How viruses shuffle their genes (reassort)

# 9833

When it comes to the source for the next novel flu virus, nature has a lot of options.

Last month, in Virology J: Human-like H3N2 Influenza Viruses In Dogs - Guangxi, China, we looked at canine hosted flu viruses and their potential threat to humans, while last year in Keeping Our Eyes On The Prize Pig we looked at the array of swine variant flu viruses (H1N1v, H1N2v, H3N2v) that have sporadically jumped to humans over the past few years.

In Eurosurveillance: Avian H10N7 Influenza In Harbor Seals and mBio: A Mammalian Adapted H3N8 In Seals, we even looked at the potential for seeing a human flu arise from a marine mammal host.

Cats and bats and horses . . . even camels (see Equine H3N8 In Mongolian Bactrian Camel) . . . are susceptible to various types of flu viruses – a testament to influenza’s promiscuity and adaptability – and while pretty far down our suspect list, all probably have some possibility of spawning the next novel flu.

But influenza is first and foremost of avian origin, and has its greatest diversity and incidence in birds - both wild and domesticated – putting them at the top of our watch list.

Over the past several years we’ve watched an explosion in the diversity of highly pathogenic avian flu viruses around the world. While some of this shift may be due to better testing, surveillance, and reporting - there seems little doubt that we are seeing a increase in the incidence, variety, and virulence of avian flu viruses.

Of the avian flu viruses we are currently watching with the greatest concern – H5N1, H5N2, H5N3, H5N6, H5N8, H7N9, H10N8 - all share several important features (see Study: Sequence & Phylogenetic Analysis Of Emerging H9N2 influenza Viruses In China):

- They all first appeared in Mainland China

- They all have come about through viral reassortment in poultry

- And most telling of all, while their HA and NA genes differ - they all carry the internal genes from the avian H9N2 virus

Today we’ve a study, appearing in the Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases, that looks at the incidence of avian flu in live bird markets (LBMs) in Nanchang, China in late 2013 and early 2014, immediately following the first human H10N8 case reported in that city (see EID Dispatch: Human Infection with Influenza Virus A(H10N8) From LPMs).

.

Although hampered by a lack of sequencing, and limited to HA testing, this study turned up high levels of infection by H9, H10, and H5 viruses – with a surprisingly high rate of multiple flu infections among poultry.

First the link, abstract, and some excerpts – after which I’ll return with a bit more:

Maohong Hu1), Xiaodan Li2), Xiansheng Ni1), Jingwen Wu1), Rongbao Gao2), Wen Xia1), Dayan Wang2), Fenglan He1), Shengen Chen1), Yangqing Liu1), Shuangli Guo1), Hui Li1), Yuelong Shu2), Jeffrey W. Bethel3), Mingbin Liu1), Justin B. Moore4), Haiying Chen1)

[Advance Publication] Released 2015/03/13

Human infections with the novel H10N8 virus have raised concerns about pandemic potential worldwide. We report the results of a cross sectional study on avian influenza virus (AIV) in live poultry markets (LPMs) in Nanchang, China after the first patient case with H10N8 virus was reported in the city. A total of 201 specimens tested positive for AIVs of the 618 samples collected from 24 LPMs in Nanchang from December 2013 to January 2014.

We found that the LPMs were heavily contaminated by AIVs, with H9, H10 and H5 being the predominant subtypes and more than half of the LPMs providing samples positive for H10 subtype. Moreover, the coexistence of different subtypes was common in LPMs. Of the 201 positive samples, 20.9% (42/201) were mixed infections of different HA subtypes of AIVs.

Of the 42 mixed infections, 50% (21/42) were coexistence of H9 and H10 subtypes with or without H5, and were from chicken samples. This indicated that H10N8 virus probably originated from the segment reassortment of H9 and H10 subtypes during the period of emerging of the H10N8 virus.

The entire study is available online. One striking aspect is the shift in the subtypes of viruses detected over what was reported in the same region a decade ago. This from the study:

A previous study conducted in Nanchang approximately 10 years ago showed that H2, H3, H4 and H9 subtypes, were isolated most frequently from chickens and ducks in LPMs, but no H7 or H10 subtype was isolated (13). The difference of the subtypes revealed the variation of AIVs over time while H9 was continuous existing in the LPMs in Nanchang

Two years ago – coincidentally, just two weeks before we learned of the emergence of H7N9 in Eastern China – we looked at a study in the EID Journal: Predicting Hotspots for Influenza Virus Reassortment that found Eastern China to be one of the worlds best breeding grounds for novel flu viruses.

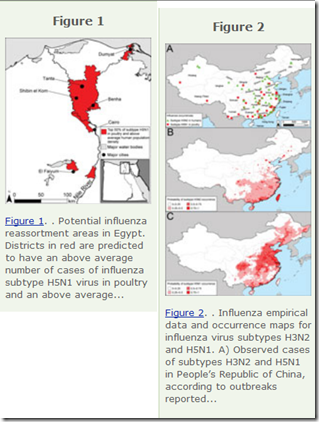

Potential geographic foci of reassortment include the northern plains of India, coastal and central provinces of China, the western Korean Peninsula and southwestern Japan in Asia, and the Nile Delta in Egypt.

Interestingly, two of the biggest concerns cited – China and Egypt – are the prime focus of our current bird flu watches, and H5N8 first came to our attention on the western Korean Peninsula just over a year ago.

While it is true that most of this new crop of avian influenza viruses have yet to demonstrate the ability to infect and sicken humans, their growing diversity provides essential viral building blocks from which new, possibility more dangerous, viruses can be constructed.

You can view a short (3 minute) video from NIAID on reassortment here.

And even viral subtypes that currently don’t easily infect humans can, over time, acquire genetic changes that might eventually change their behavior – either through further reassortment or antigenic drift. It is this continual evolutionary process - highlighted by the Journal Nature last week (see Nature: Dissemination, Divergence & Establishment of H7N9 In China) – that places H7N9 at or near the top of our pandemic threats list.

While we can’t predict when, from where, or through what HA-NA subtype the next pandemic will arise, what is clear is that we live in an increasingly viral-threat-rich environment, with new flu subtypes emerging over the past couple of years at an accelerated rate.

Which no doubt influenced the World Health Organization last month when they issued a statement called Warning signals from the volatile world of influenza viruses where they cautioned:

Indeed.