2012).

We saw a similar estimate of the gap between actual and reported cases of H7N9 in China (see Lancet: Clinical Severity Of Human H7N9 Infection) during their first wave (2013), where researchers suggested the number of cases was likely between 12 and 200 times greater than reported.

In 2009, the pandemic H1N1 virus appears to have spilled over from swine in Mexico - and spread stealthily for several weeks - before it was publicly announced in late April (see ECDC Timeline).

A little over a year ago, in UK Novel Flu Surveillance: Quantifying TTD - UK health officials estimated the TTD (Time To Detect) a novel H5N1 virus in their community via passive surveillance could take weeks, and the virus might only be picked up after hundreds or possibly even thousands of infections.

(Excerpt)

The TTD is determined for a number of testing scenarios, estimating the point at which the outbreak will have grown large enough we expect to detect a case. This depends both on the growth rate and the severity (for hospital-based testing).

Testing scenarios modelled are:

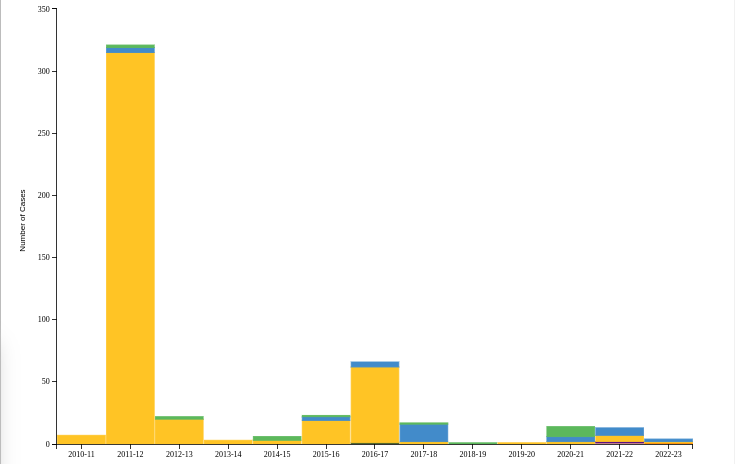

Figure 7 (above) shows the expected TTD in each scenario with an R of 1.2

- sampling of asymptomatic individuals in the community with coverage of 1 in 1,000 people tested daily

- sampling of asymptomatic individuals in the community with coverage of 1 in 200 people tested daily

- testing of all hospital admissions (with influenza-like illness (ILI) symptoms)

- testing of admissions to intensive care units (ICU) only (with ILI symptoms).

Under their best scenario (testing all hospital admissions with ILI symptoms), they estimate it could take nearly 3 weeks of community transmission before they might detect the first case. Worst case? More than 2 months.

Of course, it is possible to detect sporadic cases in specific risk groups (like dairy workers or poultry farmers) much sooner, assuming you are actively looking for them.

Whether you are dealing with humans, or livestock, or other potential hosts - the more you test - the better the chances of finding cases early.

None of this is to suggest there is currently community spread of HPAI H5N1. We've no evidence of that, and the virus still appears to need additional mutations before it can transmit efficiently in humans.

That said - even with the advanced surveillance systems we have in place in the U.S. or in the UK - we'd have to get very lucky to detect community transmission early in an outbreak.

With all of this in mind, the CDC has recently updated their Bird Flu Virus in Humans web page.

Bird Flu Virus Infections in Humans

Español | Other Languages Print

Information about the latest developments around avian influenza A(H5N1) is available at Bird Flu Current Situation Summary.

On This Page

Signs and Symptoms of Avian Influenza A Virus Infections in Humans

Detecting Bird Flu Avian Influenza A Virus Infection in Humans

Although avian (bird) influenza (flu) A viruses usually do not infect people, there have been some rare cases of human infection with these viruses. Illness in humans from avian influenza virus infections have ranged in severity from no symptoms or mild illness to severe disease that resulted in death. Avian influenza A(H7N9) virus and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) and A(H5N6) viruses have been responsible for most human illness from avian influenza viruses reported worldwide to date, including the most serious illnesses with high mortality.

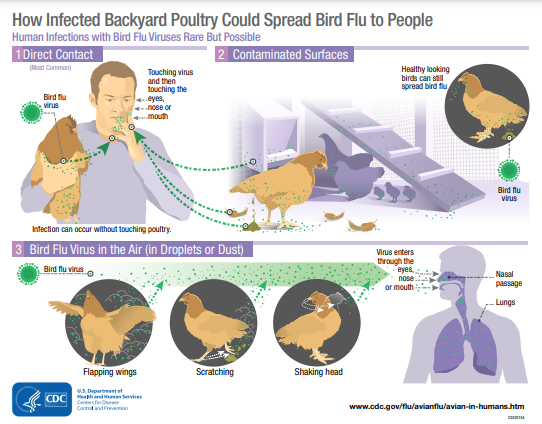

Infected birds shed avian influenza viruses through their saliva, mucous and feces. Other animals infected with avian influenza viruses may have virus present in respiratory secretions, different organs, blood, or in other body fluids, including animal milk. Human infections with avian influenza viruses can happen when virus gets into a person’s eyes, nose or mouth, or is inhaled. This can happen when virus is in the air (in droplets, small aerosol particles, or possibly dust) and deposits on the mucus membranes of the eyes or a person breathes it in, or possibly when a person touches something contaminated by viruses and then touches their mouth, eyes or nose.

Avian influenza viruses have been detected in many other species. Avoid contact with surfaces that appear to be contaminated with animal feces, raw milk, litter, or materials contaminated by birds or other animals with suspected or confirmed avian influenza virus infection. CDC has information about precautions to take with wild birds, poultry and other animals.

CDC has guidance for specific groups of people with exposure to poultry and other potentially infected animals, including poultry or dairy workers, for example, and people responding to bird flu outbreaks. Additional information is available at Information for People Exposed to Birds Infected with Avian Influenza Viruses of Public Health Concern.

In late March 2024, a human case of influenza A(H5N1) virus infection was identified after exposure to dairy cattle presumably infected with bird flu. Some bird flu infections of people have been identified in which the source of infection was unknown.

The spread of bird flu viruses from one infected person to a close contact is very rare, and when it has happened, it has only spread to a few people. However, because of the possibility that bird flu viruses could change and gain the ability to spread easily between people, monitoring for human infection and person-to-person spread is extremely important for public health.

Spread of Bird Flu Viruses Between Animals and PeoplePrevention and Antiviral Treatment of Bird Flu in PeopleExamples of Possible Human to Human TransmissionReported Human Infections with Bird Flu

Signs and Symptoms of Avian Influenza A Virus Infections in Humans

The reported signs and symptoms of bird flu virus infections in humans have ranged from no symptoms or mild illness [such as eye redness (conjunctivitis) or mild flu-like upper respiratory symptoms], to severe (such as pneumonia requiring hospitalization) and included fever (temperature of 100ºF [37.8ºC] or greater) or feeling feverish*, cough, sore throat, runny or stuff nose, muscle or body aches, headaches, fatigue, and shortness of breath or difficulty breathing. Less common signs and symptoms include diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, or seizures.

*Fever may not always be present

Detecting Bird Flu Avian Influenza A Virus Infection in Humans

Bird flu virus infection in people cannot be diagnosed by clinical signs and symptoms alone; laboratory testing is needed. Bird flu virus infection is usually diagnosed by collecting a swab from the upper respiratory tract (nose or throat) of the sick person. Testing is more accurate when the swab is collected during the first few days of illness.

For critically ill patients, collection and testing of lower respiratory tract specimens also may lead to diagnosis of bird flu virus infection. However, for some patients who are no longer very sick or who have fully recovered, it may be difficult to detect bird flu virus in a specimen.

CDC has posted guidance for clinicians and public health professionals in the United States on appropriate testing, specimen collection, and processing of samples from patients who might be infected with avian influenza A viruses.