# 10,321

Yesterday’s announcement of China’s 4th human infection (and 3rd death) from the recently emerged H5N6 virus is just the latest reminder of how diverse the constellation of avian influenza viruses in China has become over the past 3 years.

Although there were plenty of LPAI avian viruses in circulation, prior to early 2013 we really had only one highly pathogenic Avian Influenza virus (HPAI) of concern; H5N1

All of that started to change in the spring of 2013 when we saw the first real contender to the H5N1 virus - H7N9 – appear in China, sparking a mini-epidemic. The virus has now returned three years in a row, and has been diagnosed in more than 640 individuals. The actual incidence of infection is likely many times higher.

A few months later H6N1 showed up in Taiwan, followed a few months after that by the first of several H10N8 infections on the mainland. In January of 2014, H5N8 broke out in wild birds and poultry in Korea, and before the year was out, has spread to Western Europe and to North America.

In April of 2014, yet another HPAI H5 virus emerged, this time an H5N6 virus in a Sichuan China poultry flock, and (fatally) infected one man in Nanchong City.

In short order, this virus was also reported in Vietnamese and Laotian poultry flocks. The EID Journal: Influenza A(H5N6) Virus Reassortant, Southern China, 2014 describes its evolution as: `reassortants of wild duck H5N1 and H6N6 viruses, both of which have pathogenic and potential pandemic capacity in southern China’.

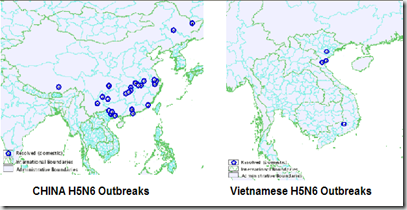

The most recent OIE reports (here, here, & here) show how widespread reports of H5N6 have become in just over a year, likely spread by migratory birds (Hong Kong reported an infected Oriental Magpie-Robin in April of this year).

.

While not as geographically well distributed as its H5N1 and H5N8/H5N2 cousins, H5N6 has nevertheless shown no signs of retreat, and unlike H5N8/H5N2, it has demonstrated an ability not only to infect humans, but to cause serious –even fatal – illness.

While infection and carriage of the virus is to be expected in avian species, another sign of mammalian adaptation comes from a report (h/t and thanks to @RainaMacIntyre for the link) which appeared last month in Nature’s Scientific Reports, called:

Fatal H5N6 Avian Influenza Virus Infection in a Domestic Cat and Wild Birds in China

Zhijun Yu, Xiaolong Gao, Tiecheng Wang, Yanbing Li, Yongcheng Li, Yu Xu, Dong Chu, Heting Sun, Changjiang Wu, Shengnan Li, Haijun Wang, Yuanguo Li, Zhiping Xia, Weishi Lin, Jun Qian, Hualan Chen, Xianzhu Xia & Yuwei Gao

ABSTRACT

H5N6 avian influenza viruses (AIVs) may pose a potential human risk as suggested by the first documented naturally-acquired human H5N6 virus infection in 2014. Here, we report the first cases of fatal H5N6 avian influenza virus (AIV) infection in a domestic cat and wild birds. These cases followed human H5N6 infections in China and preceded an H5N6 outbreak in chickens. The extensive migration routes of wild birds may contribute to the geographic spread of H5N6 AIVs and pose a risk to humans and susceptible domesticated animals, and the H5N6 AIVs may spread from southern China to northern China by wild birds. Additional surveillance is required to better understand the threat of zoonotic transmission of AIVs.

<SNIP>

Sample Collection

During May–June 2014, seventy feces specimens from wild birds and one lung specimen from a dead domestic cat were collected in areas with close-proximity to the residence of the patient infected with H5N6 AIV in Nanchong city, Sichuan province, southwest China. The domestic cat is suspected of having succumbed to AIV infection based on flu-like clinical signs and necropsy findings. Additionally, lung specimens were collected following the sudden and unexplained deaths of three swan geese in Baicheng city, Jilin province, northeast China. No additional information was available. We screened all specimens by RT-PCR for evidence of influenza virus infection.

Virus Isolation

We inoculated the allantoic cavities of 10-day-old specific pathogen-free embryonated chicken eggs with material from the H5N6 AIV-positive lung specimen from the domestic cat and one swan goose. After 60 hours incubation at 37 °C, we recovered two virus isolates, named A/cat/Sichuan/SC18/2014 (H5N6) and A/swan goose/Jilin/JL01/2014 (H5N6).

The infection of a cat by the H5N6 virus isn’t completely unexpected or without precedence, and most likely occurs when a cat eats an infected bird (see Gastrointestinal Bird Flu Infection In Cats).

In 2006, Dr. C.A. Nidom demonstrated that of 500 cats he tested in and around Jakarta, 20% had antibodies for H5N1 the bird flu virus. In 2007 the FAO warned that: Avian influenza in cats should be closely monitored, although so far no sustained H5N1 transmission in cats or from cats to humans has been documented.

In 2012, three domestic cats died in Israel from H5N1 after consuming infected poultry carcasses, and earlier this year Guangxi Zoo Reported 2 Tiger Deaths Due To H5N1.

Last April, in Seroprevalence Of Influenza Viruses In Cats – China we looked at the prevalence of (avian origin) canine H3N2, along with two seasonal human flu viruses, in cats in Northern China.

In a lot of ways, H5N6 seems to be following the same path that it’s venerable uncle – H5N1- blazed a decade ago.

It appears to be spreading rapidly and efficiently via migratory birds, is infecting and killing poultry across a wide swath of Asia, and can (occasionally) jump to humans and produce severe disease. Cats – and potentially other mammals – are also susceptible to infection.

While none of this guarantees that H5N6 will become a major human health threat, the number of new and emerging reassortant avian flu viruses originating from China continues to rise. Just last month we saw H5N9 added to the list (see J. Virol: Emergence Of AN HPAI H5N9 Virus In China).

To this rapidly growing lineage of H5 avian viruses, we can also add the two new H5 variants (H5N2 & North America H5N1) that emerged and spread widely this spring after H5N8 arrived in the Pacific Northwest, and new subtypes of H5N2 and H5N3 that emerged in Taiwan after H5N8 arrived there in December.

Although it is impossible to predict what any of these individual H5 subtypes will end up doing, with so many variations on an H5 theme spreading around the world and mingling with new populations of LPAI viruses, it is a pretty safe bet that we’ll see more reassortants emerge over time.

And with equally unpredictable results.