#13,560

We've a new EID Journal Dispatch that reminds us of the limits of infectious disease surveillance, and that our initial perception of an infectious disease threat can change over time.

In December of 2013, a mosquito-borne virus called Chikungunya arrived in the Americas for the first time (see CDC Update On Chikungunya In The Caribbean), presumably imported by international travelers who visited while viremic, and inadvertently introduced the virus to the local mosquito population.While reportedly rarely fatal, the CDC described the symptoms of infection as lasting a few days to a few weeks, producing `debilitating illness, most often characterized by fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, muscle pain, rash, and joint pain’, although some may experience `incapacitating joint pain, or arthritis which may last for weeks or months.’

Up until the middle of the last decade, Chikungunya had been a seldom seen mosquito-borne virus, pretty much limited to central and eastern Africa. All of that changed in 2005 when it jumped to Reunion Island in the Indian Ocean, where it reportedly infected about 1/3rd of that island’s population (266,000 case out of pop.770,000) in a matter of a few months.

From there, apparently aided and abetted by a recent mutation that allowed it to be carried by the Aedes Albopictus `Asian tiger’ mosquito (see A Single Mutation in Chikungunya Virus Affects Vector Specificity and Epidemic Potential), it quickly cut a swath across the Indian ocean and into the Pacific.

With competent mosquito vectors and a chikungunya naive population, this mosquito-borne virus spread quickly across the Caribbean islands, South America, and by the following summer, even into Florida (see CDC Statement On 1st Locally Acquired Chikungunya In United States).

Puerto Rico saw a significant Chikungunya epidemic in 2014-15 (see EID Journal High Incidence of Chikungunya Virus and Frequency of Viremic Blood Donations during Epidemic, Puerto Rico, USA, 2014), but the virus never really established itself in the lower 48 states.

Today's EID Journal Dispatch takes a look back at the 2014-2015 epidemic in Puerto Rico, and compares the number of excess deaths during that period to the previous four years, and finds evidence to suggest the number of deaths from the virus may have greatly exceeded the 31 that were officially reported.I've only included some excerpts from a much longer, detailed, report. Follow the link to read it in its entirety. I'll have a postscript when you return.

Volume 24, Number 12—December 2018

Dispatch

Excess Mortality and Causes Associated with Chikungunya, Puerto Rico, 2014–2015

André Ricardo Ribas Freitas, Maria Rita Donalisio, and Pedro María Alarcón-Elbal

Abstract

During 2014–2015, a total of 31 deaths were associated with the first chikungunya epidemic in Puerto Rico. We analyzed excess mortality from various causes for the same months during the previous 4 years and detected 1,310 deaths possibly attributable to chikungunya. Our findings raise important questions about increased mortality rates associated with chikungunya.

In December 2013, the first locally acquired chikungunya virus infections in the Americas were reported in Saint Martin. Since that report, the virus has spread to 45 countries and territories in North, Central, and South America, causing ≈2.4 million suspected and confirmed cases and 440 deaths through December 2016 (1).

Chikungunya has emerged worldwide since 2004. Several gaps in knowledge exist about the disease and its consequences. Until recently chikungunya was considered a nonlethal disease, but severe forms and deaths have been described since an epidemic on Réunion Island during 2005–2006 (2).

In Puerto Rico, the chikungunya epidemic began in May 2014 as the first occurrence of the virus in the country (3). Official surveillance reported 28,327 suspected chikungunya cases, of which 4,339 were laboratory-confirmed; 31 persons died (0.9 deaths/100,000 population).

The chikungunya mortality rate was significantly lower than that observed in epidemics on other islands, such as Réunion Island (25.9 deaths/100,000 population in 2006), Martinique (20.5/100,000 population in 2014), and Guadalupe (14.4/100,000 population in 2014) (1,4). These differences could be a consequence of the difficulty of recognizing the etiology of severe clinical forms and deaths.

(SNIP)

Conclusions

We found substantial excess mortality in Puerto Rico during the 2014 chikungunya epidemic, which should no longer be treated as a nonlethal disease. In addition to elderly persons, excess deaths occurred in other age groups. The main causes of death in patients with laboratory-confirmed chikungunya in hospital-based studies were similar to those in our study (2,13).

Our study reinforces the hypothesis of the association of chikungunya with severe manifestations and deaths. Chikungunya-related death is critical to defining public health priorities, such as investment in research, vaccine development, and vector control. The evaluation of excess deaths is a tool that should be included in the assessment of chikungunya epidemics.

The results of our study are subject to several limitations. We conducted an ecologic analysis, which does not enable establishment of causality, and the investigation was based on secondary data, which may result in some inaccuracies. Therefore, some of the excess deaths we calculated might have resulted from other diseases, particularly vectorborne diseases, which have seasonal patterns of occurrence similar to that of chikungunya.

However, we tried to reduce these limitations using several sources of information and accounting for other diseases that could interfere in the deaths in the region, including other viral diseases. The method used in this study is already well known and widely used to estimate deaths and hospitalizations associated with respiratory viruses and extreme weather phenomena (14,15).

Although limited, our results raise important questions about the occurrence of severe disease and increased mortality rates associated with chikungunya. Therefore, fundamental research is needed about chikungunya pathophysiologic mechanisms involving severe forms, exacerbation of preexisting conditions, and deaths. In addition to clinical studies, systematic diagnostic research of recent infection, including chikungunya, in all severe hospitalized patients during outbreaks could answer some important questions.

Dr. Freitas is a medical epidemiologist who works in the epidemiologic surveillance of Campinas, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil, and is a professor of epidemiology, biostatistics, and scientific methodology at Faculdade de Medicina São Leopoldo Mandic de Campinas. His primary research interests include studies of mortality and communicable diseases, with emphasis on arboviruses and respiratory viruses.

It should be noted that all of these excess deaths cannot be directly linked to the arrival of the Chikungunya virus, just as all of the excess winter mortality reported each year around the world cannot be completely attributed to influenza.

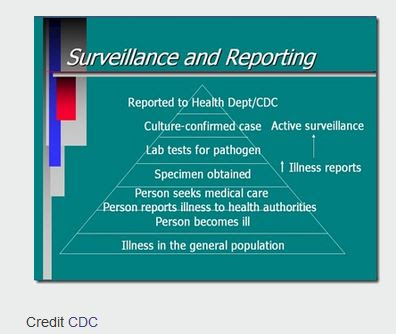

There is certainly a correlation, but other factors (or viruses) may be at work.In truth is we never really know how many people are infected, or killed each year, by infectious diseases - even in the most developed nations of the world (see CDC chart at top of this blog).

Six months after our horrific 2017-18 flu season, we are still only seeing estimates of its impact (see CDC: More Than 900,000 Hospitalizations & 80,000 Deaths In Last Winter's Flu Season) - and while these numbers may be revised and refined - the exact numbers will never be known.Heart attacks and strokes can easily mask the underlying cause of death (see Eur. Resp.J.: Influenza & Pneumonia Infections Increase Risk Of Heart Attack and Stroke) - as can preexisting conditions and co-morbidities.

Contrary to what people see on TV, people who die unexpectedly from non-violent causes are rarely subjected to a battery of tests, or an autopsy. Often the cause of death listed on the death certificate is - at best - an assumption based on the individuals medical history.While not definitive in its conclusions, today's study finds a pattern of excess mortality that coincides with the arrival of Chikungunya in Puerto Rico that needs further exploration.

And it also reminds us that when we see reports stating that X number of people were infected by (or died from) MERS-CoV, Avian Flu, or Ebola somewhere in the world - we really should assume that these just represent the tip of the pyramid.