Last December the CDC's EID Journal published a dispatch which reveals this older clade was actually `. . . a previously unreported reassortant consisting of clade 2.3.2.1a, 2.3.4.4b, and wild bird low pathogenicity avian influenza gene segments'.

Since new genotypes can abruptly alter the behavior of a virus, they are important to monitor and analyze. Unfortunately, the timely sharing of genetic sequences is far less robust than we'd like.

Today we've a preprint, published on the bioRxiv server, which describes two feline H5N1 infections - collected since the 1st of the year from two households in Chhindwara, India - which closely match the H5 virus detected in the 2-year old child traveler returning to Australia nearly a year ago.

These feline isolates are described as being 99.2% homologous with the child's sample (albeit with with 27 mutations distributed across different gene segments), despite being retrieved nearly a year - and 1,000 km - apart (see map at top of post).

A finding that suggests this emerging triple-reassortant H5N1 virus has a fair degree of `fitness', and is likely far more widespread than we'd previously suspected.

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Clade 2.3.2.1a virus infection in domestic cats, India, 2025Ashwin Ashok Raut, Ashutosh Aasdev, Naveen Kumar, Anubha Pathak, Adhiraj Mishra, Prakriti Sehgal, Atul Pateriya, Megha Katare Pandey, Sandeep Bhatia, Anamika Mishra

doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.02.23.638954

Preview PDF

Abstract

In January 2025, the highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus clade 2.3.2.1a infection was detected in domestic cats and whole-genome sequencing of two cat H5N1 isolates was performed using the Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencing platform. Phylogenetic analysis revealed the circulation of triple reassortant viruses in cats.

Although cat viruses lacked classic mammalian adaptation markers they carried mutations associated with enhanced polymerase activity in mammalian cells and increased affinity for α2-6 sialic acid receptor suggesting their potential role in facilitating infection in cats. The identification of reassortant HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.2.1a viruses in domestic cats in India highlights the urgent need for enhanced surveillance in domestic poultry, wild birds, and mammals, including humans, to track genomic diversity and molecular evolution of circulating strains.

To identify the closest matching sequences in the entire GISAID database (https://platform.epicov.org/epi3/frontend#16d9ee), we conducted a BLAST analysis on all eight gene segments of the cat HPAI H5N1 viruses. The results showed a close match to an HPAI H5N1 detected in a traveler returning to Australia from India in 2024 (A/Victoria/149/2024, GISAID accession no. EPI_ISL_19156871; https://www.gisaid.org).

All gene segments closely matched this strain, except for the M gene (Appendix Table 2). A whole-genome comparison between these cat viruses and A/Victoria/149/2024 showed 99.2% homology, with 27 mutations distributed across different gene segments, including a PB1-F2 (66S) marker associated with enhanced replication and virulence of H5N1 viruses (Schmolke et al., 2011) (Appendix Table 3) indicating their distinctiveness.

(SNIP)

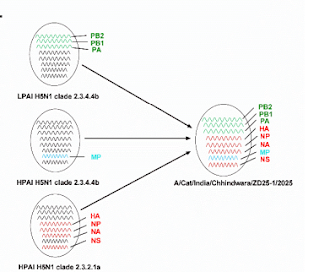

Phylogenetic analysis indicated that 102 A/Cat/Chhindwara/ZD25-1/2025(H5N1) and A/Cat/Chhindwara/ZD25-2/2025(H5N1) are reassortant viruses. Four gene segments (HA, NA, NP, and NS) were closely related to HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.2.1a viruses circulating in Bangladesh, while the remaining four segments (PB2, PB1, PA, and MP) clustered with clade 2.3.4.4b viruses (Figure 1 and Appendix Figures 1-4).

Notably, the matrix (MP) segment clustered with an HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b virus detected in a wild bird in South Korea (A/Bean goose/Korea/21WC198/2022), while the polymerase gene complex (PB2, PB1, and PA) grouped with low pathogenicity avian influenza (LPAI) H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b viruses that have been detected in poultry and wild birds in Asia since 2022 (Appendix 110 Figures 1-4).

These findings suggest that both HPAI and LPAI strains may have acted as intermediaries in donating internal genes to the HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.2.1a viruses detected in this study. It may be noted that H5N1 has been recently detected in wild felines (WOAH, 2025) and in poultry of the adjoining region in India (WOAH, 2025).

However, a comprehensive understanding of the spatiotemporal epidemiology across avian and mammalian hosts remains limited due to the paucity of H5N1 complete genomes from India. Currently, only three full genomes of H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b and 27 of H5N1 clade 2.3.2.1a viruses are available in GISAID, highlighting the need for expanded surveillance and genomic characterization.

While we are understandably focused on HPAI H5N1 in North America - and particularly on the B3.13 and D1.1 genotypes - there are hundreds of other H5 variants in the wild around the world, each on their own evolutionary path.

The vast majority will be biological failures, unable to compete with more `fit' viruses, and will fade away, often without our even noticing.

Today's study reminds us of how much goes on with HPAI outside of our field of vision.

That the next HPAI pandemic contender could emerge from anywhere in world; from sea lions in Argentina, rats in Egypt, cattle in North America, or cats in India.

Or from somewhere out of left field, where we haven't even started looking.