#12,357

Eastern China has long had the reputation of being the `cradle of influenza' (see Viral Reassortants: Rocking The Cradle Of Influenza), being the birthplace of H5N1 in the mid 1990s, SARS (admittedly a coronavirus, not influenza) in the early 2000's, and the strong suspicion that 2 of the 3 major influenza pandemics of the last century (1957's Asian Flu, 1968's Hong Kong Flu) originated from that region.

In recent years, the number of novel flu viruses coming out of China has only accelerated, with H7N9 emerging in 2013 - followed by H10N8 - both of which have infected and killed humans. In 2014, two more avian flu viruses - H5N6 and H5N8 - emerged, and both can be traced back to China.

Each of these subtypes has spun off multiple clades, strains, or lineages - and these are just the major players. China's poultry, and wild bird populations are hosts to dozens of other influenza A subtypes (H9N2, H6N1, H6N6, H4N1, etc.) providing abundant genetic building blocks for generating new subtypes.

When you add human and swine influenza viruses to the mix, live markets with many different types of birds grouped together, and ample opportunities for humans and livestock to interact - you've got the essential ingredients for brewing zoonotic diseases.

Just two weeks before we first learned about the newly emerging H7N9 virus in the spring of 2013 a study (see EID Journal: Predicting Hotspots for Influenza Virus Reassortment) identified 6 key geographic regions where reassortments are likely to emerge.

And high on that list (you guessed it), was Eastern mainland China.

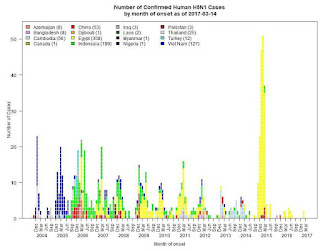

Between this winter's unprecedented H7N9 epidemic and the jump of H5N6 from China to Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, there's little wonder that China's neighbors are worried that they may be next.

Two weeks ago, in FAO: Reinforcing Control Efforts Against H7N9 In China, in response to both the increased rate of infection, and the emergence of an HPAI H7N9 strain, the FAO warned:

Neighbouring countries remain at high risk, and all those that have poultry trade connections - either formal or informal - to China. A further concern is the possibility that changes seen in the H7N9 virus may affect wild bird population, posing risks to their health or turn them into migratory carriers of the virus, expanding the risk of the virus spreading further as has been seen with other avian influenza strains in faraway Europe, Africa or the Americas.Over the past month we've seen repeated dire warnings from the Vietnamese government over that country's vulnerability to H7N9 (see Vietnam Girds Against H7N9).

Today, it seems to be Russia's turn to fret, with media warnings that avian H5N6 may be winging its way out of China and into Russian territory with this spring's migration.

The headline `России грозит опасный для человека птичий грипп' - `Russia is in danger to human bird flu' - or variants thereof, have appeared on dozens of Russian websites in the past few hours.

Typical of these reports is the following from dp.ru, which contains a statement from Nikolai Vlasov, the Deputy Head of Rosselkhoznadzor Russia's Federal Service for Veterinary and Phytosanitary Surveillance.

The authorities have warned of the possibility of visiting Russia for the deadly bird flu humanAs Vlasov points out, while the export of H5N6 into Russia isn't guaranteed, a look at the migratory flyways of East and Central Asia (see below) provide plenty of reasons for concern.

In Russia, you may receive the avian flu, which is very dangerous to humans. It originated in Southeast Asia, several people have died from it.

Deputy Head of Rosselkhoznadzor Nikolai Vlasov said that Russia may appear dangerous to the human strain of bird flu. First of all at-risk group includes areas of the Far East, he said, reports RBC .

Vlasov also said that the virus originated in Southeast Asia, several people have died from it. "This bird flu virus was born in Southeast Asia, and already have the first fatalities from the virus it threatens our Far Eastern District, if the drift of influenza virus will be, it is not predetermined, but highly probable.", - said Vlasov.

The official stressed that due to the current threat is necessary to be extremely careful.

As explained in the press-service agency, we are talking about the danger of getting H5N6 strain. According to Vlasov, now operates three avian influenza virus in the world.

And while H5N6's recent incursions in to Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan suggest it may be the more mobile of the two, the recent emergence (and spread) of HPAI H7N9 has to be on their minds as well.

As southbound migrations have historically sparked more avian flu outbreaks than northbound, perhaps the bigger concern is; what comes back next fall after these novel, and highly promiscuous, viruses have spent the summer in the world's high latitude nesting areas?

While it's not actually a Chinese curse, we do seem to live in `interesting times'.