#18,375

After going 6 months without an outbreak in commercial poultry, late last week Canada's Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) announced 3 HPAI H5 outbreaks in British Columbia (see Canada & U.S. Report Fall Uptick In H5N1 Outbreaks In Poultry).

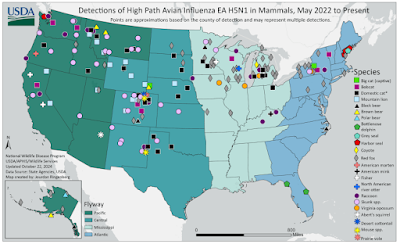

As we discussed two months ago, in Something Winged This Way Comes, we generally start seeing poultry and wild bird outbreaks in October as the annual southbound fall migration of birds from their northern latitude summer roosting areas reaches its peak.More than 200 bird species spend their summers in the Alaskan Arctic Refuge, and then funnel south each fall via 4 distinct North American Flyways (see map above). Alaska is also overlapped by the East Asian flyway, which may allow birds from Siberia and Mongolia to intermix with native migratory bird population (see USGS: Alaska - A Hotspot For Eurasian Avian Flu Introductions).

All of which means we can see occasional introduction of Asian avian viruses into our local bird populations, as well as incursions from European birds via the trans-Atlantic flyways (see Multiple Introductions of H5 HPAI Viruses into Canada Via both East Asia-Australasia/Pacific & Atlantic Flyways).

Over the past 5 days Canada's CFIA has announced 4 more outbreaks (see list below), 3 of which have occurred in the Fraser Valley (B.C) and 1 in Saskatchewan.

Since last Friday's report the USDA has also announced 4 relatively small outbreaks (in Washington State, Oregon & California) affecting fewer than 200,000 birds.

All of which reminds us that the amount of H5N1 in wild birds - and in the environment - continues to rise as we head into the fall and winter, and all flock owners (large and small) need to increase their biosecurity (see USDA's Defend the Flock).

And while we're currently seeing a lull in the reporting of mammalian wildlife with H5N1 (see map below), that number now officially exceeds 400, with dozens involving domestic cats and other peridomestic animals (see Virology: Susceptibilities & Viral Shedding of Peridomestic Wildlife Infected with Clade 2.3.4.4b HPAI Virus (H5N1)).

These reported cases are almost certainly a significant undercount as wild animals often die in remote and difficult to access places, and it appears that some states are prioritizing the testing of suspected cases more than others.

The CDC offers the following Advice for Pet Owners on avian flu:

While the risk of exposure to HPAI H5N1 from a companion animal or a wild bird is considered low, it is not zero, and it arguably goes up during the fall and winter months due to the arrival of migratory birds.

As a general precaution, people should avoid direct contact with wild birds and observe wild birds only from a distance, whenever possible. People should also avoid contact between their pets (e.g., pet birds, dogs and cats) with wild birds. Don't touch sick or dead birds, their feces or litter, or any surface or water source (e.g., ponds, waterers, buckets, pans, troughs) that might be contaminated with their saliva, feces, or any other bodily fluids without wearing personal protective equipment (PPE).More information about specific precautions to take for preventing the spread of bird flu viruses between animals and people is available at Prevention and Antiviral Treatment of Bird Flu Viruses in People. Additional information about the appropriate PPE to wear is available at Backyard Flock Owners: Take Steps to Protect Yourself from Avian Influenza.

While I hesitate to call this the `new normal', it is rapidly becoming our `new reality'.

One to which we'll need to adapt and adjust, if we hope to keep avian flu from becoming an even bigger threat.