# 8940

Five days ago (Aug 7th) the CDC released a revised Case Definition for Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) which I covered here. As has been pointed out before, case definitions and other guidance documents are based on the CDC’s current understanding of a particular pathogen – but they not static – and they can be expected to evolve as more is learned about any given threat.

In this latest guidance, the CDC set forth three categories of potential exposure; High Risk, Low Risk, and No Known Exposures.

The High Risk exposures are the ones we have all heard about time and again:

High risk exposures

A high risk exposure includes any of the following:

- Percutaneous, e.g. the needle stick, or mucous membrane exposure to body fluids of EVD patient

- Direct care or exposure to body fluids of an EVD patient without appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE)

- Laboratory worker processing body fluids of confirmed EVD patients without appropriate PPE or standard biosafety precautions

- Participation in funeral rites which include direct exposure to human remains in the geographic area where outbreak is occurring without appropriate PPE

The CDC also listed Low Risk exposures, and over the past day or so have caused quite a stir on the Internet, with charges that this is some kind of `admission’ that Ebola is an airborne virus.

It isn’t, but that hardly matters if your primary goal is to drive web traffic.

First, let’s look what the CDC considers to be Low Risk exposure:

A low risk exposure includes any of the following

- Household member or other casual contact1 with an EVD patient

- Providing patient care or casual contact1 without high-risk exposure with EVD patients in health care facilities in EVD outbreak affected countries*

The term `casual contact’ is defined as:

a) being within approximately 3 feet (1 meter) or within the room or care area for a prolonged period of time (e.g., healthcare personnel, household members) while not wearing recommended personal protective equipment (i.e., droplet and contact precautions–see Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations); or

b) having direct brief contact (e.g., shaking hands) with an EVD case while not wearing recommended personal protective equipment (i.e., droplet and contact precautions–see Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations).

At this time, brief interactions, such as walking by a person or moving through a hospital, do not constitute casual contact.

For the record, airborne viruses transmit well beyond a 1 meter radius of a patient. This 1 meter zone is basically within `spittle range’, where large droplets of mucus, blood, sweat, or other bodily fluids could potentially be coughed, sneezed, or otherwise propelled or flung onto another person.

While these risks may be considered low, they are not zero, and so it is important that people understand them. Still, to be infectious, a person has to be both infected, and symptomatic. And the odds of being exposed to someone outside of the `hot zones’ in West Africa right now are very slim.

There is actually another type of transmission, not really addressed here, and that is through fomites - surfaces or objects that an infected person might contaminate with body fluids - that could later infect someone else.

The trouble with including fomite exposure as an exposure risk is - unless you knew you’d been in a room with an Ebola patient (already covered above under Low risk) - you’d have no reason to suspect you’d touched a contaminated surface.

While I took exception to what I considered to be an overly simplistic infographic last week on Ebola transmission risks (see The Ebola Sound Bite & The Fury), I consider these guidelines – based on what we currently know about the Ebola virus – to be quite reasonable.

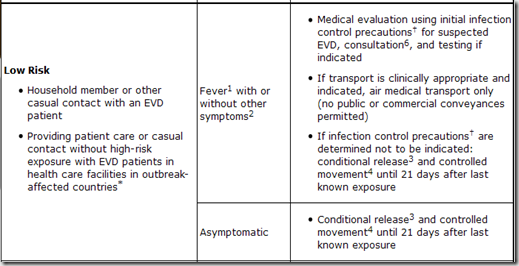

As far as what should be done about people who fall into either High Risk or Low Risk Exposure groups, the CDC has released the following tables in a document called Interim Guidance for Monitoring and Movement of Persons with Ebola Virus Disease Exposure.

* Outbreak-affected countries include Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone as of August 4, 2014

1 Fever: measured temperature ≥ 38.6°C/ 101.5°F or subjective history of fever

2 Other symptoms: includes headache, joint and muscle aches, abdominal pain, weakness, diarrhea, vomiting, stomach pain, lack of appetite, rash, red eyes, hiccups, cough, chest pain, difficulty breathing, difficulty swallowing, bleeding inside and outside of the body. Laboratory abnormalities include thrombocytopenia (≤150,000 /µL) and elevated transaminases.

3 Conditional release: Monitoring by public health authority; twice-daily self-monitoring for fever; notify public health authority if fever or other symptoms develop

4 Controlled movement: Notification of public health authority; no travel by commercial conveyances (airplane, ship, and train), local travel for asymptomatic individuals (e.g. taxi, bus) should be assessed in consultation with local public health authorities; timely access to appropriate medical care if symptoms develop

5 Self-monitor: Check temperature and monitor for other symptoms

6 Consultation: Evaluation of patient's travel history, symptoms, and clinical signs in conjunction with public health authority