MERS Cases By Month – Credit Maia Majumder Mens Et Manus

# 8693

While the number of MERS cases being reported on a daily basis has dropped markedly since the end of April, May was still the second most active month (by a long shot), running more than 10 times the average of all of the months prior to April 2014.

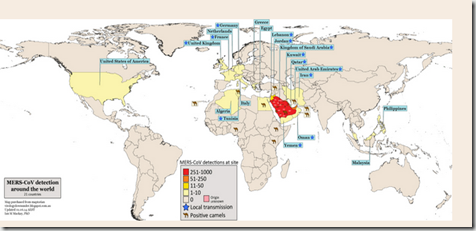

And along with this continued growth in the number of cases, we’ve also see a geographical expansion, with imported cases reported for the first time in The United States, Lebanon, The Netherlands, Iran, and yesterday . . . Algeria.

Credit Dr. Ian Mackay VDU Blog 21 Countries and Counting . . .

Simply put, had we not seen 300 cases reported in April, we’d scarcely be comforted by seeing `only’ 150 cases in May.

The recent dramatic drop in cases reported by Saudi Arabia is most likely due to better infection control and containment in hospital settings, but that leaves us with a big unknown when it comes to community transmission.

A question that looms even larger now that we’ve seen recent exported cases among Umrah pilgrims returning home to the Netherlands, Iran and Algeria.

While the Netherlands case may have acquired the virus while visiting a hospital (see Eurosurveillance Report), we have scant knowledge of how these other cases became infected. Likewise, we continue to see reports from Saudi Arabia of what appear to be community acquired cases.

Given the spectrum of illness we’ve seen with the MERS coronavirus – ranging roughly 50% being severe or life threatening to roughly 20% being asymptomatic - it is reasonable to assume that some cases are going undetected in the community.

Whether that number is large or small is a matter of some debate.

Last November, we looked at a study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, that attempted to quantify the likely extent of transmission of the MERS virus in the Middle East. (Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: quantification of the extent of the epidemic, surveillance biases, and transmissibility).

- They calculated that for every case identified, there are likely 5 to 10 that go undetected – and suggested that this virus may be transmitting more efficiently than previously estimated.

Last month, in The Elusive R0 of MERS, we looked at another study (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Corona virus, MERS-CoV. Conclusions from the 2nd Scientific Advisory Board Meeting of the WHO Collaborating Center for Mass Gathering Medicine, Riyadh.) that concluded the virus was transmitting far less efficiently and stated that:

- The basic reproductive rate of the virus (R0) is definitely below 1 and probably below 0.5 clearly showing that the virus has no pandemic or even local epidemic potential

Not exactly a consensus of opinion.

At this point, all we can really say is we’ve not seen the kind of exponential growth in severe MERS cases that we would expect to see if MERS-CoV were transmitting efficiently in the community. However, MERS surveillance outside of the hospital environment in Saudi Arabia is spotty at best.

While the number of known cases exported from Saudi Arabia remains relatively low, we’ve added four new countries to the list in just the past couple of weeks (Netherlands, Lebanon, Iran & Algeria). Upping the ante will be several million religious pilgrims who will travel to Saudi Arabia (for Ramadan & the Hajj) over this summer and fall.

Providing ample opportunities for additional international spread of the virus, something the CDC has already stated they would not be surprised to see.

As I wrote ten days ago in Dealing With A Lighter Shade Of MERS, this virus needn’t acquire enhanced transmissibility and start to sweep madly across the landscape to become a serious public health issue.

It already is one.

Every infected traveler detected – even if we are talking a relatively small number – sets into motion a very expensive and oft times disruptive public health response.

Hundreds of fellow travelers or close contacts may have been exposed, scores of exposed healthcare workers may have to be furloughed to home isolation, and extensive contact tracing & testing programs will have to be initiated.

And this impact extends beyond the few infected arrivals that may show up at the gate – as anyone symptomatic and with a travel history to the Arabian peninsula must be isolated, tested, and their infection ruled out.

If that doesn’t sound like a big deal, consider these opening lines from a Clinical Infectious Diseases study - Unmasking Masks in Makkah: Preventing Influenza at Hajj – from 2012.

Each year more than 2 million people from all over the world attend the Hajj pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia. At least 60% of them develop respiratory symptoms there or during outward or homebound transit [1, 2] During recent interpandemic years, approximately 1 in 10 pilgrims with respiratory symptoms in Makkah have had influenza detected by polymerase chain reaction tests of respiratory samples [3, 4]. Pneumonia is the leading cause of hospitalization at Hajj, accounting for approximately 20% of diagnoses on admission [5].

While the vast majority of these respiratory infections will no doubt be due to rhinoviruses or influenza, figuring out which ones might be due to the MERS coronavirus will be a pretty tall order. And a challenge that must be faced by scores of countries - some far less equipped to do so than others – with returning pilgrims from all around the globe.

My crystal ball is foggy, so I can’t tell you whether MERS will blossom into a full-fledged pandemic, continue to creep along as it has, or if we’ll be eyeballing some completely different emerging disease threat six months from now.

We might even get lucky and MERS may recede back into the woodwork over the summer, although as long as it circulates in camels that seems unlikely.

But the truth is, even if MERS fizzles, all of this fuss and bother over this coronavirus won’t have been for naught.

Figuring out how to effectively respond to this novel respiratory virus now will provide us with the knowledge, experience, and infrastructure we’ll need to deal with the next pathogen that comes down the pike.

One that might not prove quite as easy to deal with as has MERS (Well, so far, anyway. . . ).