#18,742

Last February the Canada's PHAC Announced Plans To Purchase 500,000 doses Of H5N1 Vaccine, joining the ranks of the United States (4.8 million doses), the UK (5 million doses), Japan (10 million doses), and the EU (initially 664,000 doses but recently increased to 27+ million doses) who have all committed to major H5 vaccine purchases over the past 12 months.

With the exception of a special release of 20,000 doses of H5N1 vaccine to Finland following their fur-farm epizootic (see Finland: MOH Announcement On Avian Flu Vaccine Availability For People At High Risk), these vaccines reportedly remained locked away, as nations debate under what circumstances, and who would receive them.

In August of last year, Finland began a voluntary vaccination program (see THL Announces the Start Of H5 Vaccination For High Risk Groups) in hopes of preventing any potential H5N1/Seasonal flu co-infections which might lead to a reassortment event.

Finland was forced to quickly deploy their 20,000 doses of vaccine last year because it was near its expiration date. In the past we've seen stockpiled - and about to expire - H5N1 vaccines provided to high risk individuals in a similar `use it or lose it' strategy.

Hong Kong: H5N1 Vaccine Recommended For Certain Lab Workers

Japan Begins Pre-Pandemic Inoculation Of Health Care Workers

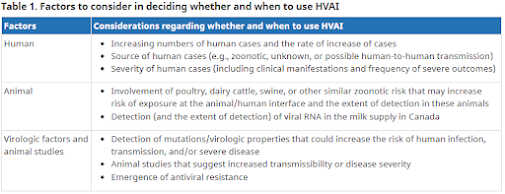

Last February, Canada's National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) released a detailed (38-page) set of preliminary guidance on the potential use of the H5N1 vaccine that considers when - and to whom - it might be appropriate to deploy an H5N1 vaccine during a pre-pandemic time period.

Today we have a commentary, published by the CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) which contemplates how, and when, local authorities might decide to utilize their recently ordered pre-pandemic stockpile of H5N1 vaccine.

This is obviously a discussion that is ongoing - albeit not always as publicly - in other countries as well.

I've only posted some extended excerpts, so follow the link to read the commentary in its entirety, including references.

Avian influenza and use of the H5N1 vaccine to prevent zoonotic infection in Canada

Alexandra Nunn, Angela Sinilaite, Bryna Warshawsky, Marina I. Salvadori, Isaac I. Bogoch and Winnie Siu

CMAJ June 02, 2025 197 (21) E599-E600; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.250641

Key points

- Outbreaks of avian influenza A(H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b viruses continue to be widespread among birds and poultry in many parts of the world, with transmission to mammals including humans in some countries and dairy cattle in the United States.

- These viruses are considered to have pandemic potential owing to their ability to infect and spread among mammals, their historically high mortality rate in humans, and the general lack of immunity in the human population.

- Although the current risk of infection for the public remains low, Health Canada recently authorized an H5N1 influenza vaccine that may benefit certain people with increased risk of exposure to the virus, such as those who work with the virus in laboratory settings or are involved in culling infected poultry, as an added layer of protection in addition to other preventive measures.

- Ongoing monitoring of the immune response to H5 influenza vaccines against circulating avian influenza strains will help to inform whether updated vaccines are needed.

In 2024 in the United States, avian influenza A(H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b was detected for the first time in dairy cattle, an unexpected and previously unrecognized host, with subsequent transmission to dairy farm workers. As dairy cattle and poultry farm outbreaks continue, reported human H5N1 infections in the US have risen to 70 cases and 1 death, primarily linked to occupational exposure. Less frequently, infections have also occurred through contact with infected backyard poultry flocks or from unidentified exposures.1

In Canada, the virus has been detected in wild birds in every province and territory, as well as in poultry and in wild mammals in most regions.2 Although the current risk of infection for the public remains low, people with prolonged or close (within 2 m) contact with infected animals or their secretions face a moderate risk of infection, and the potential for more severe infections is considered greater for children and immunocompromised adults.3 Health Canada recently authorized an H5N1 vaccine that may benefit certain people with increased risk of exposure to the virus, as an added layer of protection in addition to other preventive measures. We discuss historical and present patterns of H5N1 infection, the virus’s potential for pandemic spread among humans, and public health measures, including vaccination.

(SNIP)

In Canada, surveillance is ongoing to detect infections in dairy cattle, including milk testing, but to date, none have been found. Measures to prevent infection in people who work with infected animals include use of personal protective equipment, biosecurity protocols, and antiviral postexposure prophylaxis. Front-line health care providers should be familiar with risk factors for exposure to avian influenza, especially close or prolonged contact with infected farmed poultry, backyard flocks, or farmed or wild mammals or their environments. Influenza testing and isolation should be recommended for those with influenza-like illness and potential risk of avian influenza exposure.5

With respect to vaccination, in February 2025, Health Canada authorized a strain update to the Arepanrix H5N1 vaccine for use in people aged 6 months and older, with 2 doses administered at least 3 weeks apart.6 The vaccine targets the H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b viruses currently circulating in birds and mammals in North America. The Government of Canada purchased an initial 500 000 doses. Based on current evidence and expert opinion, Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) recommended to provincial and territorial health authorities that the vaccine could be considered for use in populations at increased risk of exposure to the virus, such as those who work with the virus in laboratory settings or those involved in culling infected poultry.7 Ultimately, the provinces and territories will decide how to deploy their allocated vaccine, guided by NACI recommendations, but the specific approaches are yet to be determined.

(SNIP)

As Canadian jurisdictions plan how they will use the current supply of H5N1 vaccine in the context of local risk conditions, experts continue to monitor and conduct research to fill existing knowledge gaps.9 Recent outbreaks and detections of avian influenza H5N2 and H5N5 in poultry in Canada raise the question of whether an H5N1 vaccine could provide protection against rapidly evolving avian influenza viruses. Limited evidence suggests that crossreactive immunity is expected from the H5 component of the vaccine, irrespective of the neuraminidase type, unless there is substantial evolution of the H5 of circulating strains. (The contribution of the neuraminidase components of vaccines to the immune response is an area of active scientific investigation.) A preprinted serologic study of a small sample of H5N8 vaccine recipients in Finland suggests that the vaccine elicited a good immune response to H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b viruses, representative of currently circulating strains.10 Ongoing monitoring of the immune response against circulating avian influenza strains will help to inform whether updated vaccines are needed.

(Continue . . . )