#18,145

Over the years we've looked at a number of studies on the persistence of influenza A viruses - including avian H5N1 - in the environment. A few highlights include:

- In 2012's EID Journal: Persistence Of H5N1 In Soil, we looked at several studies that found H5N1 could remain viable on various surfaces, and in different types of soil, for up to 13 days (depending upon temperature, relative humidity, and UV exposure).

- In 2017, researchers showed that - when refrigerated - H5N1 infected poultry could remain infectious for months (see Appl Environ Microbiol: Survival of HPAI H5N1 In Infected Poultry Tissues).

- In 2020 we looked at a study from researchers at the USGS (see Proc. Royal Society B: Influenza A Viruses Remain Viable For Months In Northern Wetlands - USGS), which found long-term (up to 7 months) survival of influenza A viruses in wetlands in both Alaska and Minnesota.

- Last October in Emerg. Microbes & Inf.: Feather Epithelium Contributes to the Dissemination and Ecology of clade 2.3.4.4b H5 HPAI Viruses in Ducks, we saw evidence of `. . . environmental shedding and dissemination of H5 HPAIVs through the infected plumage of domestic ducks' which the authors warned `. . . may constitute an underestimated route of transmission'.

- And last month, in Viruses: Assessment of Survival Kinetics for Emergent Highly Pathogenic Clade 2.3.4.4 H5Nx Avian Influenza Viruses we looked at the survivability of 5 different HPAI H5 clade 2.3.4.4b viruses collected between 2014 and 2021, in a laboratory environment at 3 different temperatures (measured in days).

Additionally, in 2022 we saw a cautionary report in the EID Journal: Higher Viral Stability and Ethanol Resistance of Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus on Human Skin, that found H5N1 demonstrates an enhanced ability to survive on some surfaces, and is less affected by low concentrations of ethanol than than other common influenza subtypes.

This reputation for hardiness, in diverse conditions across a range of surfaces, is one of the reasons why the CDC has strongly urged the use of PPEs for farm workers who may be working with infected livestock.

Today the CDC's EID Journal has published an early release research letter which finds - not surprisingly - that the cattle-related H5N1 virus remains infectious in raw milk, and on milking machine surfaces, for hours and presents a genuine health hazard.

I've posted some excerpts below, but you'll want to follow the link to read the full report.

Research Letter

Persistence of Influenza H5N1 and H1N1 Viruses in Unpasteurized Milk on Milking Unit Surfaces

Valerie Le Sage1, A.J. Campbell1, Douglas S. Reed, W. Paul Duprex, and Seema S. Lakdawala

Author affiliations: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA (V. Le Sage, D.S. Reed, W.P. Duprex); Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA (A.J. Campbell, S.S. Lakdawala)

Abstract

Examining the persistence of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) from cattle and human influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic viruses in unpasteurized milk revealed that both remain infectious on milking equipment materials for several hours. Those findings highlight the risk for H5N1 virus transmission to humans from contaminated surfaces during the milking process.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus was detected in US domestic dairy cattle in late March 2024, after which it spread to herds across multiple states and resulted in at least 3 confirmed human infections (1). Assessment of milk from infected dairy cows indicated that unpasteurized milk contained high levels of infectious influenza virus (2; L.C. Caserta et al., unpub. data, https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.22.595317External Link).

Exposure of dairy farm workers to contaminated unpasteurized milk during the milking process could lead to increased human H5 virus infections. Such infections could enable H5 viruses to adapt through viral evolution within humans and gain the capability for human-to-human transmission.

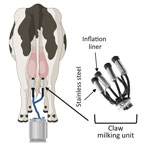

Figure 1. Illustration of milking unit surfaces tested in a study of persistence of influenza H5N1 and H1N1 viruses in unpasteurized milk. Before attaching the milking unit (claw), a dairy worker disinfects...

(SNIP)

We observed that the H5N1 cattle virus remained infectious in unpasteurized milk on stainless steel and rubber inflation lining after 1 hour, whereas infectious virus in PBS fell to below the limit of detection after 1 hour (Figure 2, panel A). That finding indicates that unpasteurized milk containing H5N1 virus remains infectious on materials within the milking unit.

To assess whether a less pathogenic influenza virus could be used as a surrogate to study viral persistence on milking unit materials, we compared viral decay between H5N1 and H1N1 in raw milk over 1 hour on rubber inflation liner and stainless-steel surfaces (Figure 2, panel B). The 2 viruses had similar decay rates on both surfaces, suggesting that H1N1 can be used as a surrogate for H5N1 cattle virus in studies of viral persistence in raw milk.

Further experiments examining H1N1 infectiousness over longer periods revealed viral persistence in unpasteurized milk on rubber inflation liner for at least 3 hours and on stainless steel for at least 1 hour (Figure 2, panel C). Those results indicate that influenza virus is stable in unpasteurized milk and that influenza A virus deposited on milking equipment could remain infectious for >3 hours.

Taken together, our data provide compelling evidence that dairy farm workers are at risk for infection with H5N1 virus from surfaces contaminated during the milking process.

To reduce H5N1 virus spillover from dairy cows to humans, farms should implement use of personal protective equipment, such as face shields, masks, and eye protection, for workers during milking. In addition, contaminated rubber inflation liners could be responsible for the cattle-to-cattle spread observed on dairy farms. Sanitizing the liners after milking each cow could reduce influenza virus spread between animals on farms and help curb the current outbreak.

Dr. Le Sage is a research assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh Center for Vaccine Research, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. Her research interests include elucidating the requirements for influenza virus transmission and assessing the pandemic potential of emerging influenza viruses.