#18,396

After going nearly a decade without reporting a human infection, Cambodia reported the first of 16 recent infections in February of 2023 (see graphic above), with nearly a 40% fatality rate (see WHO Update On Cambodian H5N1 Cases).

As we've often seen with H5N1, children and adolescents were the hardest hit.

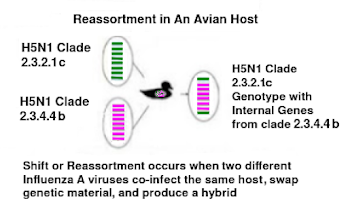

While Cambodia's avian flu resurgence came from an older (2.3.2.1c) clade of H5N1, last April in - FAO Statement On Reassortment Between H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b & Clade 2.3.2.1c Viruses In Mekong Delta Region - we learned that a new genotype - made up of this older clade and the newer 2.3.4.4b clade of H5N1 - had emerged in Southeast Asia.

The FAO wrote:In Asia, several clades continue to circulate, including A(H5N1) 2.3.4.4b, 2.3.2.1c and others, which can lead to reassortment and the appearance of viruses with new characteristics. A novel reassortant influenza A(H5N1) virus has been detected across the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), causing infections in both humans and poultry since mid- 2022.

This virus has recently caused human outbreaks in Cambodia early this year. This virus contains the surface proteins from clade 2.3.2.1c that has circulated locally, but internal genes from a more recent clade 2.3.4.4b virus.

The introduction and widespread circulation of this reassortant influenza A(H5N1) virus into the GMS poses a significant risk to both animal and human health, given the historical impact of HPAI outbreaks in the region. Further, this reassortment event indicates not only the adaptive capacity of the virus but also the ever-present risk of the emergence of new, potentially more virulent strains.

Although these reports indicated that humans and poultry had been infected by this new genotype, details on its emergence were scant. Today we have a preprint which seeks to fill in some of those gaps.

Emergence of a Novel Reassortant Clade 2.3.2.1c Avian Influenza A/H5N1 Virus Associated with Human Cases in Cambodia

Jurre Y Siegers, Ruopeng Xie, Alexander M P Byrne, Kimberly M Edwards, Shu Hu, Sokhoun Yann, Sarath Sin, Songha Tok, Kimlay Chea, Srey Viseth Horm, Chenthearath Rith, Seangmai Keo, Leakhena Pum, Veasna Duong, Heidi Auerswald, Yisuong Phou, Sonita Kol, Andre Spiegel, Ruth Harvey, Sothyra Tum, San Sorn, Bunnary Seng, Yi Sengdoeurn, Darapheak Chau, Savuth Chin, Makara Hak, Vanra Ieng, Sarika Patel, Han Di, Charles Todd Davis, Alyssa Finlay, Borann Sar, Peter M Thielen, Filip F Claes, Nicola S Lewis, Sovann Ly, Vijaykrishna Dhanasekaran, Erik A Karlsson

doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.11.04.24313747

Abstract

After nearly a decade without reported human A/H5N1 infections, Cambodia faced a sudden resurgence with 16 cases between February 2023 and August 2024, all caused by A/H5 clade 2.3.2.1c viruses. Fourteen cases involved a novel reassortant A/H5N1 virus with gene segments from both clade 2.3.2.1c and clade 2.3.4.4b viruses. The emergence of this novel genotype underscores the persistent and ongoing threat of avian influenza in Southeast Asia. This study details the timeline and genomic epidemiology of these infections and related poultry outbreaks in Cambodia.

(SNIP)

Phylogenetic analyses of each of the gene segments revealed that A/H5N1 viruses in Cambodia,detected from October 2023 onwards in both humans and poultry, represent a novel genotype resulting from reassortment. This reassortment combines segments from clade 2.3.2.1c (HA, NP, and NA) and clade 2.3.4.4b (PB2, PB1, PA, MP, and NS) viruses (Figure 2). In Cambodia, this novel 2.3.2.1c genotype has completely replaced the endemic 2.3.2.1c genotype that has dominated in poultry for the last decade.

(SNIP)

While the phenotypic contributions of newly introduced clade 2.3.4.4b internal gene segments have yet to be elucidated, the presence of amino acid mutations in both human and poultry viruses such as E627K in the 2.3.4.4b-origin PB2 gene segment suggests enhanced capacity for mammalian infection.

To better understand the zoonotic risk that these viruses pose, further risk assessment in silico, ex vivo, in vivo, and in vitro is critical. In addition, the detection of the PB2 627K mutation in poultry is also a concern, as it may become established in widespread circulation.

(SNIP)

In conclusion, these recurrent zoonotic infections caused by a novel reassortant A/H5N1 viruses in Cambodia serve as a reminder of the ever-present threat of AIV to global health security. Despite the recent focus on global dissemination and expanded host range of clade 2.3.4.4b 45-47 341 , clade 2.3.2.1c viruses remain a significant concern, particularly in Asia, where the two clades co-circulate.

A coordinated, regional approach is essential for effectively monitoring the threat of AIV and ensuring preparedness and response to emerging viral threats. Indeed, this study underscores the critical need and effectiveness of a unified, One Health approach to combat the evolving landscape of AIV. The urgency of this collaborative effort cannot be overstated as these viruses continue to adapt and reassort, increasing the risk of a strain evolving the capacity for efficient human-to-human transmission.

To stay ahead of this threat, we must prioritize sustainable funding for long-term surveillance, enhance laboratory capacity for rapid whole genome sequencing, and foster open, trust based information sharing across borders. Our collective preparedness today will determine our ability to protect global health tomorrow.

As we discussed in my last blog (see UK: HPAI H5N5 Rising), the threat from HPAI H5 comes from a large and growing array of related viruses, all of which are on their own evolutionary pathway, and any of which could become a global health threat.

Even if we get lucky, and H5 doesn't have what it takes to spark a pandemic, there's no lack of other contenders in the wild. Whether from an influenza virus, a coronavirus, `Disease X', another pandemic is inevitable.

Which is why, in 2021's PNAS Research: Intensity and Frequency of Extreme Novel Epidemics, researchers estimated our pandemic risk may increase 3-fold over the next few decades.