# 2489

Today we get a fascinating historical perspective of two millennium of pandemics and epidemics by three authors from the NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases).

In their 10 page report Emerging Infections: A Perpetual Challenge authors David Morens, GK Folkers and Anthony S. Fauci take us from the Plague of Athens (430 B.C.) to the 1918 Spanish Flu, with stops at the Black Death (1347-50), The French Pox (Syphilis) (1494), American Yellow Fever (1793-98), and the Fijian Measles Epidemic (1875) - among others.

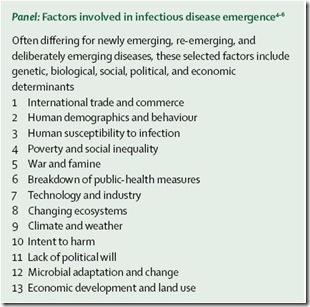

The authors cite 13 factors that, historically have contributed to the spread of epidemics and pandemics.

The 10 pandemics/epidemics described in this paper are not the only ones to occur over the last 2000 years, of course. They were chosen because they are reasonably well documented, and were "representative of a range and complexity of circumstances, stretching over more than two millennia".

This paper is a good read, not overly technical, and an excellent reminder that emerging infectious diseases are something we humans have dealt with for millennia, and that there is no sign of that changing anytime soon.

As the authors put it in their conclusion (reparagraphed for readability):

Well-understood determinants of modern disease emergence, typically acting in concert, have been associated throughout recorded history with the emergence of major diseases. These determinants have been similar in their explosiveness, impact, and elicitation of public-health control responses.

Whether the nature and pattern of these determinants are changing or will change in the future remains speculative. That most of the historical emerging diseases we examined were associated with unique patterns of common determinants suggests to us that an increasingly complex modern world will probably provide increasing opportunities for disease emergence.

For centuries a fundamental challenge to the existence and well-being of societies—as reflected by scientific attention, as well as in art, religion, and culture—emerging infections remain among the principal challenges to human survival.

Here is the NIH Press release on this paper.

Study of Ancient and Modern Plagues Finds Common Features

In 430 B.C., a new and deadly disease — its cause remains a mystery — swept into Athens. The walled Greek city-state was teeming with citizens, soldiers and refugees of the war then raging between Athens and Sparta. As streets filled with corpses, social order broke down. Over the next three years, the illness returned twice and Athens lost a third of its population. It lost the war too. The Plague of Athens marked the beginning of the end of the Golden Age of Greece.

The Plague of Athens is one of 10 historically notable outbreaks described in an article in The Lancet Infectious Diseases by authors from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health. The phenomenon of widespread, socially disruptive disease outbreaks has a long history prior to HIV/AIDS, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), H5N1 avian influenza and other emerging diseases of the modern era, note the authors.

"There appear to be common determinants of disease emergence that transcend time, place and human progress," says NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., one of the study authors. For example, international trade and troop movement during wartime played a role in both the emergence of the Plague of Athens as well as in the spread of influenza during the pandemic of 1918-19. Other factors underlying many instances of emergent diseases are poverty, lack of political will, and changes in climate, ecosystems and land use, the authors contend. "A better understanding of these determinants is essential for our preparedness for the next emerging or re-emerging disease that will inevitably confront us," says Dr. Fauci.

"The art of predicting disease emergence is not well developed," says David Morens, M.D., another NIAID author. "We know, however, that the mixture of determinants is becoming ever more complex, and out of this increased complexity comes increased opportunity for diseases to reach epidemic proportions quickly."

For example, more people travel more often over greater distances and in less time now than at any time in the past. One consequence of the increased mobility in the modern age can be seen in the 2003 outbreak of the novel illness SARS, which rapidly spread from Hong Kong to Toronto and elsewhere as infected passengers traveled by air.

To better understand and predict disease emergence, Dr. Morens and his coauthors stress the need for research aimed at broadly understanding infectious diseases as well as specifically understanding how disease-causing microorganisms make the jump from animals to humans.

Reference:

DM Morens, GK Folkers and AS Fauci. Emerging infections: A perpetual challenge. The Lancet Infectious Diseases DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70256-1 (2008).

Note:

The complete paper is available HERE: