#18,870

As the CDC estimate for our most recent flu season (above) illustrates, our ability to identify, and track, influenza-related hospitalizations and deaths is limited. The CDC estimates somewhere between 27,000 and 130,000 deaths since October of 2024.

For the past 15 years the CDC has estimated the burden of seasonal flu using a mathematical model that uses data collected through the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network (FluSurv-NET); a network that covers only about 9% of the U.S. population.Complicating matters - flu-related deaths are not considered `reportable' unless they occur in pediatric patients - and even then only some percentage of deaths are likely captured. In the aftermath of the H1N1 pandemic of 2009, the CDC estimated the number of pediatric deaths in the United States likely ranged from 910 to 1880, or anywhere from 3 to 6 times higher than reported.

Which suggests that this year's record setting number of pediatric seasonal-flu related deaths is also likely an undercount.

While the exact numbers are hard to pin down, the 2024-2025 flu season now ranks as the most impactful flu season since 2010, with the highest estimated hospitalization rate in more than a decade.

Yesterday the CDC published a late-season recap in their weekly MMWR. I've reproduced some excerpts (follow the link to read it in its entirety). I'll have more after the break.

Influenza-Associated Hospitalizations During a High Severity Season — Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network, United States, 2024–25 Influenza Season

Weekly / September 11, 2025 / 74(34);529–537

Alissa O’Halloran, MSPH1; Jennifer Whitmill Habeck, MPH1,2; Matthew Gilmer, MS1,2; Ryan Threlkel, MPH1; Shua J. Chai, MD3,4; Brenna Hall, MPH3; Isaac Armistead, MD5; Nisha B. Alden, MPH5; James Meek, MPH6; Kimberly Yousey-Hindes, MPH6; Kyle P. Openo, DrPH7,8; Lucy S. Witt, MD7,8; Maya L. Monroe, MPH9; Patricia A. Ryan, MS9; Lauren Leegwater, MPH10; Sue Kim, MPH10; Melissa McMahon, PhD11; Ruth Lynfield, MD11; Khalil Harbi, MSPH12; Murtada Khalifa, MBBS13; Caroline McCahon13; Grant Barney, MPH14; Bridget J. Anderson, PhD14; Christina B. Felsen, MPH15; Brenda L. Tesini, MD15; Nancy E. Moran, DVM16; Denise Ingabire-Smith, MPH16; Melissa Sutton, MD17; M. Andraya Hendrick, MPH17; William Schaffner, MD18; H. Keipp Talbot, MD18; Andrea George, MPH19; Hafsa Zahid, MPH19; Shikha Garg, MD1; Catherine H. Bozio, PhD1 (VIEW AUTHOR AFFILIATIONS)View suggested citation

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

Seasonal influenza causes substantial annual U.S. morbidity and mortality.

What is added by this report?

Among a surveillance sample of the U.S. population, 2024–25 was a high severity influenza season. The cumulative influenza-associated hospitalization rate was the highest since 2010–11. During the 2024–25 season, the percentages of patients admitted to an intensive care unit (16.8%) and who received invasive mechanical ventilation (6.1%) were similar to past seasons’ estimates. Approximately one third of hospitalized patients were vaccinated. Children aged 5–17 years were the lowest percentage of hospitalized patients receiving antiviral treatment (61.6%).

What are the implications for public health practice?

All persons aged ≥6 months should receive an annual seasonal influenza vaccine. All hospitalized patients with suspected or confirmed influenza should receive timely antiviral treatment to reduce the risk for influenza-associated complications.

Full Issue PDF

Abstract

The U.S. 2024–25 influenza season was a high-severity season characterized by co-circulation of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) viruses. Data from the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network covering 9% of the U.S. population, were analyzed to compare laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalization rates and patient clinical characteristics from the 2024–25 season with data from past seasons.

Based on preliminary data from influenza-associated hospital admissions from October 1, 2024, through April 30, 2025, the cumulative influenza-associated hospitalization rate (127.1 influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population) had surpassed all end-of-season rates during the period beginning with the 2010–11 season.

Cumulative 2024–25 season rates were highest among persons aged ≥75 years (598.8). Across age groups, hospitalization rates during the 2024–25 season were 1.8 to 2.8 times higher than median historical rates during the period beginning with the 2010–11 season.

Among hospitalized patients, 32.4% had received an influenza vaccine, and 84.8% received antiviral treatment, though children and adolescents aged 5–17 years had the lowest proportion of antiviral receipt (61.6%). Similar to past seasons, most patients hospitalized with influenza during the 2024–25 season (89.1%) had one or more underlying medical conditions, 16.8% were admitted to an intensive care unit, 6.1% received invasive mechanical ventilation, and 3.0% died in hospital.

Seasonal influenza viruses can cause severe disease, particularly among persons who are at higher risk for complications. CDC recommends that all persons aged ≥6 months who do not have contraindications receive an annual influenza vaccine and that all hospitalized patients with influenza receive timely antiviral treatment to reduce the risk for complications.(SNIP)

High rates observed during the 2024–25 season could have been driven by recent lower influenza vaccination coverage in the general population (Weekly Flu Vaccination Dashboard | CDC), as well as virus characteristics. The distribution of 2024–25 influenza virus A subtypes might partially explain why, in contrast to other age groups, rates among persons aged ≥75 years were not the highest compared with past seasons.Since persons aged ≥75 years retain immunologic protection against A(H1) viruses from early childhood exposures, they have historically experienced more severe illness and death in A(H3N2)-predominant seasons (4). In 2017–18, the last season classified as highly severe for all age groups, circulating influenza A viruses were predominantly A(H3N2) (84%), whereas in 2024–25, both A(H3N2) and A(H1N1) viruses co-circulated equally (FluView Weekly Influenza Surveillance Report | CDC).Annual influenza vaccination for persons aged ≥6 months and early initiation of antiviral treatment for patients with influenza who are at higher risk for complications can help prevent adverse outcomes (5,6). Nonpharmacologic measures, such as hand washing, might also prevent transmission (6,7).

Seasonal flu is notoriously unpredictable - and a mild epidemic is always possible - but there are a few reasons to be concerned about the upcoming respiratory season.

- First, Australia has reported an unusually severe flu season (link), which Dr. Ian Mackay has chronicled in his Virology Down Under blog (see A Flunami in July).

- Second, two weeks ago Denmark reported An Unusually Early Major Outbreak of Influenza A (H1N1),which displayed unspecified `unique changes'.

- Third, the UK has seen a steady increase in flu severity over the past couple of seasons, with 2023 being more severe than 2022, and 2024 being more severe than 2023.

- Fourth, we've been following reports of a slow rise in antiviral resistant flu viruses for the past couple of years (see EID Journal: Multicountry Spread of Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 Viruses with Reduced Oseltamivir Inhibition, May 2023–February 2024).

All good reasons to get the seasonal flu shot this fall.

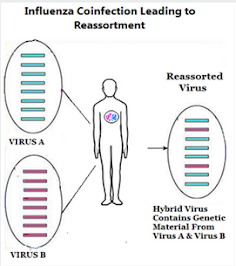

But to these, we can add one more; concerns over possible coinfection with seasonal flu and H5N1 (see Preprint: Intelligent Prediction & Biological Validation of the High Reassortment Potential of Avian H5N1 and Human H3N2 Influenza Viruses).

Antigenic `Shift' or Reassortment

It isn't just a theoretical concern; twice in my lifetime (1957 & 1968) avian flu viruses have done precisely that: reassorted with a seasonal flu virus and launched a human pandemic.

- The first (1957) was H2N2, which according to the CDC `. . . was comprised of three different genes from an H2N2 virus that originated from an avian influenza A virus, including the H2 hemagglutinin and the N2 neuraminidase genes.'

- In 1968 an avian H3N2 virus emerged (a reassortment of 2 genes from a low path avian influenza H3 virus, and 6 genes from H2N2) which supplanted H2N2 - killed more than a million people during its first year - and continues to spark yearly epidemics more than 50 years later.

While increased uptake of the flu vaccine isn't guaranteed to prevent this sort of untoward event, it should help reduce the chances.

While I recognize it probably only provides my age group with 30%-40% protection, given the long list of things that can go wrong during or following flu infection, I'll take whatever advantage I can get.

And if, perchance, it prevents a pandemic-inducing reassortment with HPAI H5 (not that we'll ever know), so much the better.