#18,272

Although I've been pretty diligent in wearing a surgical (or KN95) mask when in crowded public places for the past 4 years, I'll admit I don't usually doff the equipment as methodically as most infection control experts might like, and I often reuse masks (after UV exposure or 48 hours).

While I use hand sanitizer most of the time after removing my face covering, I'm not entirely consistent. But between my PPEs, my COVD/Flu vaccinations - and a little bit of luck - I've gone 3+ years without a COVID (or respiratory) infection.

Somewhat reassuringly, today we've a study in Nature that suggests that concerns over viral transfer from touching a contaminated face mask may be overblown. I've just posted some excepts, so follow the link to read it in its entirety.

Minimal influenza virus transmission from touching contaminated face masks: a laboratory study

Yuxuan Fan, Hidekazu Nishimura, Soichiro Sakata, Yasuhiro Okada, Satoru Ebihara, Julian W. Tang & Masahiro Kohzuki

Scientific Reports volume 14, Article number: 20211 (2024) Cite this article

The risk of virus transmission via the touching of contaminated masks has long been assumed by infection control teams. Yet, robust evidence to support this belief has been lacking. This risk was investigated in a laboratory setting by measuring the amount of viable influenza virus successfully transferred from artificially contaminated medical (surgical) mask surfaces to a human finger used to swipe their outer surface under various experimental conditions. Despite being exposed to high levels of virus contamination on the masks, very little or no viable virus was successfully transferred from the mask to the finger in these experiments.

Introduction

Respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been considered to spread through two major routes: by inhalation of aerosols or droplets and via direct or indirect contact with contaminated surfaces. The latter route has long been emphasized in the field of infection control. The touching of contaminated masks is also traditionally assumed to be a risk of viral transmission in hospital infection control practices for the prevention of nosocomial infection of influenza, as well as of other infectious diseases. However, there is a notable lack of evidence supporting this route of transmission, despite the amount of infection control guidance related to this, including various personal protective equipment (PPE) donning/doffing guidelines1.

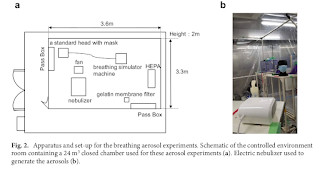

This study, conducted in a laboratory setting, investigates this risk for influenza transmission by quantitatively assessing the transfer of viable viruses from artificially contaminated medical (surgical) masks to human fingers. The surgical masks were exposed to airborne virus under differing experimental conditions, which mimicked common clinical exposure scenarios.

Results

Overall, with this experimental simulation, the number of transferred viruses was under the detection level or almost undetectable from the contaminated mask surfaces to the swiping finger. No virus or only a small amount (maximum 10 pfu) of the virus was detected in the experiments that used the nebulizer and coughing machine, which used large amounts of the virus under conditions reasonably favorable for influenza virus survival (20 °C, 20% RH) (Fig. 1a, b). Similarly, in the spray experiments under a variety of temperatures and RHs, little or no virus was detected on the swiping fingertip (Fig. 1c).

(SNIP)

It is notable that despite the viral loads used in these transmission experiments being very high compared to real-world settings, there was still little or no transmission via fingertip swiping. In addition, even if a very small amount of the virus were transferred to the fingertip or hand, their viability would decrease rapidly9,10. Furthermore, the transmission of influenza via fingers is thought to occur by contact of the contaminated fingertip with the nasal mucosal membrane, but the low infection efficiency by such a nasal route was also seen in data from an efficacy study for the influenza drug, oseltamivir11. Therefore, based on these study results, the risk of viral transmission via this fingertip-mask surface-touching route appears extremely low—in contrast to commonly cited infection control guidance.

While we agree that a ‘bundled’ approach to infection control may be effective in sending a single message of how to disinfect surfaces and maintain good hand hygiene, we believe that this can go too far, as was seen with the excesses of ‘hygiene theatre’ highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic12. At least one other real-world study showed little or no external mask viral contamination13. Thus, that study, together with the results in this current study and the plausible mechanisms discussed to explain these findings, are likely applicable to other human respiratory viruses that are also substantially airborne14,15.

This is not to say that hand-washing and fomite transmission precautions are not important. This study, together with another12, simply suggests that the risk of viral transmission via touching the surface of used masks is low.