P&I Mortality the past 5 Flu Seasons – Credit FluView

# 9987

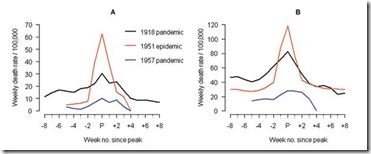

With this year’s flu season essentially over in the Northern Hemisphere, it is time once again for the CDC to assess the damage, and as many already know – it was a tough flu year. Between having an H3 dominated year, and a `drifted’ H3N2 virus that largely evaded this year’s vaccine, the impact was particularly hard on those over the age of 65.

2014-15 will go down as the third moderately severe flu season in a row, which followed two comparatively mild seasons (2010-11 & 2011-12), proving you just never know what the next flu season will bring.

Yesterday the CDC released the following post-mortem analysis of this latest influenza epidemic season.

2014-2015 Flu Season Drawing to a Close

April 27, 2015 – Flu activity continues to decline, according to the most recent FluView, which reports that influenza-like-illness (ILI) in the United States has fallen below baseline for the second consecutive week since the middle of November. Other key indicators are declining as well, signaling that the 2014-15 flu season is drawing to a close. The April 24, 2015 FluView covers influenza activity reported from April 12-April 18, 2015.During the 2014-2015 season, influenza activity started early and had a relatively long duration. Influenza-like-illness (ILI) went above baseline the week ending November 22 and remained elevated for 20 consecutive weeks, making this season slightly longer than average. For the past 13 seasons, influenza-like-illness has been at or above baseline for 13 weeks on average, with a range of 1 week to 19 weeks. The ILI curve for this season is most similar to that from the 2012-2013 season, which is the season during which ILI activity remained above baseline for 19 weeks.

This season was severe for people 65 and older especially. While hospitalization rates are almost always highest among people 65 and older, this season CDC recorded the highest hospitalization rates among this age group since this type of record-keeping began in 2005. People 65 and older accounted for more than 60 percent of all reported hospitalizations and from September 28 through April 18, an estimated 313.8 per 100,000 people in the age group were hospitalized from flu. The next highest recorded hospitalization rate in this age group (182.3 per 100,000) occurred during the 2012-2013 season.

The extremely high hospitalization rate in older adults elevated the overall hospitalization rate for all age groups in the United States to 63.6 per 100,000 people. Hospitalization rates for other age groups were either similar to or lower than what has been seen previously. For example, the age group normally next-most affected by severe illness resulting in hospitalization is children 0-4 years of age. While children in that age group did have the second-highest hospitalization rate this season, that rate through the week ending April 18 (55.4 per 100,000) is lower than what was seen during the same week in 2012-2013 (65.9 per 100,000).

During most of the season influenza A (H3N2) viruses predominated however the country experienced a second wave of influenza B flu activity since early March. Second waves of influenza B activity are common. Seasons during which influenza A (H3N2) viruses predominate typically have higher rates of hospitalizations and more deaths, particularly among older people and children. The last season when H3N2 viruses predominated was in 2012-2013.

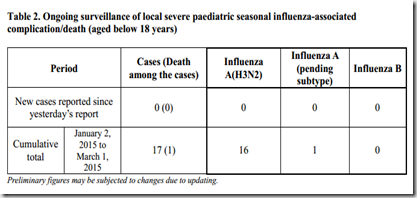

Flu-related deaths this season were within expected boundaries for an H3N2 dominant season. CDC monitors flu-related deaths through the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System, which reports the total number of death certificates processed and the number of those for which pneumonia or influenza is listed as the underlying or contributing cause of death in 122 U.S. cities. Pneumonia and influenza diagnoses (P&I) first rose above the epidemic threshold the week ending January 3, 2015 and peaked the week ending January 17, 2015 at 9.3%. This is comparable to recorded percentages for past severe seasons, including the 2003-04 season when P&I reached 10.4% and the 2012-13 flu season when P&I peaked at 9.9%.

Our eyes now turn to the Southern Hemisphere, where the newly formulated flu vaccine is hoped will make a bigger dent in H3N2’s impact this year. But we never really know whether the Southern Hemisphere will be a continuation of our outgoing flu season, or prove to be a harbinger of changes we might see here come the fall.