Yellow/red particles of avian influenza A H5N1 virus particles.CDC & NIAID

Looking at the receptor binding profiles of recent avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses to see how well-adapted they are to causing infections in people (compared to birds). Humans and birds have different types and distributions of receptors to which influenza viruses can bind and cause infection. The hemagglutinin protein is responsible for the virus binding (or attaching) to host cells, which has to happen in order for infection to occur.

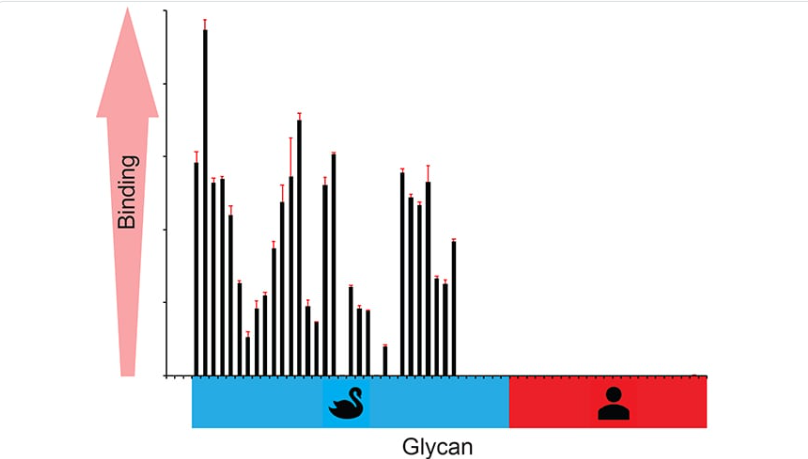

For the receptor binding analysis of A/Texas/37/2024, the hemagglutinin (HA) surface protein of the virus was expressed in the lab and tested for its ability to bind to both human- and avian-type receptors. Preliminary results from these studies show that the A/Texas/37/2024 hemagglutinin only binds to avian-type receptors, and not to human-type receptors. This means the virus's HA has not adapted to be able to easily infect people.

How well the A(H5N1) virus HA binds to avian-type, but not to human-type receptors is shown in the graph. Results from these studies indicate that this virus maintains a preference for avian-type receptors and is not adapting to be able to infect people.

Why these studies should come up with different results isn't clear, although it could boil down to differences in methods and materials.

Features of H5N1 influenza viruses in dairy cows may facilitate infection, transmission in mammals

H5N1 virus did not efficiently transmit via respiratory route to ferrets.

What

A series of experiments with highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza (HPAI H5N1) viruses circulating in infected U.S. dairy cattle found that viruses derived from lactating dairy cattle induced severe disease in mice and ferrets when administered via intranasal inoculation. The virus from the H5N1-infected cows bound to both avian (bird) and human-type cellular receptors, but, importantly, did not transmit efficiently among ferrets exposed via respiratory droplets. The findings, published in Nature, suggest that bovine (cow) HPAI H5N1 viruses may differ from previous HPAI H5N1 viruses and that these viruses may possess features that could facilitate infection and transmission among mammals.However, they currently do not appear capable of efficient respiratory transmission between animals or people.

In March 2024, an outbreak of HPAI H5N1 was reported among U.S. dairy cattle which spread across herds and led to fatal infections among some cats on affected farms, spillover into poultry, and four reported infections among dairy workers. The HPAI H5N1 viruses isolated from affected cattle are closely related to H5N1 viruses that have circulated in North American wild birds since late 2021. Over time, those avian viruses have undergone genetic changes and have spread throughout the continent causing outbreaks in wild birds and mammals—sometimes with mortality rates and suspected transmission within species.

To better understand the characteristics of the bovine H5N1 viruses, researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Japan’s Shizuoka and Tokyo Universities, and Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory conducted experiments to determine the ability of bovine HPAI H5N1 to replicate and cause disease in mice and ferrets, which are routinely used for influenza A virus studies. Ferrets are thought to be a good model for understanding potential influenza transmission patterns in people because they exhibit similar clinical symptoms, immune responses and develop respiratory tract infections like humans.

The researchers intranasally administered to mice doses of bovine HPAI H5N1 influenza of increasing strength (5 mice per dosage group), and then monitored the animals for body weight changes and survival for 15 days. All the mice that received the higher doses died of infection. Some of the mice that received lower doses survived, and those that received the lowest dose experienced no body weight loss and survived.

The researchers also compared the effects of the bovine HPAI H5N1 virus to a Vietnamese H5N1 strain that is typical of H5N1 avian influenza virus in humans and to an H1N1 influenza virus, both delivered intranasally to mice. The mice that received either the bovine HPAI H5N1 virus or the Vietnamese avian H5N1 virus experienced high virus levels in respiratory and non-respiratory organs, including in the mammary glands and muscle tissues, and sporadic detection in the eyes. The H1N1 virus was found only in the respiratory tissues of the animals. Ferrets intranasally infected with the bovine HPAI H5N1 virus experienced elevated temperatures and loss of body weight. As with the mice, the scientists discovered high virus levels in the ferrets’ upper and lower respiratory tracts and other organs. Unlike the mice, however, no virus was found in the ferrets’ blood or muscle tissues.

“Together, our pathogenicity studies in mice and ferrets revealed that HPAI H5N1 derived from lactating dairy cattle may induce severe disease after oral ingestion or respiratory infection, and infection by either the oral or respiratory route can lead to systemic spread of virus to non-respiratory tissues including the eye, mammary gland, teat and/or muscle,” the authors write.

To test whether bovine H5N1 viruses transmit among mammals via respiratory droplets, such as emitted by coughs and sneezes, the researchers infected groups of ferrets (four animals per group) with either bovine HPAI H5N1 virus or H1N1 influenza, which is known to transmit efficiently via respiratory droplets. One day later, uninfected ferrets were housed in cages next to the infected animals. Ferrets infected with either of the influenza viruses showed clinical signs of disease and high virus levels in nasal swabs collected over multiple days. However, only ferrets exposed to the H1N1-infected group showed signs of clinical disease, indicating that the cow influenza virus does not transmit efficiently via respiratory droplets in ferrets.

Typically, avian and human influenza A viruses do not attach to the same receptors on cell surfaces to initiate infection. The researchers found, however, that the bovine HPAI H5N1 viruses can bind to both, raising the possibility that the virus may have the ability to bind to cells in the upper respiratory tract of humans.

“Collectively, our study demonstrates that bovine H5N1 viruses may differ from previously circulating HPAI H5N1 viruses by possessing dual human/avian-type receptor-binding specificity with limited respiratory droplet transmission in ferrets,” the authors said.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health, funded the work of the University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers.

Article

A Eisfield et al. Pathogenicity and transmissibility of bovine H5N1 influenza virus in mice and ferrets. Nature DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07766-6) (2024).

The apparent poor transmission between co-housed ferrets (only 1 in 4 developed a sub-clinical infection) remains reassuring, however a recent CDC study (see Results of Ferret Transmission Studies on Texas H5N1 Virus), found 1-in-3 exposed ferrets were actively infected via this route.

In terms of spread, the CDC ferret study found that the A/Texas/37/2024 virus spread easily among ferrets (3 of 3 ferrets, or 100%) in direct contact with infected ferrets (placed in the same enclosure). However, the virus was less capable of spreading by respiratory droplets, which was tested by placing infected ferrets in enclosures next to healthy ferrets (with shared air but without direct contact).

In that situation, only 1 of 3 ferrets (33%) became infected, and there was a one- or two-day delay in transmission with the A/Texas/37/2024 virus compared to transmission with seasonal flu viruses. This suggests that A/Texas/37/2024-like viruses would need to undergo changes to spread efficiently by droplets through the air, such as from coughs and sneezes. CDC is repeating the experiment to confirm the findings and the results of these experiments will be used to inform an ongoing, broader CDC-led influenza risk assessment (IRAT) on A/Texas/37/2024.

When dealing with a relatively small cohort of test subjects (3 or 4 ferrets) it is not all that surprising that the results differ somewhat. Where they agree, however, is that the A/Texas/37/2024 strain remains nowhere near as transmissible (via the respiratory route) as seasonal flu viruses.

Of course, there are no guarantees how long that happy state of affairs will last.

While our attentions are understandably focused on A/Texas/37/2024, it is just one of scores of H5N1 genotypes circulating around the globe. They are joined by a panoply of other novel subtypes and clades, which have demonstrated similar zoonotic capabilities.

While an H5N1 pandemic may not be inevitable, another influenza pandemic will almost certainly emerge.

It's just a matter of when.