#18,360

Although the jury remains out on whether HPAI H5N1 can spark a human pandemic, it has already proven its ability to spread with devastating effects among birds and a growing number of mammalian hosts around the globe.

Six weeks ago, in Nature Reviews: The Threat of Avian Influenza H5N1 Looms Over Global Biodiversity, we looked at some of its recent impacts, including:

- The loss of nearly half a billion domestic fowl due to H5N1

- Likely close to a billion wild birds lost to the virus

- Hundreds of thousands of marine mammals (seals, sea lions, dolphins, etc.)

- And the loss of an unknown number of wild and peridomestic mammals

A few past blogs on this carnage among mammalian species include:

Travel Med. & Inf. Dis.: Pacific and Atlantic Sea Lion Mortality Caused by HPAI A(H5N1) in South America

EID Journal: Recent Changes in Patterns of Mammal Infection with Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Worldwide

EID Journal: Mass Mortality of Sea Lions Caused by HPAI A(H5N1) Virus (Peru)

We've seen smaller outbreaks from other avian flu viruses infect and kill marine mammals - including H3N8 in New England (2011), H10N8 in Germany (2014), and H5N8 in the Baltic Sea (2017) - but proving efficient mammal-to-mammal spread has always been a challenge.

Just over a year ago, however, we saw a Research letter in the EID Journal stating `. . . it seems likely that pinniped-to-pinniped transmission played a role in the spread of the mammal-adapted HPAI H5N1 viruses in the region.'

Cross-species and mammal-to-mammal transmission of clade 2.3.4.4b highly pathogenic avian influenza A/H5N1 with PB2 adaptations

Catalina Pardo-Roa, Martha I. Nelson, Naomi Ariyama, Carolina Aguayo, Leonardo I. Almonacid, Ana S. Gonzalez-Reiche, Gabriela Muñoz, Mauricio Ulloa, Claudia Ávila, Carlos Navarro, Rodolfo Reyes, Pablo N. Castillo-Torres, Christian Mathieu, Ricardo Vergara, Álvaro González, Carmen Gloria González, Hugo Araya, Andrés Castillo, Juan Carlos Torres, Paulo Covarrubias, Patricia Bustos, Harm van Bakel, Jorge Fernández, Rodrigo A. Fasce, . . . Rafael A. Medina Show authors

Nature Communications volume 16, Article number: 2232 (2025) Cite this article

Abstract

Highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses (HPAIV) belonging to lineage 2.3.4.4b emerged in Chile in December 2022, leading to mass mortality events in wild birds, poultry, and marine mammals and one human case.

We detected HPAIV in 7,33% (714/9745) of cases between December 2022–April 2023 and sequenced 177 H5N1 virus genomes from poultry, marine mammals, a human, and wild birds spanning >3800 km of Chilean coastline. Chilean viruses were closely related to Peru’s H5N1 outbreak, consistent with north-to-south spread down the Pacific coastline.

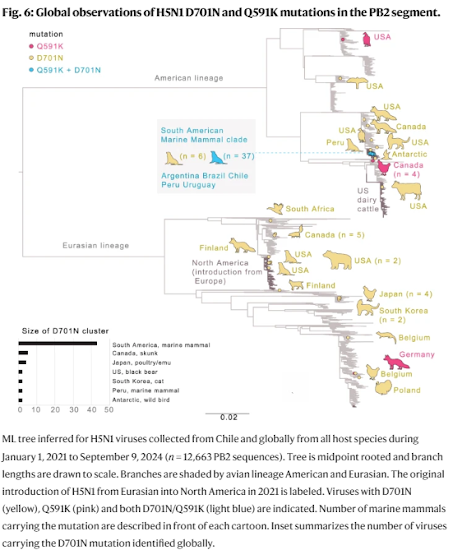

One human virus and nine marine mammal viruses in Chile had the rare PB2 D701N mammalian-adaptation mutation and clustered phylogenetically despite being sampled 5 weeks and hundreds of kilometers apart. These viruses shared additional genetic signatures, including another mammalian PB2 adaptation (Q591K, n = 6), synonymous mutations, and minor variants.

Several mutations were detected months later in sealions in the Atlantic coast, indicating that the pinniped outbreaks on the west and east coasts of South America are genetically linked. These data support sustained mammal-to-mammal transmission of HPAIV in marine mammals over thousands of kilometers of Chile’s Pacific coastline, which subsequently continued through the Atlantic coastline.

(SNIP)

Discussion

The emergence, spread and evolution of HPAIV H5N1 in South America since October 2022 has had a devastating impact on animal health and biodiversity. The Chilean authorities, between December 2022 and the first half of 2023, reported >62,300 wild birds and 17,294 penguins and marine mammal deaths associated with the outbreak. These included 14,987 South American sea lions, 10,971 Peruvian boobies, 8233 gulls (Larus sp.), 4.861 Peruvian pelicans, 2,235 Humboldt penguins, 34 marine otters, 22 Burmeister’s porpoises and 16 Chilean dolphins (https://www.sernapesca.cl/informacion-utilidad/registro-de-varamientos/, and https://www.sag.gob.cl/ia). By sequencing 177 H5N1 isolates, our study traces the origins of Chile’s massive multi-host epizootic, which appears to be closely connected to Peru’s HPAIV outbreak that was detected 1 month before Chile’s outbreak and caused similar mass die-offs in seabirds and marine mammals22.Our Bayesian phylodynamic analysis revealed the rapid north-to-south dissemination of HPAIV from Peru to Chile via wild bird movements during late 2022. This seeded the massive multi-host epizootic observed in Chile that caused severe disease in seabirds, birds of prey, commercial and backyard poultry, multiple species of marine mammals, as well as one human case. Importantly, wild birds appear to be the sole source of the poultry outbreaks as well as the marine mammal outbreak in Peru and Chile, and no connection was observed between the outbreaks in poultry and marine mammals (Figs. 3–5 and Supplementary Fig. 4). The clustering pattern of marine mammal viruses on the tree and the shared set of uncommon mutations supports a scenario in which the marine mammal outbreak in Peru and Chile was seeded by a single virus introduction from wild birds, and was the genesis of the subsequent mammal-to-mammal transmission spanning thousands of kilometers of Chile and Peru’s Pacific coastline during an 18 week period (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Mammal-to-mammal transmission of avian influenza viruses is suspected to have occurred in marine mammals on multiple occasions. Notable examples include a multi-country outbreak of avian H10N7 viruses affecting harbor seals in the North Sea (2014–2015)28, and an H5N1 an outbreak in marine mammals in New England, USA (2022)29. However, definite evidence has been difficult to establish due to the insufficient contemporary background sequence data from wild birds in these regions. One strength of our sampling strategy during the Chilean 2022-2023 HPAIV outbreak is the breadth and intensity of sampling across diverse wild bird species, including 31 avian orders, which helps contextualize the marine mammal viruses.At this level of wild bird sampling, one would expect more bird viruses interspersed with marine mammal viruses from Chile, including standard bird viruses that do not have the D701N or Q591K mutations (Supplementary Fig. 5). The position of one bird virus (A/sanderling/Arica y Parinacota/240265/2023) within the marine mammal clade was surprising, but the fact that this virus contains the D701N mutation, as well as other mutations observed in marine mammals and no other birds in Chile or Peru, is consistent with marine mammal-to-bird transmission, which is plausible given that shorebirds and sea lions share coastal habitat. The mutations found in marine mammals were also seen in the human case A/Chile/25945/2023, raising the possibility that marine mammals were the source of the one human H5N1 infection observed in Chile. Discerning the direction of transmission in this context is difficult, but the possibility of transmission between marine mammals and spillover to humans should be considered, warranting intensified monitoring of the fast-changing evolutionary trajectory of H5N1 along South America’s biodiverse coastlines.

(SNIP)

The concerning possibility of long-distance mammalian transmission of H5N1 in marine mammals in Chile warrants additional sequencing of H5N1 viruses in other South American countries, particularly from wild birds. While we cannot exclude other sources of infection in marine mammals, as more sequence data have become available from marine mammals outbreaks in other countries, including from Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil, where massive pinniped and sea bird die-offs were reported in September 2023, it has become apparent that the pinniped outbreaks on the west and east coasts of South America are truly genetically linked (this report and refs. 27,45,46).

Furthermore, the mammalian cluster in Chile contains viruses with the D701N or the double Q591K/D701N mutations, which contrasts to the marine mammal viruses seen later during the outbreaks in the Pacific coast of South America, where only the double Q591K/D701N mutant viruses have been observed since the second half of 2023. Whether the double Q591K/D701N mutation and/or the additional non-synonymous and synonymous mutations identified provide an evolutionary advantage to the virus (e.g. increased fitness in mammals) warrants further evaluation. Nonetheless, an underlying question highlighted during this outbreak is whether this novel reassorted genomic constellation of the B3.2 H5N1 South American clade, which contains PB2, PB1, NP, and NS segments from the American AIV lineage, provides an increased capability to generate the 701N and 591K mutations, and potentially other mammalian adaptations (Fig. 7).

Our analyses that this novel cluster likely arose first in Peru and Chile, and subsequently become fixed and was transmitted among Sea lions throughout the South American coastline27. Additional characterization of AIV sequences from 2023 and subsequent seasons will be crucial to determine whether reassorment events have occurred and assess if the dynamics and diversity of endemic strains have been modulated by the introduction of the B3.2 H5N1 lineage. Hence, continued surveillance and monitoring of the HPAIV outbreak in Chile, the Americas and Antarctica, along with experimental studies using in vitro and animal models to monitor phenotypic changes, are necessary to assess the risk posed by these H5N1 viruses and to inform public health authorities to improve pandemic preparedness and to control and protect human and animal populations during outbreak situations.

Although H5N1 has yet to crack the `transmission code' in humans, it has made remarkable progress infecting marine mammals in South America - and dairy cattle in the United States - and is no doubt honing its skills in other mammalian hosts around the world.

While its future successes are far from guaranteed, it requires a hefty dose of hubris to believe that we humans are somehow protected against a similar fate.