# 5053

When it comes to governmental funding, public health is far too often the last to see new appropriations and the first to see budget cuts when times are lean.

Unless there is some ongoing high-profile health crisis (like a pandemic), those who work in public health toil outside of the limelight, focusing on the vital but unglamorous task of preventing disease outbreaks.

It is an old adage, but nonetheless true.

When public health works, nothing happens.

No so long ago, it appeared as if the age of infectious diseases – at least in developed countries – would soon be at an end.

Between vaccines, water treatment plants, and sophisticated sewage treatment and sanitation infrastructures, public health initiatives have eliminated many of the major infectious disease threats from our communities.

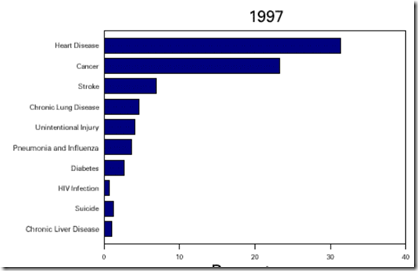

In 1900, the top three causes of death in the United States were from infectious diseases; Pneumonia, TB, and Diarrhea & Enteritis (usually food/water borne).

Skip ahead to 1997, and only Pneumonia remains in the top 10 list (rate cut by 2/3rds, down to #6).

(From MMWR Achievements in Public Health, 1900-1999: Control of Infectious Diseases)

But now – with increasing globalization and travel – many developed countries are facing the encroachment and/or introduction of exotic, newly emerging or rarely seen pathogens.

Dengue, HIV, Chikungunya, Ebola, Lassa Fever, Rift Valley Fever, CCHF, Hendra, Nipah, SARS . . . the list is long, and growing.

To combat these invaders, here in the United States, we’ve got the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) branch of the CDC, which since 1951 has provided epidemiologic assistance to local health departments within the United States and to countries throughout the world.

Maryn McKenna’s first book, Beating Back The Devil (2004) takes us behind the scenes with these disease detectives as they investigate outbreaks all over the world. Highly recommended.

For the past 20 years Australia has had their own disease detectives - from the Master of Applied Epidemiology (MAE) program which has been run out of the Australian National University.

Over the past 2 decades, students and teachers from ANU have investigated – and worked to quell – more than 200 disease outbreaks including SARS, Hendra Virus, and novel H1N1.

Now, according to reports by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC News), their funding is about to be eliminated, and this program is in danger of shutting down.

Epidemic research program runs out of funds

A university program which helped Australia's respond to major disease outbreak will be disbanded at the end of next year.

The Federal Government has cut funding to the Australian National University's Master of Applied Epidemiology (MAE) program.

A sign of these tough economic times, no doubt. And certainly not the only cut that public health programs around the world are enduring right now.

But this funding cut is particularly disturbing because Australia is geographically positioned to respond quickly to - and serve as an early warning system for - emerging disease threats coming out of Asia or any of the western Pacific rim nations.

Areas of the world that have a history of producing emerging pathogens (H5N1, SARS, NDM-1, Nipah, Hendra, H3N2, H2N2, etc.).

So the cutting of the MAE program would not only leave Australia more vulnerable to disease outbreaks, it has the potential to negatively impact all of us around the world.

Hopefully some source of additional funding will be found before this program is disbanded.

But the bigger problem persists.

No longer can we depend upon vast oceans, or lengthy travel times, to protect us against disease outbreaks in remote regions of the earth.

An emerging epidemic problem anywhere in the world has the potential to become a problem to the rest of the world – in a matter of days or even hours.

Which is why we need to be increasing our funding of public health initiatives . . . not decreasing them.

When it comes to funding public health, we can either pay now . . . or we will surely pay later.