# 8806

Chagas disease – caused by infection with Trypanosoma cruzi - is one of five parasitic diseases that have been declared by the CDC as being important Neglected Parasitic Infections in the United States. The other four are Cysticercosis, Toxoplasmosis, Toxocariasis, and Trichomoniasis.

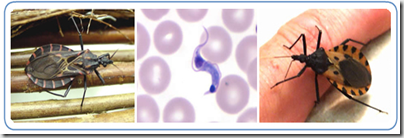

The parasite - Trypanosoma cruzi – is vectored by an infected triatomine bug (or "kissing bug"), an insect that takes blood meals from both humans and animals.

Of the estimated 300,000 infected individuals in the United States, nearly all are believed to have acquired the infection in Central or South America, although the type of bug capable of carrying the disease can be found in this country as well.

While the CDC reports there are 11 species of triatomine bugs that have been found the southern United States, the risks of contracting Chagas within the United States is considered very low. The CDC explains:

In areas of Latin America where human Chagas disease is an important public health problem, the bugs nest in cracks and holes of substandard housing. Because most indoor structures in the United States are built with plastered walls and sealed entryways to prevent insect invasion, triatomine bugs rarely infest indoor areas of houses.

Across Mexico, Central America, and South America an estimated 8 million people are infected, although most are unaware of their condition. During the acute phase of their infection many will show no symptoms, but some may experience fever, fatigue, body aches, headache, rash, loss of appetite, diarrhea, and vomiting and a characteristic swelling of the eyelids (Romaña's sign) for a period of a few weeks

Left untreated, the infection can progress to chronic condition, which the CDC describes as:

During the chronic phase, the infection may remain silent for decades or even for life. However, some people develop:

- cardiac complications, which can include an enlarged heart (cardiomyopathy), heart failure, altered heart rate or rhythm, and cardiac arrest (sudden death); and/or

- intestinal complications, which can include an enlarged esophagus (megaesophagus) or colon (megacolon) and can lead to difficulties with eating or with passing stool.

The average life-time risk of developing one or more of these complications is about 30%.

.

Although primarily vectored by infected triatomine bugs, they infection can also be acquired through:

- congenital transmission (from a pregnant woman to her baby);

- blood transfusion;

- organ transplantation;

- consumption of uncooked food contaminated with feces from infected bugs; and

- accidental laboratory exposure.

Up until recently, there was little concern over contracting Chagas disease from triatomine bugs in the United States, as they were believed to rarely take blood meals from humans. In 2012, in an EID Journal Dispatch, researchers found that 38% of (an admittedly small sample) of triatomine bugs tested in Arizona and California had fed on human blood.

Vector Blood Meals and Chagas Disease Transmission Potential, United States

Lori Stevens , Patricia L. Dorn, Julia Hobson, Nicholas M. de la Rua, David E. Lucero, John H. Klotz, Justin O. Schmidt, and Stephen A. Klotz

Abstract

A high proportion of triatomine insects, vectors for Trypanosoma cruzi trypanosomes, collected in Arizona and California and examined using a novel assay had fed on humans. Other triatomine insects were positive for T. cruzi parasite infection, which indicates that the potential exists for vector transmission of Chagas disease in the United States.

Last year, in Autochthonous Transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi, Louisiana, the EID Journal reported on a likely local infection with T. cruzi in Louisiana.

Abstract

Autochthonous transmission of the Chagas disease parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi, was detected in a patient in rural New Orleans, Louisiana. The patient had positive test results from 2 serologic tests and hemoculture. Fifty-six percent of 18 Triatoma sanguisuga collected from the house of the patient were positive for T. cruzi by PCR.

The Chagas parasite can be carried by a wide variety of mammalian hosts, including raccoons, opossums, armadillos, foxes, skunks, dogs, wood rats and squirrels, giving it plenty of indigenous hosts to inhabit, waiting to be vectored by a hungry triatomine bug.

All of which serves as prelude to a new study, just published in the EID Journal, that seeks to use shelter dogs as sentinels for the prevalence of Chagas disease in the United States.

Shelter Dogs as Sentinels for Trypanosoma cruzi Transmission across Texas

Trevor D. Tenney, Rachel Curtis-Robles, Karen F. Snowden, and Sarah A. Hamer

Author affiliations: Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, USA

Abstract

Chagas disease, an infection with the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, is increasingly diagnosed among humans in the southern United States. We assessed exposure of shelter dogs in Texas to T. cruzi; seroprevalence across diverse ecoregions was 8.8%. Canine serosurveillance is a useful tool for public health risk assessment.

Conclusions

Shelter dogs had widespread exposure to T. cruzi across 7 ecologic regions in Texas, with a conservative statewide average of 8.8% seroprevalence. The presence of seropositive dogs across all sampled regions, age classes, breed groups, and canine origins suggests that ecologic requirements for parasite transmission to dogs are not constrained to focal areas or particular breed groups. Although the travel histories of dogs in our study are unknown, the presence of antibodies in dogs across all age classes, including young dogs that are less likely to have traveled, suggests local exposure.

<SNIP>

Dogs that arrive at shelters, especially stray dogs, are likely to have had increased exposure to the outdoors and vectors and have been shown to have higher exposure to vectorborne pathogens than client-owned dogs that are brought to veterinary clinics (16). Shelter dogs, therefore, provide a sensitive population for assessment of local canine transmission risk, and we suggest that awareness of kissing bugs and Chagas disease risk among citizens and the medical community should be heightened in areas where seropositive dogs are detected.

For now, autochthonous transmission of Chagas disease in the United States remains a rare diagnosis, although it is also likely an under-reported disease. With changes to our climate and increased incursion of mankind into areas where wildlife (and triatomine bugs) may carry this parasite, the possibility exists that the number of locally acquired cases will increase in the future.

Making the development of sentinel surveillance techniques, such as described above, of growing importance.