# 3374

Like it or not, the H1N1 swine flu virus is likely to be a fixture of our lives for the next several years.

That isn’t to say there aren’t scenarios where this virus could disappear (or possibly be replaced by something else), but the most likely scenario is that this H1N1 virus either co-circulates with the existing seasonal flu viruses or it pushes them aside to become king of the viral mountain.

Exactly what will happen is unknown. Influenza viruses are unpredictable, and as history tells us, pandemics come in all shapes and sizes.

While our experience with pandemics is limited, we do have 4 events to draw from over the past 120 years. Admittedly, there is much we don’t know about the science of the two earliest events, but we do have some interesting data about their impacts.

As a caveat to the data I’m about to present, a pandemic isn’t a monolithic event. What happens in one part of the world may be a far cry from what happens someplace else.

The graphs below are snapshots of events from specific locations. The tell part of the story, but they don’t tell the entire story.

We’ve four very interesting graphics from The Signature Features of Influenza Pandemics — Implications for Policy (Mark A. Miller, M.D., Cecile Viboud, Ph.D., Marta Balinska, Ph.D., and Lone Simonsen, Ph.D.) published by the New England Journal of Medicine.

Mortality Distributions and Timing of Waves of Previous Influenza Pandemics.

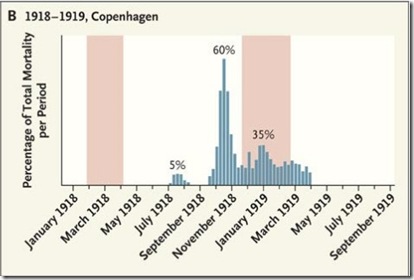

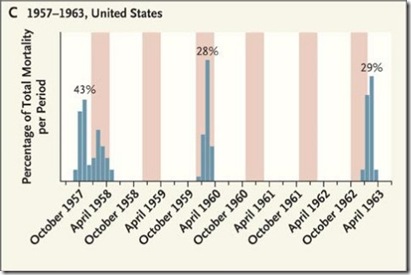

Proportion of the total influenza-associated mortality burden in each wave for each of four previous pandemics is shown above the blue bars. Mortality waves indicate the timing of the deaths during each pandemic. The 1918 pandemic (Panel B) had a mild first wave during the summer, followed by two severe waves the following winter. The 1957 pandemic (Panel C) had three winter waves during the first 5 years. The 1968 pandemic (Panel D) had a mild first wave in Britain, followed by a severe second wave the following winter. The shaded columns indicate normal seasonal patterns of influenza.

I’ve reproduced each graphic below. The comments beneath each are mine.

The pandemic of 1889-1892 is the earliest influenza pan-event that we have relatively good data on. As you can see, the pandemic hit hardest in the second and third waves, with wave #2 not hitting until about 14 months after the first wave began.

The causative agent for this pandemic is believed by some to have been the H2N2 virus (which sparked the 1957 event), but proof of this theory is lacking.

This pandemic is thought to have killed as many as 1 million people (at a time when the world’s population was about 1.5 billion), but of course record keeping in much of the world was haphazard at best.

The granddaddy of all pandemics was the 1918 Spanish flu, and this graph shows the experience of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Once again we see a mild `herald’ wave, followed just a few months later by a much stronger second wave.

The experience of northern Europe during the 1918 pandemic was quite different than some other parts of the world. The CFR (Case Fatality Ratio) was lower than many other parts of the world.

Another view (below) comes from the United States, and shows the 1918-1919 spike quite clearly. This from:

REVIEW AND STUDY OF ILLNESS AND MEDICAL CARE WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO LONG-TIME TRENDS

Public Health Monograph No. 48, 1957 (Public Health Service Publication No. 544)

But we find something very curious when we look at this next graph, which shows the influenza excess mortality (albeit on a different scale than the above graph) for the decade of the 1920s.

The years 1923, 1925, and 1929 all saw increased P&I (pneumonia & Influenza) mortality rates well above normal. While the pandemic was `officially’ over in 1919, the virus obviously continued to deliver a serious punch off and on for the next ten years.

The total number of deaths from the Spanish flu are unknown, but estimates run anywhere from 40 million to as high as 100 million people.

It would be nearly another 40 years before another pandemic would strike the world, although we had two close calls in the interim.

First, what many would term a pseudo-pandemic in 1947 produced widespread illness, but was very mild and resulted in few deaths and second, the killer Liverpool Flu of 1951 (see Sometimes . . . Out Of The Blue) which died out for reasons unknown after just six weeks.

In 1957, however, the H2N2 virus usurped the H1N1 virus’s hold on the world, and produced a pandemic that is blamed for the deaths of between 1 and 4 million people.

At the time, the world’s population was less than half of what it is today, and so a pandemic of similar severity might kill as many as 10 million people today.

Once again, there were significant pandemic waves in alternating years up until the 1962-63 flu season. The 1957 pandemic period could legitimately be described as having lasted five years.

The last pandemic was 41 years ago, and as this graph shows, in England and Wales it began in 1968 as a very mild illness, returning a year later with a much bigger impact.

Although the H3N2 virus which sparked the 1968 pandemic (which killed as many as 1 million people worldwide) would become the dominant seasonal flu strain, replacing the 1957 H2N2 virus, this was the shortest of the four pandemics – lasting only about 15 months.

As difficult as it is determining when a pandemic starts, it is often easier than figuring out when one ends.

The last four pandemics had durations of anywhere from just over a year (1968) to five years (1957). And in each case, no one knew that the pandemic was over until a year or more had passed since the last serious wave of illness.

We may get lucky, and see a 1968 style event (or luckier still, and have this turn out like 1947). This novel H1N1 virus may remain relatively mild, and after delivery a nasty flu season, simply become part of the seasonal mix.

The problem is, you don’t know until its over, how bad any pandemic is going to be. The second or third (or potentially even a 4th or 5th) wave could come along with entirely new characteristics.

It could be milder, or it could be more severe.

And the `pandemic experience’ in one part of the world may be vastly different than it is in another.

All of this points out the need for nations, businesses, and individuals to be taking the `long view’ with regards to the H1N1 virus.

We need to be thinking in terms of how we will deal with this pandemic potentially over a period of years, not just weeks or months.

If you haven’t visited the HHS’s pandemicflu.gov planning and information site, now is the time to do so. There you will find good information on how to prepare your workplace, or your home for a pandemic.

While this virus may appear relatively mild right now, that could change.

It is only prudent to take this threat seriously.

If you are prepared for a pandemic, then you are probably in pretty good shape to weather any disaster.

Since a pandemic, or an earthquake, or a flood, or a tornado can occur at just about anytime, with little or no advance warning, it just makes sense to get prepared, and to stay prepared.

Some links to get you started include:

FEMA http://www.fema.gov/index.shtm

READY.GOV http://www.ready.gov/

AMERICAN RED CROSS http://www.redcross.org/

For Pandemic Preparedness Information:

For more in-depth emergency preparedness information I can think of no better resource than GetPandemicReady.Org. Admittedly, as a minor contributor to that site, I'm a little biased.