Variability of Flu Seasons - Mash up from Multiple FluView Reports

# 9311

Most people are aware that over the past century we’ve seen 4 influenza pandemics; the 1918 Spanish Flu, the 1957 Asian Flu, 1968 Hong Kong Flu & the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Of these, the 1918 pandemic was (by far) the worst, but each of the others exacted a heavy toll as well.

Less well known have been the `rogue’ flu years, when we saw something less than a pandemic, but something substantially worse than a typical flu season.

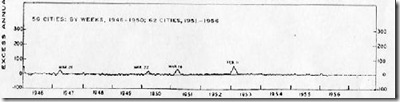

There is, of course, a good deal of variance between `normal’ flu seasons (see chart above), with significant jumps in P&I (Pneumonia & Influenza) mortality registered in the years 2000, 2003 and 2013, while 2012 was the mildest year for influenza in decades.

As a paramedic, I worked the `pseudo-pandemic’ of 1977, and I can attest that it had a big impact, even if it didn’t rise to the level of a global pandemic. In that case, an old nemesis – H1N1 – which had disappeared 20 years earlier after the arrival of H2N2 in the 1957 pandemic, came back.

While the exact mechanism of that virus’ return isn’t known, the strain was so similar to one last seen in the 1950s that it has been postulated that it was the result of an accidental lab release in China or Russia (see PLoS ONe The Re-Emergence of H1N1 Influenza Virus in 1977 . . . ). Hence, it was dubbed the `Russian Flu’.

Those over the age of 20 (I made the cut by 3 years), carried some immunity to the old H1N1 virus, but children and adolescents born after 1957 did not, and so they were the most susceptible to infection. Emergency rooms were slammed, and while the impact was limited and most patients recovered, in some people’s books 1977 qualifies as a `pseudo-pandemic’ year . . . at least for kids.

H1N1’s impact went far beyond just what happened in 1977, for for the first time in our limited knowledge of influenza strains, we ended up having two seasonal influenza A strains in co-circulation; H3N2 and H1N1. Something that previously, had never been observed.

Another, less well remembered event, was the `Liverpool Flu’ of 1951, which for awhile, killed at a greater rate than did the Great Influenza of 1918.

For most of the world, 1951 was an average flu year. The dominant strain of influenza that year was the so-called `Scandinavian strain', which produced mild illness in most of its victims. In fact, if you look at a graph of flu activity for the United States, running from 1945 to 1956, you'll see nary a blip.

But in December of 1950 a new strain of virulent influenza appeared in Liverpool, England, and by the end of the flu season, had spread across much of England, Wales, and Canada. This from an absolutely fascinating EID Journal article: Viboud C, Tam T, Fleming D, Miller MA, Simonsen L. 1951 influenza epidemic, England and Wales, Canada, and the United States.

The 1951 influenza epidemic (A/H1N1) caused an unusually high death toll in England; in particular, weekly deaths in Liverpool even surpassed those of the 1918 pandemic. . . . . Why this epidemic was so severe in some areas but not others remains unknown and highlights major gaps in our understanding of interpandemic influenza.

According to this study, the effects on the city of origin, Liverpool, were horrendous.

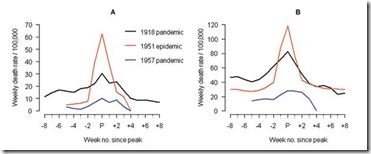

In Liverpool, where the epidemic was said to originate, it was "the cause of the highest weekly death toll, apart from aerial bombardment, in the city's vital statistics records, since the great cholera epidemic of 1849" (5). This weekly death toll even surpassed that of the 1918 influenza pandemic (Figure 1)

This extraordinary graph shows the excess deaths in Liverpool during this outbreak (red line), while the black line shows the peak deaths during the 1918 pandemic. This chart shows excess deaths by A) respiratory causes (pneumonia, influenza and bronchitis) and B) all causes.

For roughly 5 weeks Liverpool saw an incredible spike in deaths due to this new influenza. And it didn’t remain localized. While it appears not to have spread as easily as the dominant Scandinavian strain, it managed to infect large areas of England, Wales, and Canada over the ensuing months.

Getting started relatively late in the flu season, this new strain never managed to spread much beyond UK and Eastern Canada. Nor did it reappear the next flu season. It vanished as mysteriously as it appeared.

Another example, but one that affected the transmissibility and not the virulence of the seasonal virus, occurred in 1947. The so-called `vaccine failure’ year, when a new H1N1 virus swept quickly around the world.

In 1947 a new variant of the H1N1 virus appeared on military bases – first noticed in Japan – and quickly spread from there. While it produced a generally mild illness there were apparently low levels of immunity in the population (see EID Journal Influenza Pandemics of the 20th Century). 1947 is little remembered today, except by epidemiologists, because while widespread, this new flu strain produced few excess deaths.

.

And then there were the epidemics that might have been – but that for reasons unknown – didn’t happen.

In early 1976, after an absence of nearly two decades, a never-before-seen strain of H1N1 swine flu appeared at Ft. Dix, New Jersey – prompting a national emergency response for its expected return in the fall. While that failed to happen (see Deja Flu, All Over Again), the following year we were blindsided by the `Russian’ H1N1 flu described above.

Why the 1976 H1N1 Swine flu fizzled out remains a mystery.

As we go into each year’s flu season, we are always presented with a `Forrest Gump’ moment. We never quite know what we are going to get.

But we do know that even in a non-pandemic year, we can see tens of thousands of American lives lost due to influenza. Globally, we are talking hundreds of thousands. And that a season can start off mild and unassuming (like 1950) and end up as a raging epidemic.

We also know that a flu season can affect different parts of the world differently. We may very well see an H3N2-centric flu season this year in North America, but in Europe or Asia, they could easily see H1N1 instead.

While every year is a question mark, this year we have a number of additional variables at play. The first comes from the rise in the number of antigenically diverse H3N2 clades being reported around the world (see ECDC: Influenza Characterization – Sept 2014).

Since this fall’s vaccine strains were selected last February, the `balance of power’ among flu H3N2 flu strains has begun to shift, and the H3N2 component for next year’s Southern Hemisphere flu shot has already been changed to meet the challenge of an emerging A/Switzerland/9715293/2013 (H3N2)-like virus.

Complicating matters, last week it was announced that last year’s LAIV (Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine) – aka FluMist nasal spray vaccine – was not effective against the H1N1(pdm) virus in children aged 2-8, and that it is likely to be ineffective this year as well.

And if all of this isn’t enough uncertainty, this year we are watching more novel flu strains than ever before; H7N9, H5N1, H5N6, H5N2, H5N8, H5N3, H9N2 and H10N8 just to mention the biggest concerns. You’ll find an excellent overview of these emerging avian flu threats in this weeks’ FAO-EMPRES Report On The Emergence And Threat Of H5N6.

As I’ve written here often , flu vaccines are considered very safe – and most years provide a moderate level of protection against influenza. While there are some questions regarding this year’s vaccine `match’ with circulating strains, some protection beats no protection any day of the week.

While the vaccine can’t promise 100% protection, it – along with practicing good flu hygiene (washing hands, covering coughs, & staying home if sick) – remains your best strategy for avoiding the flu (and other viruses) this winter.

Meanwhile, we have what is shaping up to be a fascinating year for studying all types of flu viruses.