Reassorted viruses can result when two different flu strains inhabit the same host (human, swine, avian, or otherwise) at the same time. Under the right conditions, they can swap one or more gene segments and produce a hybrid virus.

# 7589

It’s certainly been a busy day in Flublogia.

Out next stop is a study in the Journal Nature, off embargo about an hour ago (1pm EDT), that looks at the genesis of the H7N9 avian influenza virus in China, and along the way finds a previously unrecognized lineage of the H7N7 virus circulating in poultry as well.

Both the H7N9 and H7N7 viruses appear to be reassortants with the H9N2 virus, which is widespread in poultry throughout Asia.

Preliminary experiments with this newly discovered H7N7 strain show that this virus has the ability to infect, and replicate reasonably well, in ferrets – raising concerns that we may need to be watching more than just the H7N9 virus.

First a link to the Nature Article (alas, behind a pay wall), then a press release from the NIH which helped to fund this research, after which I’ll be back with more on H7 viruses.

Nature | Letter

The genesis and source of the H7N9 influenza viruses causing human infections in China

Tommy Tsan-Yuk Lam, Jia Wang, Yongyi Shen, Boping Zhou, Lian Duan, Chung-Lam Cheung, Chi Ma, Samantha J. Lycett, Connie Yin-Hung Leung, Xinchun Chen, Lifeng Li, Wenshan Hong, Yujuan Chai, Linlin Zhou, Huyi Liang, Zhihua Ou, Yongmei Liu, Amber Farooqui, David J. Kelvin, Leo L. M. Poon, David K. Smith, Oliver G. Pybus, Gabriel M. Leung, Yuelong Shu, Robert G. Webster et al.

ABSTRACT (EXCERPT)

The H7N9 outbreak lineage has spread over a large geographic region and is prevalent in chickens at live poultry markets, which are thought to be the immediate source of human infections. Whether the H7N9 outbreak lineage has, or will, become enzootic in China and neighbouring regions requires further investigation.

The discovery here of a related H7N7 influenza virus in chickens that has the ability to infect mammals experimentally, suggests that H7 viruses may pose threats beyond the current outbreak. The continuing prevalence of H7 viruses in poultry could lead to the generation of highly pathogenic variants and further sporadic human infections, with a continued risk of the virus acquiring human-to-human transmissibility.

From NIAID, we get the following press release.

NIH-Funded Scientists Describe Genesis, Evolution of H7N9 Influenza Virus

WHAT

:

An international team of influenza researchers in China, the United Kingdom and the United States has used genetic sequencing to trace the source and evolution of the avian H7N9 influenza virus that emerged in humans in China earlier this year. The study, published today in Nature, was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), a component of the National Institutes of Health, and other organizations.

Working in three Chinese provinces, researchers led by Yi Guan, Ph.D., of the University of Hong Kong collected samples from the throats and digestive tracts of chickens, ducks, geese, pigeons and quail. Fecal and water samples from live poultry markets and the natural environment were also collected. From these samples, the researchers isolated several influenza viruses and genetically sequenced those of the H7N9 subtype as well as related H7N7 and H9N2 viruses. These sequences were compared with archived sequences of the same subtypes isolated in southern China between 2000 and 2013. The researchers compared the differences between the two sets of sequences to reconstruct how the H7N9 virus evolved through various species of birds and to determine the origin of genes.

According to their analysis, domestic ducks and chickens played distinct roles in the genesis of the H7N9 virus infecting humans today. Within ducks, and later within chickens, various strains of avian H7N9, H7N7 and H9N2 influenza exchanged genes with one another in different combinations. The resulting H7N9 virus began causing outbreaks among chickens in live poultry markets, from which many humans became infected. Given these results, the authors write, continued surveillance of influenza viruses in birds remains essential.

While we’ve been watching the H5N1 virus with great care for more than a dozen years, scientists have also kept one eye on the H7 lineage of viruses (along with H9N2) as possible avian flu pandemic contenders.

We’ve been somewhat reassured because – at least until the H7N9 virus emerged this past spring – other H7 strains that have infected humans have typically only caused mild illness; often little more than sniffles and conjunctivitis.

Ten years ago, the largest known H7 cluster was recorded in the Netherlands. In that outbreak, the culprit was H7N7 (albeit from a different lineage than the H7N7 virus described in this Nature Journal letter).

Details on that cluster were reported in the December 2005 issue of the Eurosurveillance Journal.

Human-to-human transmission of avian influenza A/H7N7, The Netherlands, 2003

M Du Ry van Beest Holle, A Meijer, M Koopmans3 CM de Jager, EEHM van de Kamp, B Wilbrink, MAE. Conyn-van Spaendonck, A Bosman

An outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza A virus subtype H7N7 began in poultry farms in the Netherlands in 2003. Virus infection was detected by RT-PCR in 86 poultry workers and three household contacts of PCR-positive poultry workers, mainly associated with conjunctivitis.

Roughly 30 million birds residing on more than 1,000 farms were culled to control the outbreak. One person - a veterinarian who visited an infected farm – died a week later of respiratory failure.

The rest of the symptomatic cases were relatively mild.

The Fraser Valley H7N3 outbreak of 2004 resulted in at least two human infections, as reported in this EID Journal report:

Human Illness from Avian Influenza H7N3, British Columbia

Abstract

Avian influenza that infects poultry in close proximity to humans is a concern because of its pandemic potential. In 2004, an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza H7N3 occurred in poultry in British Columbia, Canada. Surveillance identified two persons with confirmed avian influenza infection. Symptoms included conjunctivitis and mild influenza like illness.

More recently, in Mexico we saw two mild human cases last summer (see see MMWR: Mild H7N3 Infections In Two Poultry Workers - Jalisco, Mexico). The World Health Organization published this Summary and assessment as of 10 September 2012.

Sporadic human cases of influenza A(H7N3) virus infection linked with outbreaks in poultry have been reported previously in Canada, Italy and the UK, with H7N2 in US and the UK, and with H7N7 in the UK and the Netherlands. Most H7 infections in humans have been mild with the exception of one fatal case in the Netherlands, in a veterinarian who had close contact with infected birds.

Of course – H7 flu strains - like all influenza viruses, are constantly mutating and evolving. What is mild, or relatively benign today, may not always remain so.

In 2008 we saw a study in PNAS that suggested the H7 virus might just be inching its way towards better adaptation to humans (see Contemporary North American influenza H7 viruses possess human receptor specificity: Implications for virus transmissibility).

You can read more about this in a couple of blogs from 2008, H7's Coming Out Party and H7 Study Available Online At PNAS.

The discovery of another H7 reassortant virus sharing some of the same parentage as H7N9 circulating in China isn’t terribly surprising, given the multitude of opportunities that flu viruses have to co-mingle among Chinese livestock.

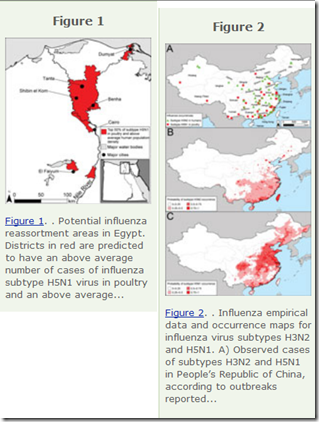

Last March, in EID Journal: Predicting Hotspots for Influenza Virus Reassortment, Eastern China was highlighted as one of the most favored areas in the world for seeing new influenza reassortants.

The study cited:

Potential geographic foci of reassortment include the northern plains of India, coastal and central provinces of China, the western Korean Peninsula and southwestern Japan in Asia, and the Nile Delta in Egypt.

All of which highlights the need for comprehensive and continual surveillance of farmed animals and wild birds, particularly in those regions of the world where these sorts of reassortments are most likely to occur.