There once was a virus from Norway

That spread in a relative poor way

But since influenza can drift

or worse it could shift!

It could always discover one more way

# 5011

The not-unexpected news last week that the 2009 H1N1 virus has `drifted’ slightly (see Eurosurveillance On Recently Isolated H1N1 Mutations), and concerns over the still-rare `Norway’ mutation (see D222G And Deep Lung Infections), remind us that influenza is a moving target and that changes in the virus are not only possible . . . they are inevitable.

Last year, in the opening days of the pandemic, I described (see Pandemic Variables) the process this way.

A pandemic isn’t a static event, and the virus – carried simultaneously by millions of hosts – doesn’t change direction and speed in concert like a school of fish.

Instead, what you have are millions of hosts incubating trillions of virus particles – with mutational changes occurring all of the time. Most of these changes do not benefit the virus and lead nowhere, but out of trillions of rolls of the dice, some small number do.

It is survival – and propagation – of the biologically fittest.

Evolution in action.

With viruses that are better adapted to humans out-replicating, out-shedding, and out-transmitting lesser versions of the pandemic strain.

And that means that the virus we have in circulation today may not be the same virus we have running around in the fall, next winter, or next year sometime. We could potentially see changes in virulence or antiviral sensitivity over time.

Prophetic?

Hardly. This is a process that happens every year. Which is why we need a new, and updated, flu vaccine formulation each year.

Most of the time these changes are small, incremental, and have relatively little impact on virulence.

Rarely, as in the case of a pandemic, we see a major shift in the influenza virus, which can affect its severity or transmissibility (or both).

But a major shift doesn’t always spark a pandemic. On very rare occasions, the influenza virus can just temporarily go rogue.

Which brings us to one of the great medical mysteries of the last century: The largely unexplained, but nonetheless fascinating Liverpool Killer Flu of 1951.

This startling graphic comes from the March 16th, 1951 Proceedings of The Royal Society of Medicine – page 19 – and shows in detail the tremendous spike in influenza deaths in early 1951 over the (admittedly, unusually mild) 1948 flu season.

For most of the world, however, 1951 remained an average flu year. The dominate strain of influenza that year was the so-called `Scandinavian strain', which produced mild illness in most of its victims.

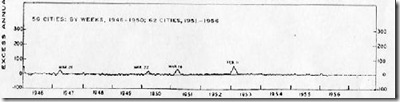

In fact, if you look at the graph for the United States, running from 1945 to 1956, you'll see nary a blip.

But in December of 1950 a new strain of virulent influenza appeared in Liverpool, England, and by the end of the flu season, had spread across much of England, Wales, Canada and even parts of the US.

The CDC's EID Journal has a stellar account of this 1951 evemt, and much of what follows I've gleaned from this report:

Viboud C, Tam T, Fleming D, Miller MA, Simonsen L. 1951 influenza epidemic, England and Wales, Canada, and the United States. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2006 Apr [date cited].

ABSTRACT

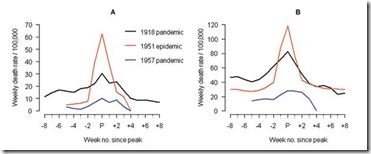

Influenza poses a continuing public health threat in epidemic and pandemic seasons. The 1951 influenza epidemic (A/H1N1) caused an unusually high death toll in England; in particular, weekly deaths in Liverpool even surpassed those of the 1918 pandemic.

We further quantified the death rate of the 1951 epidemic in 3 countries. In England and Canada, we found that excess death rates from pneumonia and influenza and all causes were substantially higher for the 1951 epidemic than for the 1957 and 1968 pandemics (by >50%).

The age-specific pattern of deaths in 1951 was consistent with that of other interpandemic seasons; no age shift to younger age groups, reminiscent of pandemics, occurred in the death rate. In contrast to England and Canada, the 1951 epidemic was not particularly severe in the United States.

Why this epidemic was so severe in some areas but not others remains unknown and highlights major gaps in our understanding of interpandemic influenza.

According to this study, the effects on the city of origin, Liverpool, were horrendous.

In Liverpool, where the epidemic was said to originate, it was "the cause of the highest weekly death toll, apart from aerial bombardment, in the city's vital statistics records, since the great cholera epidemic of 1849" (5). This weekly death toll even surpassed that of the 1918 influenza pandemic (Figure 1)

This extraordinary graph shows the excess deaths in Liverpool during this outbreak (red line), while the black line shows the peak deaths during the 1918 pandemic. This chart shows excess deaths by A) respiratory causes (pneumonia, influenza and bronchitis) and B) all causes.

For roughly 5 weeks Liverpool saw an incredible spike in deaths due to this new influenza. And it did not remain localized to Liverpool.

While it appears not to have spread as easily as the dominant Scandinavian strain, it managed to infect large areas of England, Wales, and Canada over the ensuing months.

The authors of this study describe the spread of this new influenza:

Geographic and Temporal Spread

Influenza activity started to increase in Liverpool, England, in late December 1950 (5,13). The weekly death rate reached a peak in mid-January 1951 that was ≈40% higher than the peak of the 1918–19 pandemic, reflecting a rapid and unprecedented increase in deaths, which lasted for ≈5 weeks [5 ] and Figure 1).

Since the early 20th century, the geographic spread of influenza could be followed across England from the weekly influenza mortality statistics in the country's largest cities, which represented half of the British population (13). During January 1951, the epidemic spread within 2 to 3 weeks from Liverpool throughout the rest of the country.

For Canada, the first report of influenza illness came the third week of January from Grand Falls, Newfoundland (19). Within a week, the epidemic had reached the eastern provinces, and influenza subsequently spread rapidly westward (19).

For the United States, substantial increases in influenza illness and excess deaths were reported in New England from February to April 1951, at a level unprecedented since the severe 1943-44 influenza season. Much milder epidemics occurred later in the spring elsewhere in the country (9).

For reasons we don't understand, this new strain never managed to spread much beyond England, Wales, Canada, and parts of New England.

It dissipated as suddenly as it appeared, failing to return the following year.

Whatever change or mutation sparked this sudden surge in virulence remains a medical mystery.

None of this is offered as a prediction as to what the H1N1 virus will do next. Frankly, I’ve no special insight into what the recently reported swine flu variant, or the `Norway D222G’ mutation will mean over time.

I present this bit of influenza lore simply because I find it intriguing, and it demonstrates that even seasonal flu can be a highly unpredictable, and oft times dangerous pathogen.

Even in a non-pandemic influenza season.