Credit CDC

# 8867

Two and a half years ago the influenza world was rocked by news of the detection of a new subtype of influenza A (H17N10), found to reside in little yellow-shouldered bats captured in Guatemala (see A New Flu Comes Up To Bat). While bats are known to carry other zoonotic diseases, this was the first time that bats were linked to influenza A.

Since then, another previously unknown subtype (H18N11) has been identified, again in South American Bats (see PLoS Pathogens: New World Bats Harbor Diverse Flu Strains), leading to speculation that these mammalian-adapted flu viruses might someday jump to other species – including man.

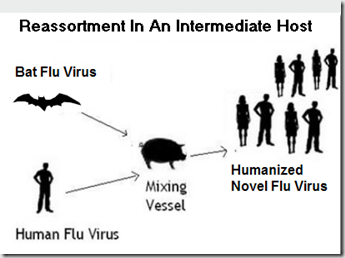

The most likely scenario for this to occur would be through the reassortment of a bat and a human virus in an intermediate host, such as a pig.

The CDC’s Bat Flu Q & A has this to say about the possibility of such a reassortment occurring:

However, the conditions needed for reassortment to occur between human influenza viruses and bat influenza virus remain unknown. A different animal (such as pigs, horses or dogs) would need to serve as a “bridge,” meaning that such an animal would need to be capable of being infected with both this new bat influenza virus and human influenza viruses for reassortment to occur. Additional studies are needed to determine the likelihood that reassortment would occur in nature between bat and human influenza viruses.

We’ve some reassuring news via Nature Communications on this front, suggesting that Bat Flu – at least from the H17N10 subtype – may have a difficult time making the leap from chiropterans to humans.

Since researchers have been unable to isolate and replicate the full H17N10 virus from bats, a chimeric (hybrid) virus was created for this study utilizing six internal genes from the bat virus, combined with the HA and NA or prototypic influenza A viruses

.

Mindaugas Juozapaitis, Étori Aguiar Moreira, Ignacio Mena, Sebastian Giese, David Riegger, Anne Pohlmann, Dirk Höper, Gert Zimmer, Martin Beer, Adolfo García-Sastre & Martin Schwemmle

Published 23 July 2014

In 2012, the complete genomic sequence of a new and potentially harmful influenza A-like virus from bats (H17N10) was identified. However, infectious influenza virus was neither isolated from infected bats nor reconstituted, impeding further characterization of this virus.

Here we show the generation of an infectious chimeric virus containing six out of the eight bat virus genes, with the remaining two genes encoding the haemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins of a prototypic influenza A virus. This engineered virus replicates well in a broad range of mammalian cell cultures, human primary airway epithelial cells and mice, but poorly in avian cells and chicken embryos without further adaptation.

Importantly, the bat chimeric virus is unable to reassort with other influenza A viruses. Although our data do not exclude the possibility of zoonotic transmission of bat influenza viruses into the human population, they indicate that multiple barriers exist that makes this an unlikely event.

The past few years have been busy ones for Chiroptologists.

Roughly 1/4th of all mammal species on earth are bats, and they are increasingly being viewed as naturals hosts for, and potential vectors of, a number of newly recognized emerging pathogens.

Once mainly feared for carrying rabies, in the 1990s bats gained notoriety with the emergence of the Hendra virus in Australia in 1994 (see Australia: Hendra Vaccine Hurdles) and Nipah in Malaysia in 1999 (see MMWR Update: Outbreak of Nipah Virus -- Malaysia and Singapore, 1999).

The emergence of the SARS coronavirus in 2003 – ultimately linked to bats – and most recently, to the MERS coronavirus in the Middle East (see EID Journal: Detection Of MERS-CoV In Saudi Arabian Bat), has served to cement their reputation as important carriers of emerging infectious diseases.

None of this is meant to demonize bats, as they play an important role in our ecosystem. However, bats are increasingly being associated with diseases deadly to humans, so a degree of caution is warranted.

To learn how you can stay safe around bats, the CDC offers the following advice.