#17,997

Seven years ago, I opened a blog writing:

A recurring theme in this blog has been the remarkable spread and growing diversity of (first) HPAI H5N1, followed later by a bevy of related H5Nx viruses (H5N2, H5N3, H5N5, H5N6, H5N8, etc.), all of which have diverged into a dizzying number of lineages, clades, subclades, and genotypes around the globe.

Of course, what seemed like a rapid spread and diversification of H5Nx viruses back then pales in comparison to what we've seen over the past 3 years.

Since 2021, HPAI H5Nx has literally exploded around the globe, infecting new (avian and mammalian) species, crossing both oceans and continents, and reinventing itself via reassortment at every opportunity.

As a segmented virus with 8 largely interchangeable parts, the flu virus is like a viral LEGO (TM) set which allows for the creation of unique variants called genotypes. The result being that we aren't facing a single HPAI H5N1 virus, but an array of (dozens) of similar H5 viruses, all on their own evolutionary path.

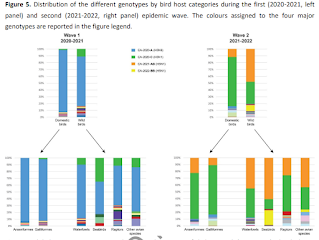

We've a report today on that viral diversity - at least in Europe, and during the 2020-2021 and 2021-2022 epidemic waves - that describes roughly 50 H5N1 genotypes in circulation over that time. When you add in variants generated in North & South America, and elsewhere, the number of unique H5N1 genotypes only increases.This is a lengthy (33 pages), and highly detailed report, so I've only reproduced the abstract below. Follow the link to read it in its entirety. I'll have a brief postscript after the break.

High pathogenic avian influenza A(H5) viruses of clade 2.3.4.4b in Europe – why trends of virus evolution are more difficult to predict

Alice Fusaro, Bianca Zecchin, Edoardo Giussani, Elisa Palumbo, Montserrat Agüero-García, Claudia Bachofen, Ádám Bálint, Fereshteh Banihashem, Ashley C Banyard, Nancy Beerens ... Show more

Virus Evolution, veae027, https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/veae027

Published:

06 April 2024 Article history

Abstract

Since 2016, A(H5Nx) high pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus of clade 2.3.4.4b has become one of the most serious global threats not only to wild and domestic birds, but also to public health. In recent years, important changes in the ecology, epidemiology and evolution of this virus have been reported, with an unprecedented global diffusion and variety of affected birds and mammalian species.After the two consecutive and devastating epidemic waves in Europe in 2020-2021 and 2021-2022, with the second one recognized as one of the largest epidemics recorded so far, this clade has begun to circulate endemically in European wild bird populations.This study used the complete genomes of 1,956 European HPAI A(H5Nx) viruses to investigate the virus evolution during this varying epidemiological outline. We investigated the spatiotemporal patterns of A(H5Nx) virus diffusion to/from and within Europe during the 2020-2021 and 2021-2022 epidemic waves, providing evidence of ongoing changes in transmission dynamics and disease epidemiology.We demonstrated the high genetic diversity of the circulating viruses, which have undergone frequent reassortment events, providing for the first time a complete overview and a proposed nomenclature of the multiple genotypes circulating in Europe in 2020-2022. We described the emergence of a new genotype with gull adapted genes, which offered the virus the opportunity to occupy new ecological niches, driving the disease endemicity in the European wild bird population.The high propensity of the virus for reassortment, its jumps to a progressively wider number of host species, including mammals, and the rapid acquisition of adaptive mutations make the trend of virus evolution and spread difficult to predict in this unfailing evolving scenario.

While there may be some comfort to be derived from the fact that so many genotypes have already been spawned without producing a `pandemic-capable' strain of the virus, with more diversity comes additional opportunities for hitting the genetic jackpot.

Perhaps there is some `species barrier' that prevents HPAI H5 from adapting well enough to humans to spark a pandemic, but it may just be that the right genetic combination (at the right time, and in the right place) hasn't emerged.

And if H5 fails to make the grade, there are scores of other subtypes (H6, H7, H9, H10, etc.) in the wings. The only thing that seems certain is that nature will keep trying.