#11,928

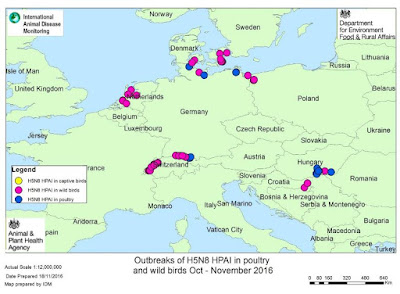

Events are moving quickly on the ground in Europe, and so the map above, and the text below - while published today - we're compiled three days ago, and may not fully depict the H5N8 situation as it stands today.

Still, this report from the UK's DEFRA provides some valuable information, particularly on a genetic analysis of a virus sample recently obtained in Hungary.

While the FAO recently described the H5N8 virus sampled over the summer in Russia as being `readily distinguishable from strains of H5N8 virus found in Europe and North America in 2014-15', the very good news is this latest analysis did not turn up any evidence that the virus has become a greater threat to human health.

The virus, however, is continually evolving and so the threat to humans, while very low, is not zero.

Updated Outbreak Assessment number 3

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N8 in Europe

18th November 2016 Ref: VITT/1200 Avian Influenza in Europe

Disease Report

Reports of H5N8 HPAI in wild birds, poultry and captive birds is still currently limited to eight countries in Europe (Austria, Croatia, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands, Poland and Switzerland) but since our last report on the 11th November, the number of reports has significant increased. There have now been 8 outbreaks in poultry (Hungary, Germany and Austria), one in captive birds (ducks kept in a small zoo in Netherlands) and forty nine reports in wild bird die-offs. The wild bird species include primarily Tufted ducks (Aythya fuligula), common Pochards (Aythya ferina), mute swans (Cygnus olor),and various gulls (Larus sp.) as well as a few other waterbirds, such as grebes, curlews and coots. The situation is moving rapidly, and these number represent the official reports made to the OIE or the EU ADNS system at the time of writing

Situation Assessment

The EURL team has analysed the full genome sequences of several recent H5N8 HPAI viruses with the key focus on the first poultry outbreak in the EU (turkeys in Hungary and grateful to Dr Adam Dan for supply of data). Essentially this virus is representative of the clade in terms of assessing affinity for humans. We have used an algorithm followed previously whereby we check for specified mutations that have been associated with possible increased tropism/virulence for mammalian species including humans (listed via CDC Atlanta website).

The key conclusion is that these viruses to date are still essentially bird viruses without any specific increased affinity for humans.

PHE (2016) have issued updated advice that this latest series of outbreaks and wildbird cases does not significantly increase the risk to public health:

- The risk of avian influenza A(H5N8) infection to UK residents in the UK is very low.

- The risk of avian influenza A(H5N8) infection to UK residents who are travelling to countries currently affected is very low.

Conclusion

This risk to the UK is MEDIUM for any incursion of H5N8 HPAI in wild birds. The migration season will generally peak at around December to January when our migratory birds will be present at wintering sites in the UK, but these birds are already arriving and have been for several weeks. The risk to poultry depends upon the level of biosecurity implemented on farm to prevent the direct or indirect contact with wild birds. It should be noted that the virus could potentially survive on pasture in wild bird faeces for several weeks at current ambient temperatures emphasising importance of these measures.

Poultry keepers and veterinarians should remind themselves of the clinical signs caused by avian influenza viruses (see Irvine, 2013, for more details).

Any wild bird die-offs can be reported via the Defra helpline at defra.helpline@defra.gsi.gov.uk

We would like to remind all poultry keepers to maintain high standards of biosecurity, remain vigilant and report any suspect clinical signs promptly. Poultry keepers should also remind themselves of the mild clinical signs of LPAI infection and be aware of any changes in egg production, feed and water intake or rise in mortality above baseline. Whilst clinical signs in chickens and turkeys with HPAI can be very marked with often rapid onset they may initially manifest as reductions in feed or water intake (>5%). Furthermore clinical signs in domestic waterfowl for this current strain of virus are less certain and may present as a wide spectrum with variable mortality.

We will continue to report on the situation