|

| Credit MOH/CCC |

#11,512

We've been following the outbreak at KKUH (King Khalid University Hospital) in Riyadh for nearly 3 weeks, and what has set this outbreak apart from others we've seen are the number of asymptomatic cases being reported by the Saudis.

While asymptomatic (or perhaps very mild) cases have been reported previously by the Saudi MOH, their incidence was roughly 1 in 10.

Most of those were detected through RT-PCR testing of close contacts of symptomatic patients, although until late last summer, the Saudi MOH didn't appear to be aggressively looking for asymptomatic cases.

This came to a head very publicly last September with the WHO Statement On The 10th Meeting Of the IHR Emergency Committee On MERS, which rebuked the Saudis for their handling of asymptomatic cases (among other issues).

Since then, the Saudis have been far more diligent in seeking out, and reporting, asymptomatic cases. But this does make it difficult to compare rates today to rates reported in previous years.

Still, over the past 20 days the Saudi's have reported 28 cases from the KKUH outbreak, and of those, 21 are listed as being asymptomatic. An unusually high ratio by any standard.

While they don't provide answers, the MOH offers several possible explanations why this may have occurred, including.

- Better and more diligent testing of asymptomatic contacts

- One or more `superspreaders'

- Increased transmissibility of the virus

- Or (optimistically), the virus has lost some of its virulence, resulting in fewer serious infections

While more mild cases sounds like an improvement, this could make the virus harder to contain, and promote greater community spread.

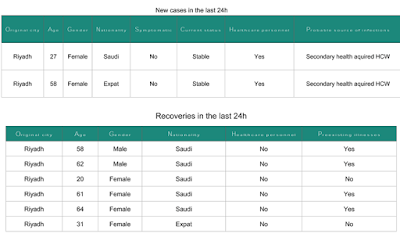

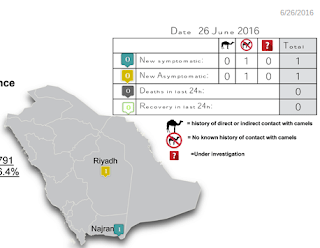

The following comes from the most recent MOH/CCC Weekly monitor report.

MERS Outbreak at KKUH

During the period between 14 and 26 June, 2016 a total of 28 cases of MERS eere reported from King Khalid University Hospital (KKUH), Riyadh. Out of the total cases, 7 (25%) were symptomatic.

There has been a recent increase in reports of asymptomatic or mild MERS-CoV infection. Data from Ministry of Health (MoH) showed that the proportion of asymptomatic infections increased from 10% (2012- July ,2015), to 57% by the end of 2015.

The increased proportion of asymptomatic infections could be attributed to increased number and improved criteria for detection of contacts and/or improved swabbing techniques.

According to MoH guidelines all exposed HCWs should be screened for the virus. It is difficult to rule out presence of a super spreader and increased infectiousness of the virus. The increased proportion of asymptomatic MERS may indicate that the virus has lost some of its virulence.

However, it is hard to estimate the proportion asymptomatic patients among infected individuals because there is no perfect method for defining the exposed contacts. In addition, lack of serological testing could have resulted in missing some other asymptomatic infections.

There was delay in diagnosing the primary case of MERS who happened to be a female admitted for management of a diabetic septic foot. Conceivably, the diagnosis of MERS was least expected.

Nevertheless, the large number of secondary infections within a short period of time in a well-defined health institution points out that there is a clear gap in infection prevention and control in that institution.

|

| Credit MOH/CCC |