Photo Credit CDC Influenza Home Care Guide

Keypoints

- New study found H1N1pdm virus among a small minority of samples tested during the opening weeks of the 2009 Pandemic in New South Wales

# 8762

During the opening days, weeks and months of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, just about anyone who came down with an influenza-like Illness (ILI) was convinced they had contracted the dreaded `swine flu’. It was, after all, featured on just about every newscast, some governments were handing out antivirals based on symptoms alone, and there were daily dire warnings about its global spread.

But during the pandemic, just as we see during every flu season, influenza isn’t the only respiratory virus in circulation. That terrible `flu’ you think you had last year?

Well, it may have been something else, entirely.

During the fall of 2009, at the height of the H1N1 pandemic in the United States, I highlighted the following CDC graphic in a blog called ILI’s Aren’t Always The Flu, that showed that 70% of the samples taken from symptomatic patients tested negative for influenza.

While we tend to think of influenza as the `severe’ respiratory virus, and all of the others as milder, that isn’t always the case. Again, during the fall of 2009, we saw reports indicating that a large number of `non-influenza’ severe respiratory infections were treated at Philadelphia’s Children’s Hospital.

Thu, Nov. 12, 2009

Tests show fall outbreak is rhinovirus, not swine flu

By Don Sapatkin

Inquirer Staff Writer

(EXCERPT)

Tests at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia suggest that large numbers of people who got sick this fall actually fell victim to a sudden, unusually severe - and continuing - outbreak of rhinovirus, better known as a key cause of the common cold.

Experts say it is logistically and financially impossible to test everyone with flulike symptoms. And signs, treatment, and prognoses for a bad cold and a mild flu are virtually identical, so the response hardly differs.

And the same is true every flu season. Common respiratory viruses include metapneumovirus, parainfluenzavirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), adenovirus, or most likely, one of the myriad Rhinoviruses (Common cold).

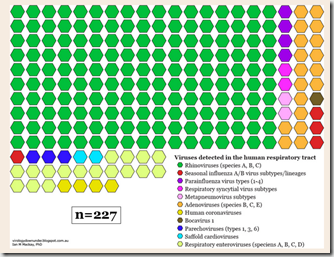

Something that Dr. Ian Mackay has addressed well, and often, in the past. The following chart comes from his recent blogs on the topic; Respiratory viruses: the viruses we detect in the human respiratory tract:

All of which serves as prelude to a new study, conducted in New South Wales, that examines 255 respiratory samples taken during the opening months of the 2009 pandemic, to try to examine exactly what viruses were present. The results, as you have probably already ascertained, were heavily weighted towards `non-influenza’ viruses.

Vigneswary Mala Ratnamohan, Janette Taylor, Frank Zeng, Kenneth McPhie, Christopher C Blyth, Sheena Adamson, Jen Kok and Dominic E Dwyer

Virology Journal 2014, 11:113 doi:10.1186/1743-422X-11-113

Published: 18 June 2014

Abstract (provisional)

Background

During the early phases of the 2009 pandemic, subjects with influenza-like illness only had laboratory testing specific for the new A(H1N1)pdm09 virus.

Findings: Between 25th May and 7th June 2009, during the pandemic CONTAIN phase, A(H1N1)pdm09 virus was detected using nucleic acid tests in only 56 of 1466 (3.8%) samples meeting the clinical case definition required for A(H1N1)pdm09 testing. Two hundred and fifty-five randomly selected A(H1N1)pdm09 virus-negative samples were tested for other respiratory viruses using a real-time multiplex PCR assay. Of the 255 samples tested, 113 (44.3%) had other respiratory viruses detected: rhinoviruses 63.7%, seasonal influenza A 17.6%, respiratory syncytial virus 7.9%, human metapneumovirus 5.3%, parainfluenzaviruses 4.4%, influenza B virus 4.4%, and enteroviruses 0.8%. Viral co-infections were present in 4.3% of samples.

Conclusions

In the very early stages of a new pandemic, limiting testing to only the novel virus will miss other clinically important co-circulating respiratory pathogens.

The entire study is available as a PDF at this link. I’ve excerpted the last two paragraphs from the study below:

Even prior to the widespread transmission of A(H1N1)pdm09 virus in Australia, limiting testing to travellers did not improve the specificity of testing. Furthermore, if laboratories use NAT to determine other causes of infection, testing capacity in an outbreak may soon be reached. However, when the causative pathogen of an outbreak has been identified and the outbreak has progressed beyond containment, then the testing algorithms need revision to target only specific indications, such as a location of new or significant clusters, or for individuals at risk of severe disease.

In conclusion, laboratory testing specifically targeting only the new virus will miss other clinically important co-circulating respiratory pathogens in the very early stages of a pandemic. Detecting the presence of other viruses may provide important information on the impact of pre-existing viruses when a new pandemic virus is circulating.

It should be noted that the 2009 H1N1 pandemic began when the northern hemisphere’s flu season was coming to an end, and the southern hemisphere’s flu season was just getting started.

One can’t automatically assume that the same sorts of ratios would have prevailed in regions where other viruses were circulating less frequently. Interestingly, the rate of H1N1pdm positive tests may very well have been dampened in the Southern Hemisphere by the co-circulation of some of these other viruses.

A topic that Ian Mackay explored earlier this week in Influenza in Queensland, Australia: 1-Jan (Week 1) to 8-June (Week 23); the idea that the body’s immune response to one viral infection may temporarily protect you against infection from another.

And an idea similar to one we looked at back in 2010 in Eurosurveillance: The Temporary Immunity Hypothesis (and again, in 2012 in EID Journal: Revisiting The `Canadian Problem’.