26 pounds of confiscated raw Quail Eggs – Credit U.S. Customs

# 9885

Every once in awhile we hear a story about someone attempting to bring potentially dangerous food items or even live animals into this, or other countries, packed in their luggage. Sometimes there are attempts to conceal these items, and other times they are declared only for their owners to discover they are prohibited, and must be destroyed.

A few examples over the years:

- In 2010, two men were indicted for attempting to smuggle dozens of song birds (strapped to their legs inside their pants) into LAX from Vietnam (see Man who smuggled live birds strapped to legs faces 20 years in prison).

- In 2012, in Taiwan Seizes H5N1 Infected Birds, we learned of a smuggler who was detained at Taoyuan international airport in Taiwan after arriving from Macau with dozens of infected birds. Nine people exposed to these birds were observed for 10 days, and luckily none showed signs of infection.

- In May of 2013, in All Too Frequent Flyers, we saw a Vietnamese passenger, on a flight into Dulles Airport, who was caught with 20 raw Chinese Silkie Chickens in his luggage.

- The following month we saw a traveler (see Vienna: 5 Smuggled Birds Now Reported Positive For H5N1) attempt to smuggle 60 live birds into Austria from Bali, only to have 39 die in transit, and five test positive for H5N1. Fortunately, no humans were infected.

Today, Boston’s WCBV-TV is reporting that customs officials at Logan Airport intercepted, and destroyed, 26 pounds of raw quail eggs being brought in by a passenger from Vietnam (who declared the food items).

Vietnam is one of those countries where H5N1, and other avian flu viruses have been been frequently reported, making raw eggs (and the material they are packed in) potentially hazardous.

Passenger at Logan found with 26 pounds of quail eggs

Customs agents destroy quail eggs

UPDATED 12:35 PM EDT Mar 30, 2015

BOSTON —A passenger carrying 26 pounds of raw quail eggs was intercepted at Logan Airport earlier this month, authorities said.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials said the passenger had just arrived from Vietnam and declared various foods to customs agents, including 26 pounds of quail eggs wrapped in rice hulls.

All eggs and egg products originating from countries or regions affected with avian flu must be accompanied by a USDA Veterinary Services permit and meet all permit requirements, or be consigned to an approved establishment, according to officials.

While we don’t hear about it often, every day customs officials intercept thousands of pounds of potentially hazardous food items, or exotic animals, that could easily be carrying a dangerous disease like avian flu.

Individually, most of these incidents represent a low risk of infection, but that risk is not zero. And that risk is multiplied by hundreds of incidents around the globe each day.

The movement of poultry and poultry products across porous borders in China, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, India, and Bangladesh has undoubtedly helped in the spread of the H5N1 virus.

And more than a dozen years ago `wild flavor’ restaurants were the rage in mainland China, but most particularly in Guangzhou Province. Diners there could indulge in exotic dishes – often slaughtered and cooked tableside - including dog, cat, civit, muskrat, ferret, monkey, along with a variety of snakes, reptiles, and birds.

It was from this practice that the SARS is suspected to have emerged, when kitchen workers apparently became infected while preparing wild animals for consumption.

From there 8,000 people were infected, 800 died, and the world brushed uncomfortably close to seeing the first pandemic of the 21st century.

Perhaps even more risky is the (often illegal) trade in exotic animals, such as birds and small mammals.

Photo Credit USDA

In November of 2011, in Psittacosis Identified In Hong Kong Respiratory Outbreak, we saw a limited outbreak among personnel at an agricultural station where smuggled birds seized by customs agents had been quarantined. Subsequently 3 parrots died, and 10 were euthanized.

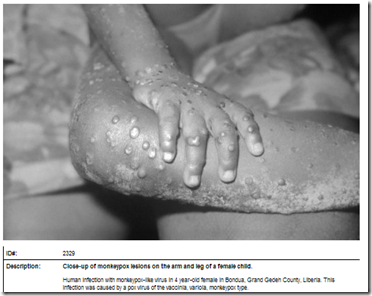

Another example, in 2003 we saw a rare outbreak of Monkeypox in the United States when an animal distributor imported hundreds of small animals from Ghana, which in turn infected prairie dogs that were subsequently sold to the public (see MMWR Update On Monkeypox 2003)

(Photo Credit CDC PHIL)

This outbreak infected at least 71 people across 6 states. Fortunately, no one died, as the virus has a relatively high (10%) fatality rate in Africa (see `Carrion’ Luggage & Other Ways To Import Exotic Diseases).

While the next pandemic virus is far more likely to arrive carried by an infected, but not yet symptomatic, air traveler – that isn’t the only plausible import scenario.

Beyond H5N1, SARS and monkeypox, a few other viruses of concern include Hendra, Nipah, Ebola, other avian influenzas (H7N9, H5N6, H5N8, etc.), assorted hemorrhagic fevers, many variations of SIV (Simian immunodeficiency virus), and of course . . . Virus X.

The one we don’t know about. Yet.