Reassorted viruses can result when two different flu strains inhabit the same host (human, swine, avian, or otherwise) at the same time. Under the right conditions, they can swap one or more gene segments and produce a hybrid virus.

# 8121

Southeast Asia has long been considered `the cradle of influenza’, an area of the world where both human and animal influenza viruses circulate more-or-less year round, among more than a billion humans who live in close proximity, and where humans and farm animals live in close contact with one another.

In other words, an ideal birthplace for new flu strains.

During the 20th century, 2 of the 3 major influenza pandemics (1957 Asian Flu, 1968 Hong Kong Flu) originated from this region. Additionally, the highly pathogenic `Asian’ version of H5N1 emerged from China in the mid-1990s, and last year, we saw the emergence of avian H7N9.

All of these viruses came to be through reassortment. A process where – over time - multiple parental viruses mix and match gene segments to create a new virus.

Reassorted viruses can result when two different flu strains inhabit the same host (human, swine, avian, or otherwise) at the same time. Under the right conditions, they can swap one or more gene segments and produce a hybrid virus.

While most reassortant viruses are evolutionary failures, and are unable to compete with the existing wild viruses, every once in awhile a new one appears that is both biologically fit, and capable of sparking an epidemic or pandemic. Which is why we watch novel influenza viruses – even those that appear to produce `mild’ illness in humans, carefully.

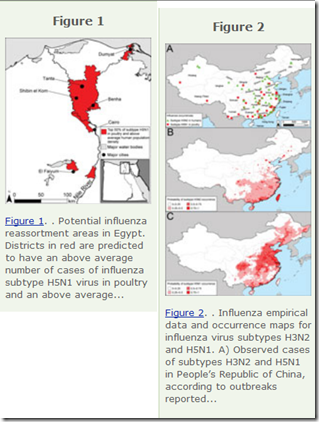

Last year, in EID Journal: Predicting Hotspots for Influenza Virus Reassortment, we looked at a study that identified 6 key geographic regions where reassortments are likely to emerge.

And high on that list (you guessed it), is Eastern mainland China.

Potential geographic foci of reassortment include the northern plains of India, coastal and central provinces of China, the western Korean Peninsula and southwestern Japan in Asia, and the Nile Delta in Egypt.

The authors conclude by writing:

The potential for reassortment between human and avian influenza viruses underscores the value of a One Health approach that recognizes that emerging diseases arise at the convergence of the human and animal domains (29,40).

Although our analysis focused on the influenza virus, our modeling framework can be generalized to characterize other potential emerging infectious diseases at the human–animal interface.

In 2013 alone, we saw the emergence of a new, highly pathogenic (in humans) avian flu strain called H7N9 in Eastern China, along with previously unrecognized lineage of the H7N7 virus (see Nature: Genesis Of The H7N9 Virus), and a never-seen-in-humans before H10N8 virus (see HK CHP Notified Of Fatal H10N8 Infection In Jiangxi). Just this week, Hong Kong reported a rare imported case of avian H9N2 infection, from Shenzhen.

And last May, Taiwan reported a never-seen-before human H6N1 infection.

Although our ears tend to perk up when we hear about one of these rare avian (or swine) viruses jumping to humans, we honestly don’t know how often it has happened over the years, and therefore we don’t have a good feel for how dangerous these reassortants really are.

Quite obviously, we’ve been watching the H5N1 virus making that jump to hundreds of humans over the past decade, and so far, the the virus has remained incapable sparking a pandemic. But with new clades (viral versions) appearing every year, the jury is still out on the H5N1 virus. How it will behave tomorrow, or next year, is unknown.

One of the prime parental contributors to the evolution of the H5N1 and H7N9 avian viruses is the H9N2 virus, which is endemic in poultry across much of Asia, and which has occasionally been known to infect humans. Recent studies (see PNAS: Reassortment Of H1N1 And H9N2 Avian viruses) have highlighted this virus’s ability to swap genes with other flu strains and produce viable reassortants.

Earlier this week, we saw a rare imported case of H9N2 in Hong Kong and today, we learn of another H9N2 infection, this time in Hunan Province China; that of a 7 year old boy who was sick, and recovered, in November. Here is the Hong Kong CHP notification:

CHP notified by NHFPC of human case of avian influenza A(H9N2) in Hunan

The Centre for Health Protection (CHP) of the Department of Health (DH) was notified by the National Health and Family Planning Commission today (January 2) of a human case of avian influenza A(H9N2) affecting a boy aged 7 in Hunan.

The patient, with poultry contact history, lived in Yongzhou, Hunan. He presented with fever and runny nose since November 19, 2013. He sought medical consultation from a hospital in Yongzhou the next day and recovered after treatment. This case was confirmed yesterday (January 1).

The CHP will liaise with the Mainland health authorities for more case details.

"We will remain vigilant and maintain liaison with the World Health Organization (WHO), the Mainland and overseas health authorities. Local surveillance activities will be modified according to the WHO's recommendations," the spokesman said.

"Travellers with fever or respiratory symptoms should immediately wear masks, seek medical attention and reveal their travel history to doctors," the spokesman advised.

The announcement of a second H9N2 case in less than a week out of mainland China is not particularly alarming, as this (and other) rare flu strains probably infect humans in China far more often than we know. It is likely that we are hearing of these cases more frequently simply due to the enhanced surveillance and testing that has been put into place since the emergence of H7N9 last spring.

But it is a reminder that these non-humanized flu strains are endemic in livestock and wild birds in many regions of the world, and can occasionally jump to humans or other species. Giving them increased opportunities to reassort with other flu viruses and to create new, potentially dangerous viral strains.

Which is why we watch reports, such as the one out of Hunan province today, for any signs that one of these viruses has picked up genetic changes that could increase its ability to create a public health threat.