# 10,366

Up until a little over a decade ago, dogs were generally thought to be immune to influenza virus infection. In 2004, however, the equine H3N8 flu virus mutated enough to adapt to a canine host, and began to spread among greyhounds in Florida (see EID Journal article Influenza A Virus (H3N8) in Dogs with Respiratory Disease, Florida).

Since then canine H3N8 has been sporadically reported across much of the United States. It is considered a `canine specific’ virus, and there have been no reports of human infection.

But we’ve also seen evidence that other influenza viruses – including human and avian varieties – can infect canines.

- In 2008, CDC’s EID Journal carried a report on a newly emerging canine flu jumping from an avian source in Korea (see Transmission of Avian Influenza Virus (H3N2) to Dogs).

- During the 2009 pandemic we saw reports of dogs infected the H1N1 virus, and in the middle of the last decade we saw several reports indicating that dogs were susceptible to the H5N1 bird flu virus (see Study: Dogs And H5N1).

- More recently Korea reported H5N8 Antibodies Detected In South Korean Dogs (Again).

- And the Korean H3N2 virus which emerged in 2008 finally showed up in the United States a few months ago (see CDC’s Key Facts On The New H3N2 Canine Flu).

As often happens, the more we look, the more we find. The expanding host range for influenza viruses (which now includes humans, equines, swine, birds, bats, camels, guinea pigs, and a variety of land and marine mammals) and the genetic diversity of influenza viruses (currently with 8 hemagglutinin & 11 neuraminidase subtypes identified), continues to surprise.

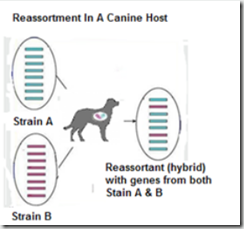

Last summer, in Study: Dogs As Potential `Mixing Vessels’ For Influenza - we looked at the ability of different influenza strains (canine, equine and human) to infect, and replicate in, canine tracheal tissues. And last February, in Virology J: Human-like H3N2 Influenza Viruses In Dogs - Guangxi, China, we looked at the discovery two H3N2 CIVs possessing high homology with human/swine influenza viruses.

While novel influenza infections among Mongolian Bactrian Camels and Peruvian guinea pigs pose fairly limited exposure risks to human populations, infection of companion animals like dogs and cats are another matter entirely.

Something that the American Society for Microbiology warned about last summer, in a press release on a study of canine influenza viruses:

Evolution of Equine Influenza Led to Canine Offshoot Which Could Mix With Human Influenza

CONTACT: Jim Sliwa

jsliwa@asmusa.org

WASHINGTON, DC – June 19, 2014 – Equine influenza viruses from the early 2000s can easily infect the respiratory tracts of dogs, while those from the 1960s are only barely able to, according to research published ahead of print in the Journal of Virology. The research also suggests that canine and human influenza viruses can mix, and generate new influenza viruses.

In this same vein, today we have a report - published in the EID Journal - detailing the discovery and isolation of Avian H6N1 in dogs in Taiwan.

H6N1 has been around for decades in Chinese poultry - it possesses similar internal genes to H5N1 and H9N2 (cite 2002 J Virol Molecular evolution of H6 influenza viruses from poultry in Southeastern China by Webster, Webby, Shortridge et al.) - and it has been speculated that it may have even been involved in the genesis of H5N1 in Hong Kong in 1997.

While viewed as having some pandemic potential in the 1990s, once H5N1 emerged as a serious threat in 2003, H6N1’s threat receded back into the shadows. When Taiwan’s CDC Reported the first Human Infection With Avian H6N1 two years ago, however, interest in H6N1 quickly rose.

- Last May,in the EID Journal: Seropositivity For H6 Influenza Viruses In China, researchers reported a low - but significant - level of antibodies, particularly among live bird handlers, to the avian H6 virus in China.

- And also last May, in Study: Adaptation Of H6N1 From Avian To Human Receptor-Binding, we saw a report citing changes the authors suggest are slowly moving the H6N1 virus towards preferential binding to human receptor cells instead of avian receptor cells

All of which makes H6N1 a virus of interest, and serves as prelude to today’s EID Journal article, which finds evidence of H6N1 infection in a small number of dogs sampled in Taiwan.

Influenza A(H6N1) Virus in Dogs, Taiwan

Hui-Ting Lin1, Ching-Ho Wang1, Ling-Ling Chueh, Bi-Ling Su, and Lih-Chiann Wang

Author affiliations: National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

Abstract

We determined the prevalence of influenza A virus in dogs in Taiwan and isolated A/canine/Taiwan/E01/2014. Molecular analysis indicated that this isolate was closely related to influenza A(H6N1) viruses circulating in Taiwan and harbored the E627K substitution in the polymerase basic 2 protein, which indicated its ability to replicate in mammalian species.

Infections with influenza viruses are rare in dogs. However, interspecies transmission of an equine influenza A(H3N8) virus to dogs was identified during a respiratory disease outbreak in Florida, USA, in 2004 (1). Influenza A(H6N1) virus is the most common naturally occurring avian influenza virus in Taiwan (2). Therefore, to determine to the prevalence of influenza A virus infection in dogs in Taiwan, we performed serologic analysis, 1-step reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) screening, and virus isolation.

The Study

A total 474 serum specimens were collected in Taiwan during October 2012–October 2013. Two hundred eighty-one specimens were collected from household (owned) dogs at the National Taiwan University Veterinary Hospital in Taipei. The remaining 193 serum specimens were obtained from free-roaming dogs in rural areas.

All serum specimens were tested for antibodies against influenza A virus by using a species-independent blocking ELISA (Influenza A Virus Antibody Test Kit; Idexx, Westbrook, ME, USA). All antibody-positive serum specimens were further tested by using a hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay. HI was determined according to procedures recommended by the World Organisation for Animal Health. Chicken erythrocytes (1%) were used. Serum samples were treated with receptor-destroying enzyme (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan) before conducting the assay to destroy nonspecific inhibitors (3). A/chicken/Taiwan/2838V/2000 (H6N1) and A/chicken/Taiwan/1209/03 (H5N2) viruses were used as antigens.

(SNIP)

Conclusions

Avian influenza A(H6N1) viruses have been widespread in chickens in Taiwan since 1972 (13–15). These viruses are clustered in a unique lineage that differs from viruses circulating in Hong Kong and southeastern China since 1997 (13). Unlike avian species, H6 subtype virus infections are rare in mammals.

In this study, 9 of 474 dog serum specimens were positive for influenza A virus by ELISA, and 4/185 (2.1%) dogs had RT-PCR−positive results for this virus. A/canine/Taiwan/E01/2014 was isolated from 1 dog that was co-infected with canine distemper virus. On the basis of molecular analysis of A/canine/Taiwan/E01/2014, HA, NA, PB1, PB2, NP, and NS genes showed high homology (>97% nucleotide identity) with avian H6N1 subtype virus isolates that are currently prevalent in Taiwan. PA and M genes of A/canine/Taiwan/E01/2014 showed 99% nucleotide identity with A/chicken/Taiwan/2593/2013 (H5N2).

Phylogenetic analysis showed that 8 eight virus genes were derived from H6N1 subtype viruses isolated in Taiwan. All 8 influenza virus genes found in the dog probably originated from avian sources. We speculate that a complete avian influenza virus had infected this dog. However, additional analysis is required to verify this hypothesis.