#18,786

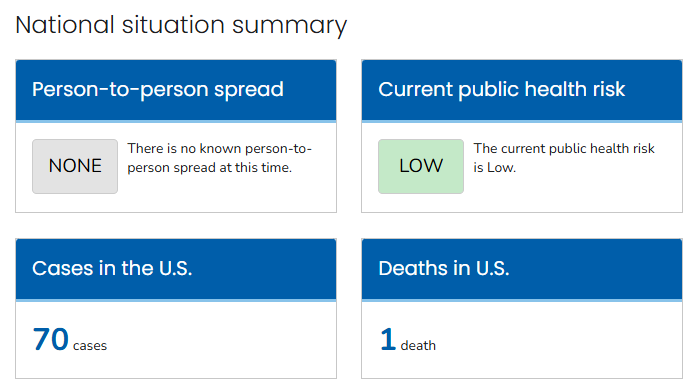

It has been widely reported overnight that the CDC has ended their Emergency Response to H5N1 Avian flu, but the only overt sign I've found thus far on the CDC website is the above statement indicating that updates to their H5 Bird Flu: Current Situation webpage will now be made monthly.

Admittedly, the number of human cases in the United States has remained stable since February (although some cases may have been missed). If an agency felt the need to temporarily stand down - I can see why this recent respite would seem the ideal time to do so.

That said, last fall in MMWR: Serologic Evidence of Recent Infection with HPAI A(H5) Virus Among Dairy Workers, we learned that some percentage (7% in the study) of dairy workers have likely been infected asymptomatically.

The USDA's Dairy Herd Status Program website was last updated in late June, and still shows only 111 herds (out of an est. 36,000) from 20 states enrolled in the voluntary herd monitoring program.Complicating matters, farm workers are often reluctant to come forward - even when symptomatic - due to concerns over immigration entanglements or being fired (see EID Journal: Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus among Dairy Cattle, Texas, USA), and farmers remain reluctant to have their herds tested.

Despite a recent decline in H5N1 positive dairy herds, a study published 2 months ago (see Nature: A Mathematical Model of H5N1 Influenza Transmission in US Dairy Cattle), strongly suggests that the H5N1 virus is far more widespread in U.S. dairy cows than has been reported.

We've also seen sharp decline in the number of wildlife H5 detections submitted by the states to the USDA in 2025. How much of this lull is due to an actual reduction in the virus in the wild, and how much is a result of reduced testing, is unknown.

Typically - at least in temperate climes - avian flu activity diminishes sharply during the summer months, but often resurges in the fall when migratory birds resume their annual southbound migration.

While we can never know what the next migration will bring, there is a high likelihood that avian flu activity will resume in the fall, and that new genotypes may accompany that upcoming wave.

Meanwhile, H5Nx continues to spread, and evolve, around the world. Any perceived drop in H5's threat level could easily prove temporary.

Of course, H5N1 isn't guaranteed to spark the next pandemic. It has loomed large several times in the past, only to recede back into the shadows. There may even be an insurmountable `species barrier' that prevents H5 from ever spreading easily in humans (see Are Influenza Pandemic Viruses Members Of An Exclusive Club?).

But HPAI H5 is just one of many respiratory viruses with pandemic potential. Last summer the WHO unveiled an expanded Pathogens Prioritization report, increasing the number of priority pathogens to more than 30.

Additions included 7 different influenza A subtypes (H1, H3, H3, H5, H6, H7, and H10), 5 bacterial strains that cause cholera, plague, dysentery, diarrhea and pneumonia, and several coronavirus contenders.