# 5582

With the 2010-2011 northern hemisphere flu season at its end, the World Health Organization has released a summary of global influenza trends over the past six months.

This summary appears in the latest Weekly Epidemiological Record 2011, 86, 221–232 and on the WHO’s Global Alert and Response (GAR) page.

I’ve excerpted a few passages (and reformatted for readability), but the entire report is worth reading. I’ll return with some brief comments:

Summary review of the 2010-2011 northern hemisphere winter influenza season

This review summarizes the chronology, epidemiology, and virology of the northern hemisphere temperate regions' winter influenza season encompassing the time period from October 2010 through the end of April 2011.

It is an expanded version of the WHO Weekly Epidemiological Record (WER) 27 May 2011, vol. 86 (pp 221-232).

Summary points

• The winter influenza season in the temperate countries of the northern hemisphere began in late October in Asia, a month later in Europe and North America, but was largely over by the end of April.

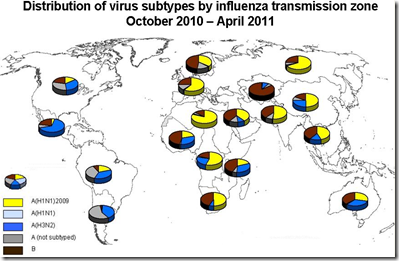

• The most commonly detected virus was different in North America, where influenza A(H3N2) and influenza type B co-circulated with influenza A(H1N1)2009, and Europe, where influenza A(H1N1)2009 was by far the most commonly detected virus.

• Although it was no longer the predominant influenza virus circulating in many parts of the world, H1N1 (2009) otherwise behaved much the same way as it had during the pandemic in terms of the age group most affect and the clinical pattern of illness.

• The impact of the influenza season in some areas where H1N1 (2009) was the predominant virus was more than in the previous year, most notably in the United Kingdom (UK) where intensive care units were stressed by large numbers of cases requiring ventilatory support.

• More than 90% of viruses detected around the world were similar antigenically to those found in the seasonal trivalent influenza vaccine.

• Antiviral resistance in influenza A(H1N1)2009 remained at a very low level. There were case reports with no history of exposure to antiviral medications, consistent with some community transmission of resistant virus.<SNIP>

Conclusions

Influenza A(H1N1)2009 continues to circulate widely. However in contrast to the pattern observed during the pandemic, the virus is now co-circulating with other influenza viruses and was not the predominant influenza A virus in many countries.

Circulation this season occurred during the expected influenza seasonal time frame with no out-of-season community transmission reported in temperate northern countries. The pattern of association between severe disease and age was similar to that observed previously.

Influenza A(H1N1)2009 continues to be more of a problem for young and middle-aged adults, while influenza A(H3N2) causes more severe disease in adults over the age of 65 years. Influenza type B appears to disproportionately affect young children.

A few countries appeared to have a higher number of severe cases compared to last year for reasons that are unclear. This was most notable in the UK though this observation may well be a surveillance artefact related to the active surveillance for severe disease that was carried out there.

All three circulating viruses demonstrated very little antigenic drift over the last year and were closely related to the three strains contained in the seasonal influenza vaccine. In addition, all but a very small percentage of viruses tested remain sensitive to neuraminidase inhibitors.

This reemphasises the need to continue to vaccinate and to treat early patients at high risk for developing severe disease, including those at the extremes of age, those with certain chronic medical illness, and pregnant women.

While admittedly a convoluted flu season, with four flu strains (five if you count the few remnants of seasonal H1N1) in circulation, and widely varying impacts around the world – some `good news’ stands out.

First, the feared rise in antiviral resistance for the 2009 H1N1 virus has not yet happened, with 98% of the samples testing still sensitive to oseltamivir.

However, since there were a few cases of oseltamivir resistance with no known exposure to the drug, concerns over possible limited community transmission of a resistant virus remain.

Second, while scattered mutations in the 2009 H1N1 virus have been detected, the vast majority of viruses tested remain antigenically similar to the current tri-valent influenza vaccine.

The chart below illustrates 99% of the H1N1 (2009) and 96% of the H3N2 viruses tested were antigenically similar to the current vaccine.

With two main lineages of B viruses that co-circulate each year, scientists must decide which strain to include in the vaccine. Some years they guess wrong, but this year nearly 91% of B viruses tested were a match (B Victoria) for vaccine strain.

While no guarantees can be made for what these influenza viruses will do in the next 6 to 12 months, for now they are behaving pretty much as scientists predicted.

The best news is that the vaccine being produced for the 2011-2012 flu season (Southern & Northern Hemisphere) appears to be an excellent match for 90% of the flu viruses currently circulating.

Of course, the only constant with influenza viruses is change.

And so we will watch the progress of the upcoming flu season south of the equator with great interest. What happens in Australia, New Zealand, South American, and South Africa can often tell us a lot about the kind of flu season we may see in the fall.

Stay tuned.