Photo Credit Wikipedia

#14,039

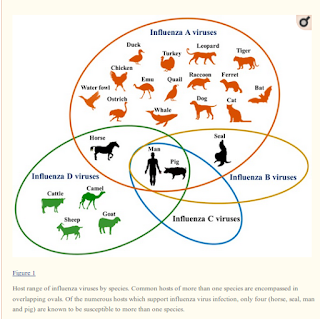

Among flu viruses - influenza A & B - due to their high burden of disease in humans and (influenza A's, in particular) wide host range - are the primary focus of influenza research.

But in recent years, attention is increasingly being paid to two other, lesser known, flu types; Influenza C & D.Influenza C infections are generally associated with mild respiratory illness, and are not thought to pose a pandemic threat.

Last February, however, we looked a a study in the EID Journal (see Detection of Influenza C Virus Infection Among Hospitalized Patients, Cameroon), which called for improved surveillance and research, after detailing 3 serious Influenza C infections detected in children in Africa.

Since the 1940s the influenza universe was thought to contain only three types (A, B & C), but a 4th influenza type (D) was identified - via a circuitous route - in 2011.We first learned of this new flu early in 2013 when researchers reported finding a novel influenza virus in swine from Oklahoma - initially classified as a novel Influenza C virus - but which would later be designated as Influenza D.

Their research – published PLoS Pathogens – was called Isolation of a Novel Swine Influenza Virus from Oklahoma in 2011 Which Is Distantly Related to Human Influenza C Viruses, and it immediately caused a stir in the flu research community.

The authors found that this new (provisional) influenza C virus could infect, and transmit, in both ferrets and pigs.The following year, in mBio: Characterizing A Novel Influenza C Virus In Bovines & Swine, cattle were added to the list, and now appears to be the virus's primary reservoir.

Although it isn't known if Influenza D can cause symptomatic illness in humans, in the summer of 2016 - in Serological Evidence Of Influenza D Among Persons With & Without Cattle Exposure - researchers reported finding a high prevalence of antibodies against Influenza D among people with cattle exposure.

|

| Credit Novel Flu Viruses in Bats and Cattle: “Pushing the Envelope” of Influenza Infection

|

Influenza D has yet to prove itself to pose a public health threat, but it is worth noting that only 4 species - humans, horses, pigs, and seals - are known to be infected by more than one influenza type (A, B, C or D), and of those only 2 - humans and pigs - are believed susceptible to all four.

We covered this history in a bit more depth about 3 months ago in J. Clinical Med. : A Review Of The Emerging Influenza D Virus.Over the past week a couple of new Influenza D related items have appeared in the Journals, each of which adds to our growing knowledge of this recently identified flu type.

First, from the EID Journal, more evidence that Camels may be important carriers of the virus.

ABSTRACTResearch LetterInfluenza D Virus Infection in Dromedary Camels, Ethiopia

Shin Murakami, Tomoha Odagiri, Simenew Keskes Melaku, Boldbaatar Bazartseren, Hiroho Ishida, Akiko Takenaka-Uema, Yasushi Muraki, Hiroshi Sentsui, and Taisuke Horimoto

Influenza D virus has been found to cause respiratory diseases in livestock. We surveyed healthy dromedary camels in Ethiopia and found a high seroprevalence for this virus, in contrast to animals co-existing with the camels. Our observation implies that dromedary camels may play an important role in the circulation of influenza D virus.

Influenza D virus (IDV) was first isolated from pigs with respiratory symptoms in the USA in 2011 (1). Epidemiologic analyses revealed that the most likely main host of IDV is cattle, because the seropositivity rate in these animals is higher than that for other livestock (2–4).

In a recent report, dromedary camels (Camelus dromedaries) exhibited substantially high seroprevalence (99%) for IDV in Kenya (5), suggesting that this animal is a potential reservoir of IDV. We examined seroprevalence of IDV in dromedary camels in Ethiopia and in Bactrian camels (Camelus bactrianus) in Mongolia.(SNIP)

In a previous report, a considerable number of dromedary camels in Kenya were seropositive not only for influenza D but also for influenza C virus (ICV) (5). Thus, we additionally used C/Ann Arbor/1/1950 virus as an antigen for HI assay. The results suggest a limited circulation of ICV in this area because 0 samples in Bati were positive and only 2 in Fafen, which were negative for IDV, were positive (titers 1:40). In addition, we performed the HI test using selected samples following preadsorption with ICV. We did not observe any significant decrease in HI titers to IDV, suggesting no cross-reactivity between IDV and ICV in our samples.

We also collected serum samples of apparently healthy Bactrian camels (n = 40) in Dundgovi, Zavkhan, and Umnugovi Provinces, Mongolia, and tested for HI antibody for IDV. These samples did not test positive for these IDV strains.

Despite the limited samples tested, this study suggests that dromedary camels in East Africa might play a substantial role in the circulation of IDV. Further studies using additional samples from multiple countries are expected to clarify the role of this animal on the ecology and epidemiology of this virus, including its reservoir potential in nature.

The second report comes from the Journal Viruses, and it deals with human cellular tropism, replication, and the development of antibodies to Influenza D. This is a lengthy and detailed (open-access) article, and I've only included a few excerpts.Dr. Murakami is an associate professor at the Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan. His research interests include epidemiological and molecular biological studies of animal viruses, including influenza viruses.

Follow the link to read it in its entirety.

Determining the Replication Kinetics and Cellular Tropism of Influenza D Virus on Primary Well-Differentiated Human Airway Epithelial Cells

Melle Holwerda 1,2,3,4, Jenna Kelly 1,2,3,†, Laura Laloli 1,2,3,4,†, Isabel Stürmer 1,2,3,4,†, Jasmine Portmann 1,2,3, Hanspeter Stalder 1,2,3 and Ronald Dijkman 1,2,3,*

Received: 10 April 2019 / Accepted: 22 April 2019 / Published: 24 April 2019

Abstract

Influenza viruses are notorious pathogens that frequently cross the species barrier with often severe consequences for both animal and human health. In 2011, a novel member of the Orthomyxoviridae family, Influenza D virus (IDV), was identified in the respiratory tract of swine.

Epidemiological surveys revealed that IDV is distributed worldwide among livestock and that IDV-directed antibodies are detected in humans with occupational exposure to livestock.

To identify the transmission capability of IDV to humans, we determined the viral replication kinetics and cell tropism using an in vitro respiratory epithelium model of humans. The inoculation of IDV revealed efficient replication kinetics and apical progeny virus release at different body temperatures.

Intriguingly, the replication characteristics of IDV revealed higher replication kinetics compared to Influenza C virus, despite sharing the cell tropism preference for ciliated cells. Collectively, these results might indicate why IDV-directed antibodies are detected among humans with occupational exposure to livestock.

(SNIP)

There are several indicators that IDV has a zoonotic potential. For instance, the utilization of the 9-O-acetyl-N-acetylneuraminic acid as a receptor determinant, that allows the hemagglutinin esterase fusion (HEF) glycoprotein of IDV to bind the luminal surface of the human respiratory epithelium [16]. Interestingly, the utilization of this receptor is also described for the closely related Influenza C virus (ICV) [17].

Furthermore, the detection of IDV-directed antibodies among humans with occupational exposure to livestock and the molecular detection of IDV in a nasopharyngeal wash of a field worker with close contact to livestock indicates that cross species transmission occurs [15,18]. However, thus far, there is no indication of wide spread prevalence among the general population although the virus has been detected during molecular surveillance of aerosols collected at an international airport [19,20]. Therefore, it remains unclear whether IDV can indeed infect cells within the human respiratory tract and, thus, whether it has a zoonotic potential.

(SNIP)

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that IDV replicates efficiently in an in vitro surrogate model of the in vivo respiratory epithelium at ambient temperatures that correspond to the human upper and lower respiratory tract. We also demonstrate that IDV viral progeny is replication competent, as it can be efficiently sequentially propagated onto well-differentiated hAEC cultures from different donors at both 33 °C and 37 °C.

This seems to occur without extensive adaptation to the human host, as only a single non-synonymous mutation in the coding sequence of the HEF gene segment was identified among multiple samples. Intriguingly, the replication characteristics of IDV revealed much higher replication kinetics compared to Influenza C virus, despite sharing the cell tropism preference for ciliated cells. These results show that there is no intrinsic impairment for IDV propagation within the human respiratory epithelium.(Continue . . . )

For now there is little indication that influenza D poses a serious human health threat. Human illness, assuming it occurs with IDV infection, appears to be mild.

Viral evolution, however, prevents us from assuming this will always hold true.The more we learn about it now, the better we'll be able to deal with it should it ever become a public health threat.