#18,798

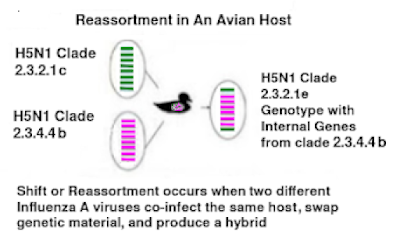

Influenza viruses are constantly evolving, and while most of these new iterations are evolutionary failures, occasionally a more biologically `fit' variant emerges, that is able to compete with older strains.Over the past two decades we've seen several major shifts in dominant H5 subtypes (H5N1 → H5N8 → H5N6 → H5N1), and a long procession of new clades and subclades.

Complicating matters, when these (and other influenza A viruses) infect a common host, they sometimes create a new hybrid (subtype, genotype, etc.) virus; aka a reassortment.

H5N5 reappeared during Europe's first major avian (H5N8) epizootic in 2017 (see Netherlands Finds 2 Dead Geese With HPAI H5N5). Although a relatively minor player, this newly emerged H5N5 virus was described as `highly aggressive' by Germany authorities.

Reports of H5N5 dwindled in 2018, but the subtype remerged in Russia in the fall of 2020, and began slowly spreading across Northern Europe (see Denmark Reports HPAI H5N5 In Peregrine Falcon).

A little over 2 years ago (May 2023), H5N5 appeared in Eastern Canada on Prince Edward Island (see CIDRAP Report Canada reports first H5N5 avian flu in a mammal).We checked back again in the spring of 2024 with HPAI H5N5: A Variation On A Theme, and with WAHIS: More Reports of HPAI H5N5 in Canada.

Last July, in Cell Reports: Multiple Transatlantic Incursions of HPAI clade 2.3.4.4b A(H5N5) Virus into North America and Spillover to Mammals, researchers reported finding the mammalian adaptive E627K mutation in a number of samples.

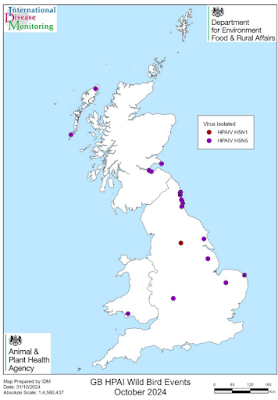

Thus, while A(H5N5) viruses are comparably uncommon, their high virulence and mortality potential demand global surveillance and further studies to untangle the molecular markers influencing virulence, transmission, adaptability, and host susceptibility.Last November, in UK: HPAI H5N5 Rising, we saw a sudden shift in H5N5 activity in wild birds in the UK, with the APHA reporting:

Since our previous outbreak assessment on 7 October 2024, there have been no new reports of high pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) H5 clade 2.3.3.4b in domestic poultry in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales). There have, however, been 15 more HPAI H5 clade 2.3.3.4b events involving 26 “found-dead” wild birds in Great Britain. Of these, 25 were HPAI H5N5 with 1 case of HPAI H5N1.

The plot thickened again last February when the UK Confirms HPAI H5N5 In 2 Grey Seals in Norfolk. In March the APHA confirmed even More Detections (n=13) of HPAI H5N5 In Seals, again in Norfolk.

While H5N5 continues to be overshadowed by H5N1, it has shown remarkable resilience, and continues to gain ground.All of which brings us to a preprint by researchers at the UK's APHA (Animal Plant Health Agency) on the co-circulation of HPAI H5N1 and H5N5 in wild seabirds and seals in the UK.

It also carries several worrisome mammalian adaptations (PB2-E627K and a 22-amino acid stalk deletion in NA) that may make it more of a threat to humans (and other mammals).

Co-circulation of distinct high pathogenicity avian influenza virus (HPAIV) subtypes in a mass mortality event in wild seabirds and co-location with dead seals

Marco Falchieri, Eleanor Bentley, Holly A. Coombes, Benjamin C. Mollett, Jacob Terrey, Samantha Holland, Edward Stubbings, Natalie Mcginn, Jayne Cooper, Samira Ahmad, Jonathan Lewis, Ben Clifton, Nick Collinson, James Aegerter, Divya Venkatesh, Debbie J. F. Russell, Joe James, Scott M. Reid, Ashley C. Banyard

doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.07.11.664278

Abstract

H5Nx clade 2.3.4.4b high pathogenicity avian influenza viruses (HPAIV) have been detected repeatedly in Great Britain (GB) since autumn 2020, with H5N1 dominating detections but with low level detection of H5N5 during 2025. Globally, these viruses have caused mass mortalities in captive and wild avian and mammalian populations, including terrestrial and marine mammals. H5N1 has been the dominant subtype, and whilst incursions have overlapped temporally, occurrences have often been spatially distinct.

Here, we report the detection of a mortality event in wild birds on the Norfolk coastline in the east of England, where H5N1 HPAIV was detected in five Great Black-backed Gulls (Larus marinus) and a Northern Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis).

Interestingly, at the same site, and as part of the same mortality event, a total of 17 Great Black-backed Gulls, one Herring Gull (Larus argentatus), one Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica) and one Northern Fulmar tested positive for H5N5 HPAIV. Additionally, H5N5 was also detected in 17 co-located Grey Seal carcases (Halichoerus grypus).

The H5N1 HPAIV from an infected bird belonged to genotype DI.2, closely related to contemporaneous detections in GB wild birds and poultry. In contrast, all H5N5 HPAIVs from birds and seals were genotype I with a 22-amino acid stalk deletion in NA and the 627K polymorphism in PB2. This represents the first recorded instance in GB of two subtypes being detected within the same avian population at the same location. It is also the first mass detection of HPAIV H5N5 in mammals within GB. Potential infection mechanisms are discussed.

(SNIP)

The co-circulation of distinct subtypes and genotypes within species occupying the same temporal, spatial and ecological landscapes raise important questions regarding the potential for viral reassortment and the role of gulls in the emergence of novel genotypes.

Numerous H5N1 genotypes have been described in each previous season dominated by H5N1 viruses, although a few genotypes were detected more frequently [35, 54]. Interestingly, since the beginning of the 2024/25 AIV season in GB, genotype diversity has been limited with DI.2 dominating positive avian detections [62].

Alongside DI.2, only the BB genotype, a previously dominant genotype, has been detected with some regularity, predominantly in the South-West of England in gull species that links with occasional detections in continental Europe [54]. Further, there have been two detections of the DI.1 genotype in wild birds in 2024, both have been of Norfolk, and it has not been detected since. Interestingly the contemporary H5N5 detections appear to be entirely represented by a single genotype (genotype I), with no evidence of reassortment.

Further, since the emergence of the H5N1 BB genotype in 2022, this has also exhibited predominately in gull species with limited reassortment. How and why different HPAIV genotypes are generated, and either dominate or disappear, remains a significant knowledge gap although several studies have demonstrated differential shedding and clinical impact in poultry species and it is likely that similar occurs in wild birds.

In conclusion, the detection of two subtypes, H5N1 and H5N5 in avian species linked to a mammalian mortality event that appears restricted to infection with a single H5N5 subtype is of high interest. Conditions for sampling carcasses were sub-optimal and the environmental conditions within which these detections were made precluded further swabbing and assessment.

Regardless, it is important to define and describe such detections as they clearly demonstrate that different viral subtypes can be present within a mortality event without reassortment being detected. Understanding the intra and inter-species infection and transmission dynamics is of high interest.

Globally there are scores of HPAI H5 variants (clades, subclades, subtypes, and genotypes), many circulating in multiple different hosts (e.g. marine mammals, livestock, peridomestic animals, wild birds and poultry) - each on their own evolutionary path.

But evolution never stops.